Who sets the fashions? / Who produces guns? / Who makes everyone alike? / Who dilutes your brains? / Who invents your gods? Who tells you to believe? / Who orders you to die? / Who orders you to live?*

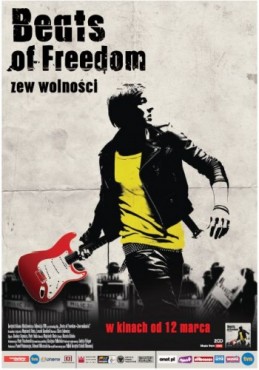

Beats of Freedom

(Polish title: Zew wolności)

A documentary presenting the history of Polish rock music as seen through the eyes of a British music journalist, Chris Salewicz. Written and directed by Leszek Gnoiński and Wojciech Słota; cinematography: Dariusz Szymura, Piotr Trela; edited by Wojciech Słota; sound: Marcin Dziuba, Piotr Fede; documentation: Piotr Stachurski; production manager: Grażyna Polańska; executive producer: Judyta Fibiger; producers: Paweł Potoroczyn, Edward Miszczak; produced by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute & TVN. Supported by the Polish Film Institute. Distributed by ITI Cinema Sp. z o.o. Poland 2010, 78’

For the premiere at the Palace of Culture’s Sala Kongresowa, the audience turnout was as impressive in terms of quantity as it was in quality. Here, though, it was choose your pick – the scale was extremely broad. From young or relatively young viewers eager to see the film, more or less faux rock stars, representatives of the top echelons of the – political, quasi-political, media and institutional – Central Control, to a legion of paparazzi who obediently waited for their tasty bits, snapping persons not previously regarded as celebrities. All that formed a mix that was impressive but depressing at the same time.

The evening’s program was ripe with associations that no one would have invented better than the giggling mind of history. The first to appear on stage was Wojciech Waglewski – lit by whirling gobo lights, he delivered three songs, but their meaning was hard to guess: the few shreds of phrases produced the strange impression that what really mattered was the show – the beautiful big white guitar and the saxophonist cavorting around the stage. Next was Lech Janerka. He recalled his 1980s lyrics,which have retained at least some shreds of criticism. Then a big moment came – Lech invited Wojciech on stage and in a mood of brotherhood, to the audience’s applause, the two performed the former’s reggae-like Constitutions. After that hit song came passionate speeches and a catwalk for the event’s models: the film’s authors, its protagonists – the musicians, and all the sponsors. The compère, Marek Niedźwiedzki, offered the pitch that the movie would be successful with both those who remembered the times in question as well as with younger generations, and even with complete greenhorns. Then came the obligatory set of commercials, including one featuring the same Waglewski who had been on stage fifteen minutes before. The slogan of his visually sophisticated ad was that “everything will still be possible.” Unfortunately, this seems to be true.

Who teaches of grenades? / Who teaches you of peace? / Who tells you not to think? / Who tells you of aggression? / Who keeps criticising? / Who creates problems? / Who wants a new war? / Who tells you that we do?*

Beats of Freedom - Zew wolności

Beats of Freedom - Zew wolności

dir. Wojciech Słota and Leszek Gnoiński

Poland 2010The movie itself wreaked havoc in my imagination, memory and personal relationship with music. Although the original idea was highly promising and suggested that we would finally live to see a thorough analysis and appreciation of Polish independent music – as an intellectual and artistic phenomenon – nothing of the sort actually happened. The music and its message proved the least important part. What I did learn from the “documentary” was that the point of the whole thing was for Solidarity to win and that perhaps – who knows? – Lech Wałęsa listened to the most alternative bands and the Jarocin festival was like second home to some of the coolest Polish MPs who still, like Joschka Fischer, stand on the barricades, only slightly different ones these days.

I also learned that bands such as Lady Pank, Maanam or Budka Suflera were in fact as anti-regime, independent and subversive as Siekiera (a band utterly ignored in the film except for a brief shot of the vocalist), Dezerter or Brygada Kryzys. Those revelations were served by a British journalist who had come to Poland to discover independent music and confirm his own thesis that it had helped to overthrow communism and courteously provided musical accompaniment to the political changes. There were moments when subtle propaganda combined with archival footage that in itself made an incredibly strong impression. Robert Brylewski, in his teens, saying with utter, pristine seriousness that WE ARE AGAINST ALL THOSE WHO ARE AGAINST US. Thousands of people, craving freedom and music, occupying Jarocin, spike-haired punks contesting the SYSTEM. But what system are we talking about here? What was the subject of dissent? The surrounding reality – sure. But it also had various hues. The regime. Yes, but not only its designated representatives, also the conformism of its entourage and its subjects, society at large, who, for the most part, simply wanted to live decent and quiet lives. Passively adapting to the conditions at hand. Polish punk had been against this attitude from the very beginning. And the attitude has by no means gone with communism.

The film’s thesis is highly precarious. It suggests that since the collapse of People’s Poland and the unique Solidarity-led bid for independence we have been living in the freedom we so dearly yearned for, a truthful and luminous reality – a kind of NON-SYSTEM. That’s the greatest falsity the authors could have committed, an outright reversal of the fundamental ideals of the punk movement, always inherently distrustful and sceptical about STRUCTURES. As a result, the screen oozes tons of kitschy nostalgia: oh, but we were so cool then… oh, but the times were so great… Tomek Lipiński’s narration is backed up by, among others, Skiba, Janerka, Waglewski – speaking on the most independent and progressive Polish Radio 3 (note: the crucial Rozgłośnia Harcerska doesn’t get a single mention in the entire film), or Muniek Staszczyk who treats himself like a living legend. Some of the musicians have clearly lost their artistic credibility. What they sell today is toothless rebellion (sometimes in a glamorous version) and an image of themselves as the dinosaurs of Polish indie music.

