Berlioz wrote The Trojans as a two-night performance: the first takes place in Troy, the second in Carthage. Some present at the Warsaw performance stood up and left before it became completely apparent that the actors’ rhetoric and the entire videosphere of the show were an element of play, and not a perpetuation of clichés and cheap tricks.

If you have a language, you have it all. The styles were the same, but the languages are separate. Fura refers to a theatrical style created by the theater group La Fura dels Baus. The style has an uncommon capacity for communication, a quality put to use by the producers of Berlioz’s Trojans: Padrissa, Olbert, and Riera. It encompasses entire artistic territories, and is highly musical. It has kept pace with opera on many occasions: in Debussy’s Martyrdom of St. Sebasian, de Falla’s Atlantis, Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust, and Mozart’s Magic Flute.

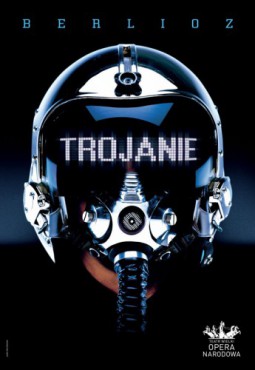

The resonance between Fura and Berlioz is odd in that the narrative strategies of the two seem to have conflicting intentions. Fura holds fast to that which is ordinary and popular, rather than that which is imaginary, and has recently embarked on a broad foray into the world of electronic media. While you wouldn’t guess by the Star Wars style announcements for the phenomenon of The Trojans, the system of Fura also sabotages the American religion of technology. In Fura, industrial materials and new technologies are used to create poetry. The self-irony in their digital shows shifts us towards the more human end of the scale. Their sources can be found in counter-culture, but also folk culture and the culture of Catalonia.

The heroic language of Berlioz’s libretto, compared to the eternally young, folk spectacle created by Carlu Padrissa, is emotionally and dramatically aged. Padrissa subverts Berlioz’s imperatives and listens to music. The on-screen shouts of “system failure” and “virus alert” may just as well refer to Troy itself as it may to the entire theatrical axiology, so to speak, of classicism and romanticism. It seems that we end up close to Berlioz; it seems he has been stripped of the clichés.

The compositional universe of The Trojans, the textbooks tell us, is integral, and yet there are numerous moments where this integrity bursts at the seams. There are ballet parts, a variety of entrées, pantomimes, and marches. Valery Gergiev avoided merging them with the performance, and in fact separated them physically. When the women of Troy decide to go to their deaths, the words are dramatic, but Gergiev’s version is less solemn, almost uplifting…

photo: Krzysztof BielińskiThe massive sounds of the orchestra are more imposing than usual. The director is also more subversive with the exaltation in Berlioz’s libretto: he exposes the cracks between the gravity of the text and literariness of the narrative on the one hand, and the piece’s magical soul on the other. Stage directions along the lines of “with great exaltation” invite the director to impose puppet-like gestures on Cassandra and Dido. The end result is a completely different story.

photo: Krzysztof BielińskiThe massive sounds of the orchestra are more imposing than usual. The director is also more subversive with the exaltation in Berlioz’s libretto: he exposes the cracks between the gravity of the text and literariness of the narrative on the one hand, and the piece’s magical soul on the other. Stage directions along the lines of “with great exaltation” invite the director to impose puppet-like gestures on Cassandra and Dido. The end result is a completely different story.

*

The explosion of industrial technicism occurred as Flaubert and Berlioz were writing Madame Bovary and The Trojans. It was time to leave the salons, and Berlioz dreamed of performances for audiences in the thousands, operas seen by everyone. He piled on the roles and expanded his orchestra, searching for a new sound. In that sense, he was bidding adieu to the musical asylum offered by the French bourgeoisie. Fura enjoys crowds as well, which is perhaps why Poles are less than enthusiastic about the theater company. An audience of 35 thousand is said to have seen their production of the Divine Comedy in Florence, while 500 million witnessed their opening ceremony at the Olympics in Barcelona. Fura arrives at ports in their own ship and puts on inventive shows strongly influenced by the exceptionally pure, Catalan instinct for form. And as Berlioz once did for the Emperor, so Fura put on macroshows for such corporations as Pepsi, Mercedes, and Absolut Vodka…

The story of La Fura dels Baus and Carlu Padrissa starts in the 1970s, in the seaside town of Sitges, near Barcelona. I once witnessed the work of a railway bard, no older than 12, who boarded a crowded suburban train from Sitges. He sang in a ballad-like parlando, spinning a tale ― from what I gathered ― about some ancient history. The style was unmistakable. It was the same style that Trujamán, the boy-narrator in de Falla’s El retablo de maese Pedro, uses to describe the exploits of Don Quixote. I discovered that Trujamán was based completely on folk tradition.

