The Negro as slave is one thing.

The Negro as American is quite another.

— Amiri Baraka

KATARZYNA BOJARSKA: Would you consider yourself an American artist? One who operates in a specific territory: geographic as much as mental, and also within a specific art context?

KARA WALKER: I think I am. I feel it more and more. Especially when I am changing places. To be black in America, even calling oneself African American is a political act, because for so long blacks have not been considered full citizens, barely even full humans in the eyes of the United States.

So it is a kind  Kara Walkerof an interesting and a meaningful gesture to say: I am an American female artist and I belong there. You know there was even a time when I would say: well I am black, so not really American. There is an Americanness as a sensibility in my work and also the influence of a lot of things I was and am looking at. There was of course the European influence too, but I was interested in American art and how American artists try to represent themselves and – what I find especially intriguing about America – this idea of emergence: people finding some sort of impetus to define themselves against the Past. That strikes me as a very American approach.

Kara Walkerof an interesting and a meaningful gesture to say: I am an American female artist and I belong there. You know there was even a time when I would say: well I am black, so not really American. There is an Americanness as a sensibility in my work and also the influence of a lot of things I was and am looking at. There was of course the European influence too, but I was interested in American art and how American artists try to represent themselves and – what I find especially intriguing about America – this idea of emergence: people finding some sort of impetus to define themselves against the Past. That strikes me as a very American approach.

I recently came across Touré’s book entitled Who's Afraid of Post-Blackness where he looks for new approaches to confronting today's structural inequalities in black America, i.e. “free, but not equal”. The title of your lecture in Warsaw refers to an age of race fatigue. Could you speak a little about this fatigue? Do you consider yourself an artist of post-blackness, one who would take for granted what the previous generations fought for?

I’m not sure. Every time I hear the term post-blackness it seems inadequate. I understand the intention behind it, but it seems too quick, somehow. It’s too easy a term to me, a label actually. It seems to encompass something that is not really necessarily a solid thing. It is mostly referring to art and there is kind of a break with a more referential take on black history, identity politics, social responsibility, art. So whether it is post to reject that or to look at it with a jealous eye, I’m not convinced.

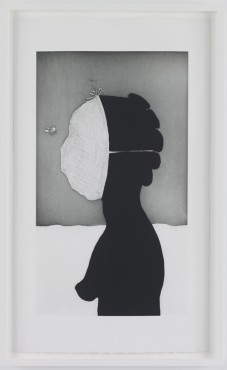

Kara Walker, An Unpeopled Land

Kara Walker, An Unpeopled Land

in Uncharted WatersIt seems similar in a way to the idea of the post-colonial. Many critics and historian claim we can’t actually speak of the postcolonial since we still live in the era of the colonial.

Right, and the mindset is still very much colonial no matter how post it is. I guess this is what has been bothering me about Touré’s book. However, I do think my point of view reflects a real frustration or even schism between the hard fought ideology of Freedom and the slovenly capitalistic result. Consumerism has replaced the mythical American “can do” spirit. It neutralises and equalises middle class yearnings. Eliminating the need for racist constructs, except for nostalgic purposes. “Post Black”, or rather Touré’s book, represents that nostalgia for a definitive (even if multifaceted) black culture.

Let us dwell for a moment on the issues surrounding the notion of identity and self-definition. Since I’m a great fan and admirer of the character of Kara Elisabeth Walker as an Emancipated Negress and a Leader in her Cause, I would like to ask you who she is and whether she is still alive?

I am not so sure if she’s still alive or not. And there have been many (long) names for this character. Part of that was trying to create a complete space and implicate the artist and the institution as complicit in this ongoing game of misidentifying identity. I guess for my most recent gallery show, I came back and started to refer to myself from the outside as something more closely resembling myself, but as a satire: “Dr. Kara E. Walker”. But the Negress is the idea of the rebel. I was drawn to this character probably already in graduate school. I remember when I was reading Thomas Dixon Jr.’s The Clansman¹ – even when I purchased that book, I felt it was an extremely subversive act. I was living in the South, I was working in a bookstore and somebody had ordered it from this small unknown publishing house which was still publishing this kind of literature. It was fascinating reading. In the course of that book there is this character described as a “Tawney Negress” who is presented as this potentially powerful, dark-shadowy, sexual figure sidling up to power. And when I was thinking about the trajectory of my work at the time and as I divorced myself from painting and started thinking that I am actually in the space where everything is sidling up to power within these spaces of opportunity and importance, I decided to take on this identity.