It was symptomatic that none of the film’s protagonists invited to the gala tried to upset the complacency – it’d have been good to hear words such as Siekiera’s “Standing, I’m standing / dancing, I’m dancing / fighting, I’m fighting” from the glittering stage. Nothing, amnesia. And yet, remembering his contact with Solidarity, Dezerter’s Skandal told Krzysztof Grabowski that “There’s no one to talk to here. It’s a completely different world. These guys dig nothing. They don’t understand what we’re about, why we’re hollering .” I think that among those present in the Sala Kongresowa the level of understanding was very low, too. True, the film mentioned once that perhaps the communists’ silent permission for young people’s noisy follies was aimed at depoliticising the youth and diverting their attention from the Solidarity movement, but this theme wasn't explored. The only statements we got were coquettish comments about time that flows and that in the film everyone looks better than today. Which reminds you of the sad truth that it’s sometimes better to leave the stage at the peak of your career or die young so that the myth and message can live on.

Side Effects – what is it for?

We meekly accept the presumption that BOUNDARIES DEFINE SETS. Does a “stone rejected by the builders become a cornerstone” or turn into dust? On the assembly line of important, first class, de luxe ideas, hybrid entities are treated as defects, and they are accompanied by phenomena of unspecified origin. They all end up in a large waste container. Lying there and together forming a mess are unselected items from the Culture department labelled independent, hidden, mass, breakthrough/broken through, street. The waste products we generate say too much about us, therefore they should be recognised as worthy of observation and as a step on the path towards fulfilling a utopian, beautifully impossible dream: that of comprehensively cognising and understanding the world. Side Effects is a place prepared for the effects of the mass-scale, deductions from materialism, conclusions/marginalities of existence, added values – are they art (since they’re called that?) or perhaps a market product or kitsch in the faux feathers of loftiness? Such events and phenomena deserve attention and transdisciplinary reflection. It is sometimes worth lookingat the background processes and searching for borderline situations that offer formative potential. Like oxygen in photosynthesis.

The film’s authors made sure to ignore the bleak aspects of the era – decline, despair, distrust. Phenomena that were the milestones of independent music – such as the aforementioned Skandal, Dezerter’s first vocalist (who didn’t live to see the release of the band’s debut record), or bands like Siekiera, which influenced an entire generation or more, Armia or KSU – are completely missing from the film. Obviously, they weren’t in tune with the authors’ issue. One of the latter (Leszek Gnoiński) so described his artistic goal: “This is a story that is to be told by certain people, through certain events, to be comprehensible, non-hermetic, fun to watch. Because it’s supposed to be entertaining.” Some might say that you can’t have everything in a 70-minute film. That’s probably true, but in this case the story doesn’t hold ground – pretending to be a documentary, it presents history distorted in the mirror of a pro-system fairy tale about freedom.

Who sets the fashions? / Who is it that guides you? / Who feeds you with nonsense? / Who tells you all the lies? / Who destroys Afghanistan? / Who shoots in Salvador? / Who is always smiling? / Who is omnipotent?*

In a relatively recent documentary Idź pod prąd (Go Against the Grain), Tomasz Lipiński talked about Brygada Kryzys’s planned show at Solidarity’s True Song Festival at the Olivia venue in Gdańsk in 1981: “To our surprise, we saw there the same show-biz industry smooth operators who had been sweetie-sweetie with the comrades. They appeared there as heralds of freedom and that gave us something to think about.” It’s hard to believe that things have changed so radically over the last two years and the same man has unexpectedly changed his mind. In the video clip shown after the film, everyone seemed complacent. Everyone also commented sentimentally on the old days – including Jolanta Kwaśniewska who said, “This is partly a history of every one of us. Even all those who didn’t have the chance to personally participate in the events of the 1970s and 1980s. Everyone probably feels that just by listening to this music we can feel a little better.” From the logical point of view, this may not have to be a false statement. It’s indeed part of the history of every one of us – but for each one of us in a slightly different way.

It was really nasty to watch how meticulously the attitude of dissent had been eliminated from the film and the whole anti-system phenomenon had been repackaged by Central Control and used for its own purpose. After leaving that cinema/circus I felt that one of the last strongholds of independence, dissent and truth had been professionally appropriated and exploited. The real opponents of hypocrisy and servility have been replaced by double-dealers, feigning attitudes they have nothing in common with. Perhaps we’ll soon see one of them lending their name to a kinder-punk clothing line, a safety pin stuck to their ear using hypoallergenic glue.

Even though I was born in 1982, when Siekiera was only being formed and the light rock Lady Pank had only begun playing their first gigs in Warsaw (to then gain momentum and shine at the regime-sponsored festivals in Opole and Sopot), I award myself the right to completely reject the manipulation and shallowness – the devices this film tries to buy me with. It has nothing to do with the kind of courageous, independent statements we have come to associate with documentary filmmaking. Instead, I feel like watching again Maciej Drygas’s Hear My Cry, a documentary about courage and a truly noble, rebellious attitude, and Marcel Łoziński’s Workshop Exercises, which, in a concise and metaphorical manner, shows the basic techniques of propaganda manipulation. These cinematic readings may prove of greater benefit to young people and instil in them a truer gene of rebelliousness and autonomy than Beats of Freedom – a high-budget quasi-documentary export product. It’ll be interesting to see how it fares on the international market. Central Control will save us.

* it’s the same people.

(Dezerter, Who?)

translated by Marcin Wawrzyńczak