GORAN INJAC: The exhibition “Gender Check” made use of the concept of Eastern Europe. Isn’t it patronising to suggest that an entire region should appreciate this opportunity to present itself as “the positive other”?

TANJA OSTOJIĆ: I believe that when it comes to artists from Eastern Europe and the Balkans, the context from which they come and in which they live is one of the most important ways of understanding their art. Of course, it’s also important to see where the artist steps out of that local context and touches upon more general issues about the times we live in.

Tanja Ostojić

Tanja Ostojić was born in Serbia in 1972. She is an interdisciplinary artist and performer, and a graduate of the Art Academies in Belgrade and Nantes. In her work, Ostojić explores ― from the feminist perspective ― social and political power relations, and the issues of immigration, exclusion, and responsibility. She often plays the main role in her interactive artistic events. Her work has been displayed at many individual and group exhibitions (including Re.act.feminism in Berlin, the Venice Biennale, Performa in New York, and Manifesta 2 in Luxembourg). Her art is the subject of the book Integration Impossible? The Politics of Migration in the Artwork of Tanja Ostojić (argobooks, Berlin 2009).

The exhibition “Gender Check” at Warsaw’s Zachęta Gallery last year (March 20 – June 13, 2010) featured two of her pieces: the project “Looking for a Husband with an EU Passport” and photographic documentation of her “Personal Space” performance.

But I think there are certain qualities that are characteristic of authentic works of art from the former Eastern bloc. In most cases, there is a certain solemnity, tragedy, and depth about their work, like with Dostoevsky ― a feeling that the artists grew up in a different aesthetic as well as in a different system of values, in a space of great crisis, and at the same time, with a characteristic sense of responsibility for something that I would call a mission to shape meaning. Another significant factor is the different context of artistic production ― theirs might not necessarily be the kind that is subject to the demands of the art market.

In your case, the place where you grew up and the issues you address in you work are inextricably linked. You’re interested in such topics as a “better” and “worse” Europe. One of your projects involved an illegal crossing of a national border.

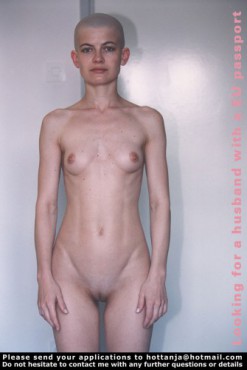

Tanja Ostojic, Looking for a husband

Tanja Ostojic, Looking for a husband

with an EU passport [2000-2005]

courtesy of the artistAn even better example is my interactive project, the website “Looking for a Husband with an EU Passport”. Even though the project is over, and I’m divorced and without the “better” passport, I still use the physical, political, and economic borders of the European Union as a subject for research and provocation.

That was a very particular form of provocation. “Looking for a Husband” involved the radical politicization of the personal and intimate.

As a true feminist, that is precisely what I do: I make the personal political. I used my own passport in this project as evidence of my social and political existence, as well as my own body, with all its gender, racial, and temporal characteristics. That was the idea: to use my own body and my own history to problematize all the restrictions involved with visas, legal residence, and work permits, freedom of movement, and the right to citizenship in the land of “Schengenia”.

How exactly does one turn a piece of their own biography into a work of art?

The project took five years. I started it in August 2000 by posting a classified ad. Hundreds of letters poured in, I chose a candidate, and then I met my future husband on a date that took the form of a public performance. We then got married, I moved to Düsseldorf, and finally, we got divorced (“Divorce Party” opened my exhibition titled “Temporary Integration Project Office” at the Project Room Gallery 35 in Berlin). This involved repeat appointments at the embassy, innumerable visa applications, meetings with the immigration police, and all the hoops that you have to jump through when you want to marry your way into a better, EU world. I didn’t succeed, and didn’t even get permanent residence card. That about sums it up. In order to secure rights which ― according to European Union law ― I have no right to have, I consciously and quite literally employed strategies that were outside the boundaries of the law. Just like in my 2000 project titled “Illegal Border Crossing”, the point of the tactic was to expose the illusiveness and selectiveness of the noble rules of democracy.

The female perspective gives that piece its strength. If some artist were to attempt a male version of the project, let’s say “Looking for a Wife…”, would the result be equally powerful?

Integration Impossible? The Politics of

Integration Impossible? The Politics of

Migration in the Artwork of

Tanja Ostojić, argobooks, Berlin 2009

courtesy of the artistThat’s not a question worth answering hypothetically; it would be more interesting to actually try it [laughs]. The archives of my “Integration Project” and my handmade “Wedding Book”* both contain statements by people who have also chosen marriage in order to get EU papers. One of them is an artist from Priština who got married in Berlin, and a gay man from Belgrade employed in the cultural sector, who got married in Brussels. The difference is that they did not turn their decision and marriages into art. The documentation of the project also contains three examples of interventions on my own body ― on the photograph of my body attached to the “Looking for a Husband” ad ― conducted by members of LGBT organizations in Belgrade. These modifications make the classified read more like an ad by a man or transsexual looking for a husband with an EU passport. This makes the whole story even more complicated, especially if you keep in mind that being gay is still a taboo subject in Serbia, and members of the gay community face terrible social pressure and are often the targets of aggression.

Were you trying to make this project a type of personal intervention?

The main thing I wanted to do was to talk about the exclusivity of “Schengenia”. And to show one possible strategy for crossing the border, a strategy that emigrants all over the world have been forced to use for over one hundred years. The media and the EU’s discriminatory laws, which constitute some new form of colonialism, often treat emigrants as an abstract, alienated, homogeneous group. An important aspect of my work involves juxtaposing personal and direct statements with this abstract perspective. Besides showing myself and my private story, I collected the personal stories of other people, all to provide the viewers with a variety of individual points of view and to help them appreciate the gravity of the situation. I wanted to let the viewer identify with me, with them, and with us.

Pictures of your “Personal Space” performance were also on display at “Gender Check”. That performance placed very particular demands on the audience.

I performed “Personal Space” for the first time at the 2nd Yugoslav Youth Biennale in 1996. My head, face, and naked body were shaved and sprinkled with white marble dust. I stood motionless for two hours in a square sprinkled with the same marble dust at the official opening of the exhibition. The dynamic of that performance was primarily an internal one. Careful viewers could follow the changes in my internal state ― just like in a silent movie ― by observing my eyes, face, my position, and my breath. My fists, for example, would tighten when I felt tense, and would open back up when I felt relaxed. It all depended on who was looking at me, and how they were looking at me. The piece communicated with viewers ― who automatically became participants of the performance ― through an unbelievably powerful and profound exchange of energy. But “Personal Space” was also about showing the lack of space for individuality and about testing the boundaries of individual identity in relation to local and global frustrations.

I think that performance was, to a great extent, a response to the reality of life in Serbia in the 90s. Did you ever repeat it in other circumstances?

I performed “Personal Space” a few more times in different parts of Europe, and I never felt that I was merely repeating it. The circumstances completely changed the expression of the performance. But when Bojana Pejić invited me to do “Personal Space” at the closing of “Gender Check” in Vienna, I refused. Fourteen years have passed since I first performed it ― times have changed, and so have the problems.

How does your art work in the public space?

I think it works quite well. Exhibitions at cultural institutions are usually not the end of it. I appreciate things in art that are precise, have deep political and social justification, and are conducted for a certain purpose. I appreciate a sense of humor and consistency, but I also appreciate a readiness to take risks and responsibilities, as well as a sense of empathy. For that kind of art, the public space is a natural venue.

*Of the two existing copies, one was displayed at the Zachęta Gallery, as part of the “Looking for a Husband” exhibition.

translated by Arthur Barys