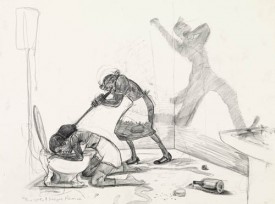

Kara Walker, The Great Negro HeroineHer (your) long titles as well as the long titles of her (your) works and exhibitions, with all their wit and playfulness, made me think of the still not-unproblematic relation between the humour, the grotesque, the horror, and the violence of actual historical events. I am wondering how you managed to negotiate your path through all these boundaries surrounding the representation of sexuality, race, and trauma.

Kara Walker, The Great Negro HeroineHer (your) long titles as well as the long titles of her (your) works and exhibitions, with all their wit and playfulness, made me think of the still not-unproblematic relation between the humour, the grotesque, the horror, and the violence of actual historical events. I am wondering how you managed to negotiate your path through all these boundaries surrounding the representation of sexuality, race, and trauma.

It is a strange thing in a way, because when I think back to when I first showed my work in New York, I think what I was doing at that time was so antithetical to everything else that was happening in contemporary art: you know I was drawing (and nobody was really drawing at that time), I was doing cuts, speaking through this anachronistic language. All that was playful for sure but, at the same time, it was totally over the top; much too much: too many words, too many pictures, too many types of intervention into the visual, to what was common, expected and necessary and what was important. I didn’t care about all these things. Now, after all these years, the impact has been reduced. I have just recently found some reviews of some of the early shows and it I realised it was a shock. Even the language the critics were using to describe what was being shown was so shocked, as if they lacked words to even describe what I was depicting, because they were accustomed to one kind of articulation of black subjectivity that was not the one I had chosen.

Part of what I called playfulness is, to me, a kind of celebration of who you are rather than trying to explain who you are and make others understand you and accept you as you are.

I always really liked that P.T. Barnum-style chutzpah of announcing a show in New York. Especially at that time, I realised one could say anything and people believed this fiction up to a point, so why not just say: I am an amazing Negress of Noteworthy Talent! In many ways, by not taking the Art World very seriously, I inadvertently became a serious artist.

Kara Walker

Born in California in 1969, Kara Walker is an African American artist best known for her room-size tableaux of black cut-paper silhouettes that examine issues of race and gender. Her work transcends the boundaries of media, conventions of representation, and political correctness, dealing with such topics as the traumatic history of African Americans in a way that is often grotesque and terrifying. At the age of 27, Walker became the youngest recipient of the prestigious MacArthur Foundation genius grant, launching a controversy in the African American art community. She currently lives and works in New York, where she teaches at Columbia University.

Walker’s exhibition at CSW Zamek Ujazdowski runs until January 15 and is the artist’s first show in Poland.

What I find most disturbing and crucial about your decision is that very gesture to ask once again whether there exists such a thing as the one and only appropriate form for addressing issues of importance such as historical or personal traumas. Speaking of form, as you have already said, you work in all sorts of media: I’m wondering whether your move towards these “grand narrative” structures of the cut-out murals, panoramas and cycloramas – and by narrative I mean something that expands in time, as a kind of (her)story and is related to language – could be treated as a next step you took in your thinking and working with the word-image relationship? Would film then be a final step?

Well, I am still trying to understand film. It’s tricky because I find myself moving backward and forward between images and words (physical words, written and not spoken) and I’m still in this place where I keep finding their separateness. I would bring them together and realise that there still is this kind of separateness that I enjoy. Like this kind of stationary thing: when you are looking at still images and you are forced to move something internally that you cannot name. And it’s not as passive as watching video or movies where things are being revealed over time. So I think that even if I am making those videos I am undermining them in a sense; there is a part of me that wants to come back to this place, like in the video Miss Pipi there is this three-minute section that is just this fight between two men, and there is this one blues song that plays. And really, this is all I wanted to do. It is kind of narrative and there is a song that is coming from this subjective position of a victim but then... and there is no conclusion. So I feel, as I propel deeper into the narrative format, I start resisting it and trying to find something else whether it is just a visual format or something textual. I can't keep from deconstructing before it is even fully constructed.

Your work seems to be organised by the tension that is constantly re-staged or re-enacted between you and the viewer/reader. I would even say that you do not so much deconstruct the existing representations as much as the potential representations that every one of us brings with her or him to the gallery space. At times it can be even embarrassing once you realise: oh, that's what I have (had) in mind.

Yes. There is also a kind of thing for me why I have this semi-alternate personality. I think there was this kind of cathartic moment at some point in my life when I realised all that was in my imagination: all these unthought thoughts, images, etc. First it was just collecting them, everything and anything: images from different sources, some derogatory, some not. Going back to them is like looking for some point of origin.

