Boguś tattooed the words “Fuck Off” on his forehead and roams the city trashing cars, just to stick it to the world. He scouts out allies in between rampages, but all anyone does is roll their eyes and offer a bit of sound advice: “Why don’t you get a job instead?” But Boguś has no intention of listening to anyone, even when a former teacher recites poems by Osip Mandelstam to him. He gets what’s coming to him: a couple of local gangsters whose car he destroyed catch up with him and give him one day to cough up 20,000 to cover the damages. He thinks nothing of it, and chooses to pick on a wheelchair-bound invalid and hit on a girl working at an abattoir instead of coming up with the cash. We follow Boguś and his adventures, shot on black and white film with an underground aesthetic (obviously), interspersed with animated sequences in revolutionary colors by Krzysztof Ostrowski. It was supposed to be loud, furious, iconoclastic and hard, but instead it’s just pathetic.

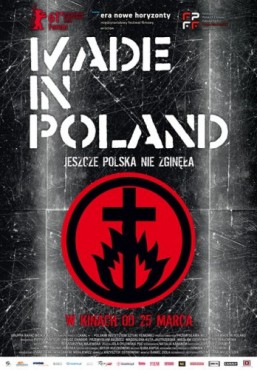

Made in Poland,

Made in Poland,

dir. Przemysław Wojcieszek,

Poland 2010, in cinemas from 25 March 2011It’s not that Boguś’s exploits are insufficiently spectacular, but why does he do it in the fist place? Has he been reading Bakunin, joined a cult, or started attending lectures by a former revolutionary? Or has he been chosen by God? Who knows. All the film tells us is that Boguś isn’t much of a churchgoer. Aside from that, he’s not a bad boy. He might be from the ‘hood, but he used to be an altar boy, attended vocational school, and is the son of a woman whose entire world is the Polish crooner Krzysztof Krawczyk. His imagination has been shaped by TV, he doesn’t care for “fags”, neither does he enjoy American music. He dresses like a skinhead, but he’s probably not a fascist. He behaves like an imbecile, yet has the mental capacity to find a rhyme for “love”. He isn’t good with girls, and has probably never had one, but he has a way of falling in love at first sight. Who or what has pushed him into the embrace of destruction? Where did this freak come from? Are we still in Poland or is this Mars? Wojcieszek has chosen to keep mum and refuses to tell us. That’s obviously a convenient strategy, but hardly one on which to base a critical analysis of a depraved system. A manifesto would be even harder: how does one even begin to demand change when we don’t even know what’s wrong?

The structure of the film is supposedly circular, which would lead us to believe that it is informed by a melancholy awareness; the author realizes that a revolution has no chance of succeeding in today’s world, that there’s no hope for change, yet the atmosphere the whole film projects tells us otherwise. No doubts, no turning back, no despair, no painful void. There is an astonishing certainty to Wojcieszek’s work. You can tell he knows everything and has gotten to the bottom of it all, enabling him to work it all out. He has a sweeping generalization for everything, from the Church to apartment-dwellers. Hamburgers are disgusting, money is dirty, supermarkets are dishonest, and Saturday afternoon barbecues are just plain wrong. Toss in jokes about church ladies, Polish bigotry, and Father Rydzyk while you’re at it. I appreciate the shrewdness, but what exactly is wrong with barbecues? I have no idea what Wojcieszek is on about. Does it bother him that people watch too much TV? Or that the faith of Poles is largely superficial? That their patriotism is just for show? That people’s minds are being clouded by the media? That we need to put an end to post-politics, neoliberalism, and imperialism? The subjects are all worthy of newspapers, and just about as intelligent. Superficial diagnoses and silly complaints.

While watching Made in Poland, I began to wonder what the film would have been like if the main character had a different word tattooed on his forehead, such as “beetle” or “deer”. Maybe the animals would succeed in popping this pretentious balloon, this puppet theatre pretending to be punk rock.

As I watched this hodge-podge of characters, supposedly crazy and yet so unoriginal – a boy with “Fuck Off” tattooed on his head, a girl from an abattoir, a priest who was born again in Rwanda, a gangster endlessly going on about Krzysztof Krawczyk – all I saw was paper: paper rage, paper emotions. Wojcieszek has nothing interesting to say about their world. He merely puts ridiculous, anti-systemic slogans in Boguś’s mouth, hoping that no one will figure out that they are little more than the director’s own sentiments. Sure, we’ve got “bottles with gasoline” and “punk’s not dead”, but it’s time to grow up or at least evolve.