In the film The Belly of an Architect, Stourley Kracklite sends a postcard to a fellow architect from the 17th century, Étienne-Louis Boullée: “Monsieur Boullée, I hope you don’t mind me writing to you like this. I feel I know you well enough to talk to you.” It comes as no surprise that the main character in the Peter Greenaway film feels a closer bond to a dead idol than his own contemporaries. “I prefer to speak to the dead” Lech Majewski insists in interviews promoting The Mill and the Cross, as if subscribing to Kracklite’s mailing list. As opposed to the characters in Greenaway’s film, the director employs technology to enter into a dialog with the historic master. The digital signature almost seems to read: “Dear Mr. Bruegel…”

Those who recall the 1956 biopic Lust for Life, which tells the story of Vincent Van Gogh, might be surprised just how much this film genre has evolved since then. Vincente Minnelli’s modernist project would not have worked as well today, as proven by the recent release of Raoul Ruiz’s Klimt, based on a similar concept. These exploration have passed the stage in which the artist’s biography is illustrated with their work (Frida, Pollock), and have now boldly stepped into the realm of “meta” (Nightwatching and The Mill and the Cross), where it is the artist who is described by his opus magnum. The richly allegorical story of Peter Breugel the Elder’s painting comes to life, in part as an analysis conducted by an art historian (the script was largely based on an exhaustive book by Michael Francis Gibson), and in part as a fantasy about a “frozen” scene. In The Mill and the Cross, the scene is arranged into a story conceived by Majewski.

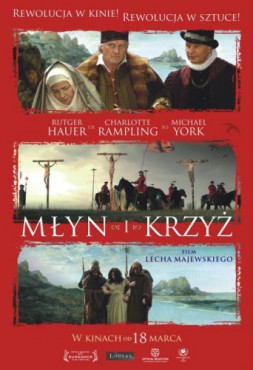

The Mill and the Cross, dir. Lech Majewski.

The Mill and the Cross, dir. Lech Majewski.

Poland / Sweden 2010,

in cinemas from 18 March 2011

16th century Holland is a time of cruel persecution conducted by the Spaniards. The backdrop of the film consists of an “autointerpretation” of the The Way to Calvary and the motif of Stabat Mater Dolorosa, adapted to the period. Bruegel makes sketches in preparation for the painting, strolling around a landscape featuring a mill perched on a solitary rock. His patron laments the state of the country. The suffering of Christ is hidden somewhere in this narration. Majewski and Gibson tell the individual stories hidden in the painting, explaining them through the mouth of Bruegel himself, as in the scene where the painter explores the metaphor of the circles. On the left we have the city walls, a circle of life, and on the right there is a crowd of gawkers huddled in a circle, waiting for the crucifixion. The final word belongs to a final circle — facing the hardship of life at work (the miller) and in play (the dance with which the film culminates).

The Mill and the Cross has probably broken the record for time spent in post-production. Two years have passed since filming wrapped up in 2009. The scenes were shot on a blue screen due to the green color dominant in Bruegel’s The Way to Calvary. The characters in the finished product are just one of the many layers involved. Others included painting the background (by hand, with some parts “copied” off the painting), landscapes, shadows, as well as the sky, shot in New Zealand for a perfect match with the Dutch canvas. The landscape shots were done in Silesia and the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland. The story resembles the filming of The Gospel According to Harry, during which Majewski tried long and hard to capture the “essence” of the American desert, which he finally shot in Poland. A minor technological miracle was provided by the Red One digital camera (manned by Adam Sikora), hitherto employed largely on the sets of Oscar nominated productions and action films (The Social Network, In a Better World, Pirates of the Caribbean 4). The resolution and depth of field offered by the camera enabled the filmmaker to achieve quality equal to 35mm tape, but with the option to edit the footage almost down to the photon level. Compared to typical blockbuster movies, Majewski’s film was definitely a demanding test of the Red camera. Even the most distant backgrounds are perfectly sharp, in keeping with Bruegel’s intentions, while the crucifixion of Christ is in fact lost in the crowd, dominated by the mill built on the rock.

Digital technology is more than just a boon to masterful filmmakers with an interest in painting. It is a tool that allows us to re-analyze pieces about which we thought everything had been written. One example is Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. In 2007, Pascale Cotte photographed the painting using a camera of his own design, at a resolution of 240 million pixels and using filters of varying colors to reveal previous versions of the painting. He thus succeeded in exposing several false interpretations and legends that had been passed down from generation to generation. Cotte’s photographs depict a closing of the lips and changes in the texture of the paint. Majewski conducts a similar “enlargement” of the characters in the painting, zooming in on the smooth cheek of Jonghelinck (played by Michael York) or the furrowed chin of Bruegel (Rutger Hauer) — all to extract the “living juice” that had gone dry after centuries under a layer of varnish, and to confirm that the concept of the “close-up” (both in the sense of “zooming in” and a close reading) is a perfect tool for interpreting a work of art.

This film is Lech Majewski’s third approach to the topic of paintings. In interviews, the director often recalls that the astute depiction of the concept behind Giorgione’s The Tempest in Antonioni’s Blowup was the sole reason for his choosing to go to film school. While living in New York in the 90s, Majewski made a biopic about Jean-Michel Basquiat along with Julian Schnabel. Due to pressure from the producers, the final result was significantly different from Majewski’s original script. The film ended up as a clichéd portrait depicting Basquiat — like Kirk Douglas in Lust for Life — as an artist tormented by his weakness for drugs, if not by mental illness. The Garden of Earthly Delights, meanwhile, can be characterized as The Belly of an Architect with a bit more heart. The painting by Hieronymus Bosch serves a function similar to that of the work by Étienne-Louis Boullée — it is an artwork, immortalized by history, that serves as a backdrop for the dramatic portrayal of a disease. As opposed to Greenaway, Majewski mourns his character. This third attempt brings the painting to life, turning its history, composition, and allegories into cinematic reality. In The Garden of Earthly Delights, the characters staged fragments of the painting, thus making life imitate art. The Mill and the Cross elevates that “grainy realism” to HD quality and mixes it with painted mystification. Instead of overwhelming the viewer, the film leaves us space — space perhaps reserved for Dutch audiences.

“Here, the heart of my web, which I shall spin like a spider.” The film’s Bruegel traces converging lines in his sketchpad. The web of equivalent ties immortalized in The Way to Calvary is recreated by the director with the use of different media. In Majewski’s view, Bruegel’s painting is a collection of “broken perspectives”. The spaces in the canvas convey the stories of the figures in the painting. On Bruegel’s cue, time stops in the film. We pick out the Savior in the crowd, but we don’t see his face. Majewski reminds us that most of the great events in history were overlooked by contemporaries. Innovative and artistically bewildering, The Mill and the Cross is a definite pièce de résistance for any museum or art gallery. But on movie screens, the film might suffer the fate of Bruegel’s Icarus, even alongside other Red camera productions. Let’s hope I’m wrong. It is, after all, one of the best postcards ever sent back to a dead artist.

translated by Arthur Barys