Part of this “collection” of yours was published as a visual essay in the catalogue published in 2007 by the Walker Arts Centre. This reminded me of the avant-gardist practice of collecting and putting images together, which has been performed by so many great artists and thinkers from Hannah Höch, Bertolt Brecht to Zoë Leonard, Gerhard Richter and others. And I began wondering, how did this weird museum of your begin? What is the origin of your way of thinking with images?

Actually, it has been in storage for so long. I have just recently started unpacking it. There were couple of events. The first was probably in the late 1980s. There was a Marlon Riggs² film Ethnic Notions (1987) which, among other things, was about all these collections of black collectibles such as little objects and images and all these caricatures mainly from the 19th century and through to the 20th century. It was kind of controversial. Even though there were many black collectors collecting these things, many people of colour just did not want to see them. It seemed to be a weird equivalent of death to have all these images around you. There were a lot of cultural battles whether these images and objects should be kept or destroyed, circulated or not. And at some point in the early 1990s someone gave me this photographic postcard and from then I started going to these antique markets. There was something thrilling also about going to these spaces where even though I feel pretty OK about myself, when I find myself in the places where a black girl is not expected to appear, it feels uncanny. Especially if you browse in the section: “Black”. So I would buy a few things here and there. My research was cyclical: anything that was representative of a black or a woman, then from there that could be historical or contemporary; then women: historical and contemporary; coming into being was another category which included the emergence of African-American identity and the emergence of white American, or just say American identity and within that the constructions of blackness. So anything I could find comported in those or maybe added some unexpected branch between them.

So the visual essay for the catalogue was the only attempt to actually show this archive of mine: by putting them together and displaying them. Other than that I have never organised it in a way for it to be seen or displayed. It just sits there in my studio and waits for the moments of activation. At some point I put it aside, being tired with all this imagery. I believe I experienced a political awakening: I cannot live with this all the time, they do not go anywhere.

Don’t they?

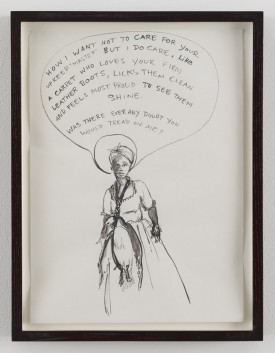

Kara Walker, Untitled, Courtesy of

Kara Walker, Untitled, Courtesy of

Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York(Laughing) Yes. They just keep sitting there with their butts bare with their lips too big. I guess it is time to take it back again and look. Stereotypes seem to persist. When the current president was running for office, all this racist shit just came right out from wherever it was sitting dormant and it was circulated in new, post-modern ways. So I went online to dig for what I started collecting 20 years ago as postcards.

The question very closely related to what we are talking about here is that of shame. Some critics would call your work “shameless”, meaning it in a non-pejorative way.

No, shameless is just full of shame. It does not mean I do not care. There is something funny about doing art. Even more so in the context of the art I am doing: dealing with all these issues sentenced to collective repression: histories and images. It is a weirdly shameful practice. At least exposing things: relinquishing the shame and spreading it around for everyone to feel and/or enjoy, depending. I guess there is something manipulative about that.

There is more to it, I believe, especially in the context of history that involves a female component. I am thinking here of the shame imposed on the oppressed. We all recall statements along the lines of “let's not talk about it and respect the dignity of that woman.”

Yes. Let’s not talk. There is this book that Howardena Pindell self-published a couple of years ago entitled Kara Walker No/ Kara Walker Yes/ Kara Walker? which is literally a Kara Walker hate book. What she did was to ask a bunch of artists and writers to write small essays on my work. It is hard to read because it is very “anti”. But it is also very interesting in the way it talks about shame. Not only that I bring up shameful ideas, shameful opinions, that I am eliciting shameful feelings, but that I am unravelling them. This the strange idea I have about freedom: be free to say and show whatever there is in your shameful heart or shameful imagination. And I am tired of this idea that European male artists are presumably inclined and required to say whatever they want — why shouldn’t I? It’s as critical and as important. So why should I restrict myself to absolutely proper or respectful things? Art is not necessarily the place for respect.

Besides, the notion of respect is a historical and cultural construct prone to change and interpretation. Yet “the proper and the respectful” are constantly enlivened and reactivated whenever the (not-so) solid social or cultural entity is shaken in its basis.

On the other hand there is this thing that happens in the States a lot which is like a constant and total revelation of the self which is supposed to be this cathartic thing, which is also shamelessness, but there are rules in it. And let’s think of 19th century slave narratives, which are full of rape, unequal relationships, and violence. This narratives however often end up in the form of kind of redemptive narrative.

There is, however, a possibility that a totally uncritical and unselfconscious viewer comes to the show and enjoys it, identifies with the stories you are telling, but with the wrong guys, and feels at home.

