This theatrical statement takes as its starting point the Polish theatre world’s recent highly publicised protests against the imprudent arts policies of a number of cities, particularly the thoughtlessness of municipal governments in Warsaw and Lower Silesia. The protests are mentioned in the very first scene, where Amy Winehouse (Agnieszka Kwietniewska) apologises, with tears in her eyes, for the mediocre performance we are about to see; such is the result of low rehearsal attendance. The artists, she explains, were busy taking part in debates and collecting signatures on petitions. As if to preempt the audience’s reaction, she talks about how weak the performance is and how embarrassed the actors are, thus initiating a self-ironic game: a game that, fortunately, is more than just a clever “we meant to do that” sort of cover-up.

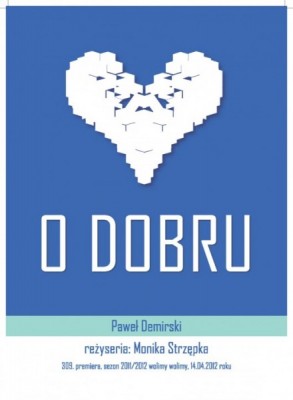

Paweł Demirski, O dobru, dir. Monika Strzępka,

Paweł Demirski, O dobru, dir. Monika Strzępka,

Dramatyczny Theatre in Wałbrzych,

premiered 27 April 2012Playing many roles and transforming from character to character, the Brechtianly detached actors appear as themselves for a change. Gosia, Roza, Kwiecia, Mirka, Andżela, Kłak and Filip: the actors represent non-anonymous and non-individual interests, in spite of the non-literal nature of the situation. What do they mean when they say it’s not just about theatre? What else is it about? They attempt to answer this question in therapy. The characters meet at a social services center in 2016, after an anti-bank revolution has swept the globe and the theatre protests have become a memory of a courageous, late-lamented past; a past as great – and just as fragile – as the model dinosaur that Michał Korchowiec puts together in the overgrown hall.

We are introduced to a group of patients that includes the legendary investigative journalist duo Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, a corporate employee, a resurrected pop singer, a social activist and a radio host struggling to cope with her show. Aggression spills out of them like free soup from plastic bowls knocked from the hands of hungry children by those who have eaten their full. In one such scene, performed outstandingly by Rozalia Mierzicka and Filip Perkowski, the authors address the issue of what, and from whom, something may be demanded. “You have to learn to be able to want to demand to ask for something”, says the therapist. In response, Mirka asks the audience to make some scrambled eggs. No one volunteers, but the person picked out of the audience doesn’t refuse. Perhaps it’s all about asking the right person? Even if the right one is the hundredth person you ask.

Dramatyczny Theatre in WałbrzychIn O dobru (On Goodness) Strzępka and Demirski clearly say that media constructs demand change and that communication strategies in the public space require strong intervention and level-headed debaters. Hence the role of the radio host struggling to cope with her show. The reference to Strzępka and Demirski’s infamous interview with TOK.FM’s Grzegorz Chlasta, which devolved into an argument and ended with the pair storming out of the studio, is important for a number of reasons. One is that the interviewees’ opinions drew just as much attention as did their choice of (swear-) words, as made evident in comments posted on numerous websites. In a way, the debate over the protests turned into a debate on language, one in which it was argued that a Polityka Passport-winning theatre director – like the Girl with a Pearl Earring – should not be heard swearing. There are certain rules in the world of culture, and those rules are negotiated by artists, who sabotage the media with their euphemism-averse speech.

Dramatyczny Theatre in WałbrzychIn O dobru (On Goodness) Strzępka and Demirski clearly say that media constructs demand change and that communication strategies in the public space require strong intervention and level-headed debaters. Hence the role of the radio host struggling to cope with her show. The reference to Strzępka and Demirski’s infamous interview with TOK.FM’s Grzegorz Chlasta, which devolved into an argument and ended with the pair storming out of the studio, is important for a number of reasons. One is that the interviewees’ opinions drew just as much attention as did their choice of (swear-) words, as made evident in comments posted on numerous websites. In a way, the debate over the protests turned into a debate on language, one in which it was argued that a Polityka Passport-winning theatre director – like the Girl with a Pearl Earring – should not be heard swearing. There are certain rules in the world of culture, and those rules are negotiated by artists, who sabotage the media with their euphemism-averse speech.

Too easily do we buy into and support media formats. When we bought tickets to Amy Winehouse’s Belgrade concert, we lent our support to her manager’s claims that drugs strengthen the singer’s vocal chords and bring out the performing spirit in her. The portrayed conflict between the vocalist and Sony Entertainment (Mirosława Żak) illustrates the rift between people’s needs and capabilities and the demands of the market, while condemning – rather subversively – the grooming the artist undergoes for the capitalist stage. Despite its humorous undertones, Agnieszka Kwietniewska’s portrayal of Winehouse’s drug-fueled career is strikingly realistic. It revisits the tension we remember from YouTube, the perverse hunt for differences and similarities. All of this is cut off with a simple question: “Why do you care so much about her when you wouldn’t give a second thought to a train station junkie?” Could it be that we just can’t stand to witness the downfall of such talented young women? Or perhaps we’ve just grown accustomed to the scratched tattoos and the sight of her teetering on high heels? Kwietniewska cuts short her rendition of “Rehab” and asks how she’s doing. We react to a familiar image: “You’re doing fine.”

As the performance draws to an end, the actors invite the audience to file out of the theatre and sing the FC Liverpool fan hymn around a campfire. From trenches to summer camps and scout trips, fires have always been a source of warmth. The image is thus a conventionally moving one, a happy ending: that’s what goodness is supposed to look like. And even the skeptics who don’t believe in happy endings let themselves be ushered outside.

The question remains whether our longing for an uplifting conclusion is synonymous with an authentic belief in its power. We’re moved, the authors say, but let’s draw some conclusions from all those emotions that our country is built upon.

I have doubts as I read the protest letter I signed. Not about whether it was the right thing to do, but about its portrayal of the relationship between the theatre and the market, according to which the theatre, in its aspiration to rise above the rules of the market, could in a sense be removed from it. The statement is vague in that spectators prefer to see themselves as participants in a discussion rather than customers, an yet they still have to buy their own tickets. The point is that we should be free to buy tickets for whatever we choose, and that theatrical offers should be composed competently for audiences that happen to be customers, not the other way around. This is why I view O dobru as a commentary on how moving it was to see the theatre world come together around a common and honest goal and react swiftly and decisively. The theatrical fan zone is a zone of common interest.

Therefore:

translated by Arthur Barys