It starts out intense, with a close-up of an engraving by Albrecht Dürer, in which Cain murders Abel. Then comes life. Water appears, and in that water, murky and rough, one man is drowning, while another comes to his rescue, pulling him out onto the shore and performing mouth to mouth. Another place at another time: the same man who had just demonstrated his knowledge of CPR is running along railroad tracks, dashing in between trains. Someone is chasing him, and he is finally caught. It’s the police. A dog snarls, tempers flare. One kick, then another, and he falls to the ground. They throw him in squad car and take him to jail. Cut. The film finally starts in earnest.

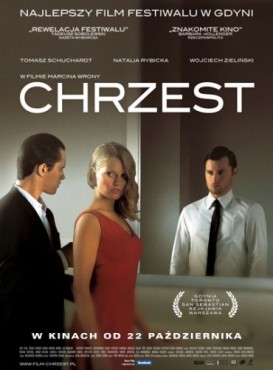

Chrzest, dir. Marcin Wrona.

Chrzest, dir. Marcin Wrona.

Poland 2010, in cinemas from 22 October 2010Several years have past. The rescued, one man by the name of Janek, comes home after completing his military service and makes a beeline to his rescuer, Michał. Michał lives in a bright home with tall windows, but he’s not home. Janek has two bottles of vodka with him, but no harm – they’ll have more than enough time to drink them. He is greeted at the door by his friend’s wife, who invites him in and offers him a bowl of soup in the kitchen. A baby cries in the other room, a large dog lies sprawled in the corner. This is the scene. What happens next can be predicted by anyone who remembers Marcin Wrona’s last film, My Flesh My Blood. This is how goes: the husband comes home, the friends exchange hugs, break out the vodka, perform a Polish rendition of the New Zealand rugby team’s Haka dance, and go out on the patio. Before them stretches a strange and majestic city. They start talking, getting right down to the serious stuff. No small talk. The fundamental question is quickly asked: what do you want out of life? Michał talks about settling down, Janek says he wants to get involved with the crew of Gruby, a certain Warsaw gangster for whom Michał once worked. The rehabilitated criminal advises him against it, offering him something else: his wife and kid. He knows the end is near; having once double-crossed Gruby’s crew, he now has to pay, first with money, and when that runs out – with his own head. What does the wife think of the arrangement? No one asks.

Marcin Wrona suffered severe criticism for My Flesh My Blood. This time, in an attempt to stay one step ahead of the critics, the director has chosen to interpret himself. He has explained in interviews that he is no chauvinist and has no problem with women, although the same might not be true of his characters. He goes on to say that his films have been criticized by ruthless critics, cold rationalists who – in their obsession with some critical theory – have lost the ability to enjoy films any way but cerebrally. The director openly admits to having once suffered from the same affliction, but has since understood that if he were ever to write about film again, he would watch with his heart and write with his emotions.

The above words can be regarded as a kind of confirmation of the claim that auto-referentiality is one of those things that pose the greatest challenge to contemporary man. If Wrona hadn’t jumped the gun on his critics, I could not claim that he is tilting at thin air and has lost touch with realty. After all, no one accused the boxer from My Flesh My Blood of being a chauvinist. That’s not what it was about. What was chauvinistic about the film was the camera itself, the way it leered at women and how it arranged them, making objects or whores out of them, as needs warranted.

The same is true of The Christening. Who cares about two hot-tempered guys playing catch with one of their wives. Who cares if all they see in her is an “untouchable and holy” woman. The point is that the camera is equally incapable of perceiving anything more in her. In the sunny, majestic, pure shots, Michał’s wife Magda almost appears as an immaculately conceived virgin, a deity to be believed in and loved as it is done in Poland: out of habit, thoughtlessly, selfishly. As far as emotions go, I can’t say that The Christening failed to evoke any feelings in me, but neither did it leave me paralyzed with emotion, unable to pose questions such as the ones above. If films are to be interpreted through emotions, does it follow that they should be made with emotions as well? What are we to make of the numerous cultural tropes and symbols littered throughout Marcin Wrona’s latest film? Water, Cain, Abel, Dürer – are we to take these as nothing more than the artist’s emotions? I see it as a calculated choice intended to cloud what is actually missing in Wrona’s simplistic tale of two thieves, anglers, and criminals. Michał and Janek are no sons of Adam and Eve, they are merely the progeny of American gangster flicks, adopted by Polish cinema.

Setting aside all the shortcomings of Wrona’s latest film – an overblown, dishonest movie stuck in a trivial portrayal of femininity and masculinity, an embodiment of what my neighbor once described when prompted to picture an ideal world (“I’m out on a bench, a cigarette in one hand, a beer in the other, a chick between my legs, with friends all around”) – I have to admit honestly that it’s getting better. The creator of My Flesh My Blood does a better job of keeping this story under control, forgoing visual gimmicks and directing the actors with greater confidence.

But what’s most interesting is what we find in the margins. The Christening, perhaps unintentionally, reveals an astounding lack of vocabulary. Their gestures and phrases used by Wrona’s characters are hackneyed, pathetic, and insufficient. Janek and Michał live with this paranoid conviction that unless they keep repeating lines from Goodfellas and other Hollywood gangster films, they will be nobodies. They are paralyzed and unable to find another language with which to communicate with the world, a tongue that would enable them to articulate their own truths. They are lonely because they can only be understood by the likes of Robert DeNiro. They’re losers because they know that the truth of Robert DeNiro will never be their truth.

translated by Arthur Barys