In the wake of last year’s Gdynia Film Festival, much was said about the verdict and about how the international panel of judges underrated Wojciech Smarzowski’s Rose. But there was a film that was treated even more unfairly at the festival in Gdynia: Andrzej Barański’s The Heritage, which didn’t even qualify for the main competition. Today, nearly a year after its premiere screening, the film is being released in Polish cinemas.

Like in many of his previous pictures, Barański turns to literature for inspiration in The Heritage. This time, it’s three novels by Zbigniew Masternak: Chmurołap (Cloud Catcher), Niech żyje wolność (Long Live Freedom), and Scyzoryk (Swiss Army Knife), in which the author tells (fabricates) his life story. He grew up in a poor village outside of Kielce, in the home of an alcoholic father and a mother who dreamt of a better life and an education for her son; a series of failed attempts to escape his parents’ world through football (a career brought to an end by an injury), law school (from which he never graduated), and finally business and criminal activities.

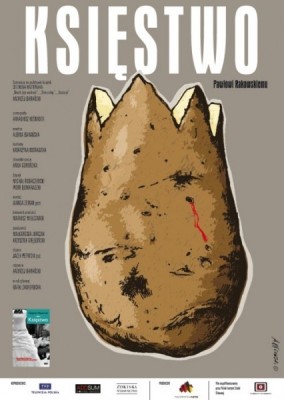

Księstwo, dir. Andrzej Barański,

Księstwo, dir. Andrzej Barański,

Polska 2011, in cinemas from May 2012Barański takes great liberties with Masternak’s prose. Not only does he compile and condense three novels into one film, he also changes the ending, giving the entire story a tragic dimension. In narrative terms, the entire picture resembles a tale spun by a village storyteller; the plot goes from one anecdote to the next, like gossip swapped over the fence by next door neighbours. The abrupt finale becomes all the more powerful thanks to this structural technique.

The main character of The Heritage (played by the excellent, unpretentious Rafał Zawieruch) returns – to use the words of a Jacek Kaczmarski song – “whence no dream came true” (the city, the world of football), “where the worst fortunes come to pass”: his family village, where there are no jobs and no prospects, and where most men slip into alcohol-fueled despair. Barański’s picture is full of the iconic imagery of the Polish countryside that we recognise from films and the media: drunks, elderly villagers in threadbare clothing, warped wooden fences, and even a women who all but literally barks at passers-by from behind her fence, like the peasants in Witold Gombrowicz’s Ferdydurke. But the director doesn’t fall into the easy stereotype; he views the world which the character struggles to escape with sympathy rather than contempt, and he doesn’t turn it into an exotic attraction, an anthropological picture for a big-city audience. Rural Poland in The Heritage is grimy, unpleasant and stuffy, but Barański lets its inhabitants keep their dignity, even though they’re often grotesque, hideous, amusing, disorganised and incapable of the serious, consistent work that separates grownups from children. The immaturity of the adults is best portrayed in one scene in which a roadblock is dispersed when a truck driver bribes the villagers with his cargo in order to pass.

Barański avoidance of stereotypes starts with the very form of his picture. The Heritage is beautifully shot in digital black and white by Jacek Petrycki. The clean, almost pure photography makes the world and story depicted in the film seem more distant, keeping the picture from slipping into either the banality of a made-for-TV film or the cheap magic of 90s Jan Jakub Kolski films. Also notable are the three intertwined linguistic registers: the rural dialect used by most of the villagers, the educated Polish adopted by the main character himself, and the pseudo-medieval “knight” speech used by members of the brotherhood of knights with which the character is associated for part of the story.

It is the main character’s alcoholic father who fills his son’s head with tales of knights, telling him stories about the powerful Vistulan dukes from whom the family is supposedly descended. The father’s legends and the mother’s desire for him to receive a proper education result in the main character growing up to believe that he is somehow better than the world around him, and that he must find some way to escape it. But his escape takes him to the very place in which it began. The Heritage is, in this sense, a story about a failed attempt at personal emancipation. Perhaps it is failed because instead of questioning the binary opposition between the “noble” and the “peasant”, the character only tries, unsuccessfully, to distance himself from the latter pole of the opposition. A seemingly “private” and “nonpolitical” artist, Barański thus touches a living political theme that our own community must face; a community that, in many ways, is struggling to escape “village life” and “peasantry”, but remains incapable of overcoming the divide between the “noble” and the “peasant”, steeped – like the main character’s father with his stories about the “Vistulan myth” – in delusions about an aristocratic past with its palaces and coats of arms.

translated by Arthur Barys