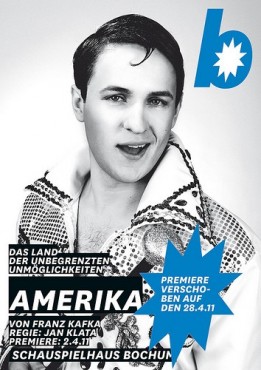

Bochum: a mining town in the Ruhr, population 300,000, two theatres, one subway line, and flat sidewalks. Jan Klata: a sloppy Mohawk, military uniform, and a gleam in his eyes. The German press has taken particular notice of the Polish theatre director’s “underground” appearance. He doesn’t particularly inspire trust, and the date of the premiere did little to help — Kafka’s Amerika opened two days before Mayday, a holiday for punks and revolutionaries throughout Germany.

Franz Kafka, Amerika, dir. Jan Klata,

Franz Kafka, Amerika, dir. Jan Klata,

Schauspielhaus Bochum,

premiere 28 April 2011 And revolution in a small, conservative town is what they fear most. While the citizens of Bochum have had time to come to terms with the new, independent vision espoused by the Schauspielhaus since the change in management at the start of the season, the theatre has thus far only hosted calm, tame directors. And not only was Klata from Poland — the Wild East — he was taking a shot at Kafka. Their Kafka.

The opening scene of Amerika is a test of trust. The audience sits restlessly, the curtain is raised, and bare buttocks appear on stage. A couple in the first row stands up and leaves. Things only get more intense from there.

An enormous paper ship is hauled onto the stage. At the top stand men decked in American football gear, ostentatiously chewing gum. At the bottom is Karl Rossman in a recognizable Chaplin-style hat and an old-fashioned suit. His is the only role in the production with any ties to the aesthetic of the Kafkaesque character. The outfit emphasizes his innocence, and conveys both his background and opinions, of which he will be stripped (along with his clothes) as the play progresses. He starts off fresh and lost, standing in front of the overwhelming ship and holding a naked engineer by the hand. America is one great mystery to him.

German critics on Klata (1)

“The Polish theatre director Jan Klata has never been to the United States. His perception of American thus remains unspoiled. He notices that which is most important: cultural stereotypes, promises of salvation, and the gap between the rich and poor in a country where everything is said to be possible. Along with dramaturge Olaf Kröck, Klata translates Kafka’s novel into a play that doesn’t let up for a moment. The fantastic performance of the Bochum theatre company was well received.”

Britte Heidemann [www.derwesten.de]

He is welcomed to the New World by his uncle, the captain of a rugby team, who smacks his lips and utters lines from Barack Obama’s famous speech. “Yes, you can.” A few more uplifting slogans are pitched and “Empire State of Mind” (by Jay-Z and Alicia Keys) is played. The young audience picks up the melody; some people start humming, others rock their bodies to the rhythm, and the man next to me clears his throat loudly.

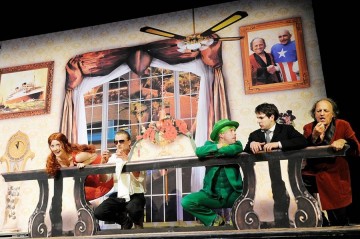

There’s no clichéd, mysterious, Kafkaesque atmosphere to be found in Klata’s production. There are no dark corridors and endless staircases. The story of Karl Rossman — a 16-year-old German whose parents send him to America after he gets a maid pregnant — is presented as a comic strip, complete with illustrated stage decorations. The pop-art formula keeps the tension high, revealing a hitherto unknown side of Kafka. The comic strip scenes flash by rapidly, with not a moment of boredom. The acting is dynamic and mechanized, like cartoons in which the chase scenes never cease, even though no one’s actually getting away. The soundtrack is a never-ending playlist of American pop hits, keeping the audience excited from start to finish.