In The Trojans, the shiny vestiges of codified high culture also as something old, something real and ordinary. The communicativeness of the languages lets anything fly: the blue screens, the Orthodox Christian ceremonies, classic theater gestures, the Iberian retablo, plastic tubing, the devotional statuettes one finds at pilgrimages, and all sorts of junk to be sold on eBay. The performance is designed to be grand in scale, but an affinity for the unexpected remains at the peak of the hierarchy. Despite appearances, the opera works not through its reach and breadth, but through its experiments in scale. Padrissa and Olbert employ in parallel a big-screen show and a small, personal scale. The Virgilian song of Hylas, so familiar in historical reality, so well known through poetry, takes the form of an astronaut’s lone voyage. The great blue crescent of the Earth glows in the background. Poor Hylas drifts off into space, bound to his spacecraft by a thick, oversized cable, longing for the Earth to which he will never return.

*

Berlioz wrote the monumental Trojans as a two-night performance: the first takes place in Troy, the second in Carthage. Some present at the Warsaw performance stood up and left before it became completely apparent that the actors’ rhetoric and the entire videosphere of the show were an element of play, and not a perpetuation of clichés and cheap tricks. Cassandra, with cleavage exposed, and the noble Coroebus danced together according to the classic formula, which calls for the actress to intensify her voice by supporting herself on her partner. Cassandra later tears Coroebus’ laptop away from him in a fit of rage, smashing it on the floor, and the computer disintegrates with an embarrassing, plastic thud. This episode is merely a preview of what is to come, a insertion of electronics into Berlioz’s opera.

It later becomes apparent that all the great digital props and the Trojan Horse itself are a mere demonstration of the toys of a childish society. But Padrissa doesn’t criticize this society ― conversely, he celebrates it. Enormous networked appliances meet again and again on stage with the everyday objects of an agricultural society ― clumsy, yet treated with tenderness.

When Aeneas and the others call for war with the Libyans ― the Polish translation uses the memorable line from Stanisław Wyspiański’s November Night: “To arms! To arms!” ― and everyone briskly prepares to massacre the Africans (“Towards the terrible African hordes / We march / march together”), enormous industrial pipes set up on stage leak air (are they playground tubes?). It is a disgrace to Berlioz’s correctness, and at once a parody of the on-screen orgy of writhing dragons that the audience is forced to endure because of Laocoön in the Trojan half of the performance. The wars ― Trojan or Libyan ― are hard to tell apart from the endless carnival, and the parody is completed by the folk/royal fashion show, a perverse online event featuring machinery built into the bodies of the models and canine sex models on leashes. Despite the tricks, we listen carefully.

Laptops appear in the hands of the choir. The ceremonial choir, dressed in long robes with a splash of purple, closes them in a circle of magical procedures, or sways over them as if in ritual. The laptops are no longer computer equipment: they have become tools of wizardry. The flickering line of magical screens reflects the sky.

*

Dido’s sister, clothed in a winged dress in the style of the Third Empire, takes mincing steps. It is pure opera, the 19th century technicism of stage puppets, and at once a folk parody of the upper classes. The passion of beautiful-voiced Dido is expressed through irate hand gestures, as if they were tied to a string. Next we see the apotheosis of lovers, lifted into the girders in meshed containers resembling capsules as much as chapels. After their departure, enormous rings appear once again, covered in innumerable screws, but they are duds made of flimsy plastic. This doesn’t keep us from being moved. A multifunctional conch shell (Dido’s sofa), a prime specimen of provincial upholstery art, flips over, covering the poor girl like a bell jar. If it is a tomb, then have we arrived at the destination of our pilgrimage? The people went off in some direction, they sang, there was a war, it didn’t really matter who was on what side; war, scourge. People died, played, prayed, and cheered.

In the end, the laptops are delicately arranged, gingerly adjusted to make sure they shine just right. The tiny monitors reflect the sky and the skeleton of some building. The images flicker, the eye of a deity winks. The language of the internet becomes symbolic speech. A network variety of sacral figuration. But then an unexpected object descends, something like the cover of a manhole or a pickle jar. Dido steps onto the cover and, for a moment, looks like a Catalan Virgin Mary. A subtle mockery of technicality, stifling the sentimentality that just might slip in while we listen to the sobbing of Dido.

translated by Arthur Barys