This happens all the time, all this weird misreading. And there is no optimal place for the work; well you can laugh a little, but not too much. It is a complicated situation. You know, I did show my work once, early on in Atlanta, where I grew up. And it was something I never did again, unfortunately. I had a major piece, The Battle of Atlanta, that was like a side show to a major show (at the Nexus Contemporary Art Center, now called “the Contemporary”). And there comes this old lady who claims that it reminds her of her childhood, and her grown son was standing next to her struggling to nuance her reaction and downplay the potential of its real meaning. Basically trying to tell me, the artist, that there was nothing to say. And this puts me in a difficult position: I don’t want the old lady to feel like I slapped her around, but I do want her not to feel fully comfortable. There is the charge of this complicated interpersonal dynamic between black and white, between different generations, and all these voices saying, “you can't say this” “you can't say that”, but I just did and there’s nothing I can do about it. The power of it has not shifted from one to the other, and it hasn’t dissipated this kind of charge. I like that. But one of the criticisms I’ve gotten, and am still getting actually, is that the black viewers of my work feel really uncomfortable in the face of my work, especially in a mixed setting.

Is it because they feel looked at in that distorted way?

They feel looked at and objectified. It is one thing to see the work on your own, and another to see it and be seen (seeing it). I have heard folks say, “I felt like laughing but I looked around and there was someone looking at me...”, which is, again, all about shame and people holding on to their shame. I like it however, that there is an occasional gallery show where there is a mixed audience. Because that doesn’t happened very often.

I do think that it is all in the eye – or imagination – of the beholder. Those responses tell us very little about your art and a lot about people who look at it or refuse to look at it (and expose themselves). As long as people have their own eyes/I’s the risk is there. It is a good meta-comment, though on the contemporary art world. I hope Polish audiences will not treat your show with an enforced dose of distance which will allow them to read it as a story of a faraway and long ago, but rather that they will indulge in an effort to disarm the metaphor and allow themselves to give up the comfort of distancing.

To conclude, let me ask you about your most recent works. What are you working on now?

I was working on a big group of large-scale drawings for the last show that I had in New York, at Sikkema Jenkins Gallery, entitled Dust Jackets for the Niggerati—and Supporting Dissertations, Drawings submitted ruefully by Dr. Kara E. Walker, and also on the text pieces with block-letters. I think I need to go back to the text, because I wasn’t really happy with the way they were going. They were sort of quotations drawn from other sources. That was OK. But I was trying to find a way to own my own writing and make it visual. Part of the language of those pieces was about the early 20th century black migration to Jazz identity, construction of the self and the destruction of rural black identity. Along the lines of Harlem Renaissance – bodies moving to the urban centres and how this destruction of fixed identity is also a self-destruction. I had a group of entries, like Wikipedia entries, about some jazz musicians who died, all these archetypal women like Billie Holiday or Dinah Washington, but also there is this specific language there about the tragedy of being a famous woman performer. I did five of those and decided to put them aside for now. I have a couple of projects that I am working on. They go in the direction of installation and drawing, but I do not know yet if there is going to be a video element in that too. I keep on thinking about doing a kind of performance and I keep not doing it.

Your development seem much more circular than linear, you keep going back and forth.

Exactly. I get tired with things and I don’t want to be identified with one of them, I don’t want to be the cut-out artist, and I’m constantly moving in various directions to check all these different possibilities to exercise my artistic freedom and the variety of histories. I am still concentrated on how representation changes — my “little black studies”. It moves away from a very specific, unifying stereotype of servitude and into this very ambivalent space which is kind of progressive but never fully present on the global scene.

It seems to me the problem also emerges every time one realises that the cause for which one could be a leader never is one. There is a multiplicity of competing causes.

Couple that with a multiplicity of competing identities and one has the makings for a colossal breakdown of normative structures. Maybe that is why jazz is always spoken about with such fervour; it began as an art that was in clear competition with the rules and timing of western music. And now it is the canon from which all other popular forms of music emanate or react against.

¹ The Clansman (1905) is a part of Dixon’s Trilogy of Reconstruction; the two other being The Leopard’s Spots (1902) and The Traitor (1907). All turned out to be best-sellers. Presenting highly imaginative fiction as historical fact, Dixon used historical romance to present Negroes as inferior to whites and to glorify the antebellum American South. While he opposed slavery, he believed in racial segregation. The Clansman became the inspiration for D. W. Griffith’s film, The Birth of a Nation (1915).

² Riggs was a gay African-American filmmaker, artist and gay rights activist. He produced, wrote, and directed several television documentaries, including Tongues Untied and Black Is… Black Ain’t. He concentrated on examining past and present representations of race and sexuality in the US.