German critics on Klata (2)

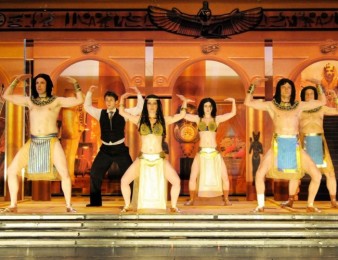

“The comic book aesthetic of the play works out well, at first. The actors exchange off-hand and highly rhythmic dialog, pacing frantically about the stage, only to suddenly slow to a halt. The grotesque costumes highlight the comic book nature of the production. Sadly, the comic element disappears in the overly-long hotel scene, in which the actors perform an Egyptian dance and simply look ridiculous. During the final scene at the Oklahoma Theatre, when we hear the beautiful statement, ‘Karl finally understood the greatness of America’, Klata creates an ephemeral image of a planet revolving amidst laughter. He nevertheless succeeds in staging an authentic, Kafkaesque theatre production.”

Regine Müller [www.nachtkritik.de]

As far as Kafka goes, the play is rather funny. The adventures of Karl Rossman are exaggerated sketches in which the characters incessantly trip, bump into each other, and experience wardrobe malfunctions. The production’s German, slapstick style is sure to keep many a conservative malcontent in their seat. The laughter of the audience drives scene after scene, which seem to explode thanks to the excellent stage design by Justyna Łagowska. Like a children’s pop-up book, the paper set decorations unfold, only to collapse with a bang a moment later.

The sly American references peppered throughout the play make things even more interesting. Everything is “super” or “mega”, and the new continent is portrayed in a mocking light. If there’s a bar, it has to be a trailer out in the desert, with a curtain of beads instead of a proper door. If there’s garden decorations, they’re plastic pink flamingos. If there’s a monument, it’s a statue of Ronald McDonald.

photo: Thomas Aurin, Schauspielhaus Bochum

photo: Thomas Aurin, Schauspielhaus Bochum

Klata projects his own clichés onto Kafka’s vision of America. The cliché of a European whose heritage is being devoured by the primitive consumer culture of the United States. Klata has never been to America. He doesn’t need to go. He’s got the U.S. on every corner, on the radio, at the movies, and at the mall. And he is very afraid of it.

German critics on Klata (3)

“It is difficult to do justice to the hermetic yet precise language of Kafka in a theatre production. Kafka might even be the antithesis of theatre, narrative, dialog, and dramaturgy. Klata has nevertheless succeeded in staging a ‘comic book play’ based on Kafka’s disturbing novel.”

Regin Müller [www.nachtkritik.de]

The Germans were right to have their reservations about a punk director: Klata sparks a true revolution on stage. The thing is, his revolution has a slight strawberry taste. It’s supposed to be fierce and gallant, but there’s still a bit of sweetness and fun to it. The director serves up his anti-capitalist world-view in a pretty box with a big bow, and the audience is more than happy to repay him with their applause. Why would you want to be lectured on imminent threats, cruelty, and the thirst for power, when you could just give yourself a solid kick in the butt and be on your merry way? Or slam shut another page in the book/set and forget about the problems of our cruel world.

Kafka’s Amerika is a study of the demise of a man, a portrayal of an exploited society, and a crack at capitalism. Klata’s Amerika is everyday life portrayed in a series of photocopies. It’s a game he consciously plays with the audience, of course, one heavily influenced by MTV and American sitcoms. What’s missing is a decisive ending that would subvert that convention, one that would enable the director to show us the truth instead of just winking at us. That could have happened in the final scene, where all the Candyland decorations drop to the floor and Karl faces the world alone, but by then it’s a bit late for suspense. Perhaps “Karl finally understood the greatness of America”, as an off-stage voice announces, but the audience had no hope of doing so.

photo: Thomas Aurin, Schauspielhaus Bochum

photo: Thomas Aurin, Schauspielhaus Bochum

translated by Arthur Barys