“Each film is my last,” proclaimed Ingmar Bergman in a 1959 text that is regarded not only as the director’s comment on his own method, but also, and above all, one of the most important manifestos of avant-garde cinema. Even if it is unconscious and done in good faith (which is by no means mutually exclusive) – Andrzej Wajda seems to have been saying for quite a long time now that each film is his greatest one. And in no way is this the result of a lack of modesty on Wajda’s part (modesty being one thing Wajda surely doesn’t lack), nor excessive self-confidence or over-ambitiousness (which would be understandable in the case of such an outsanding artist) but rather of a peculiarly construed sense of responsibility. Responsibility for Polish cinema. Responsibility for history. Responsibility for the moral and spiritual condition of the Polish people.

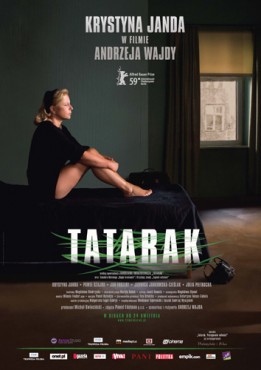

Tatarak (Sweet rush), dir. Andrzej Wajda,

Tatarak (Sweet rush), dir. Andrzej Wajda,

Poland 2009Is there a point in holding this against him? Isn’t this what we expect from one of Poland’s greatest filmmakers? Shouldn’t we be only grateful to him for the consistency with which, for over fifty years now, he has conveyed in his films a specific vision of Polishness, on the one hand, and a certain artistic myth, on the other? Can a filmmaker who laid the foundations of the Polish film school in the 1950s and in the 1970s contributed to the development of “cinema of moral anxiety”, all the time remaining faithful to the tradition of avant-garde film, be criticised for continuing to feel responsible for Polish culture, and film culture in particular? And finally, doesn’t an artist of this caliber have the right to make mistakes? Mistakes made by the greatest filmmakers – Antonioni, Fellini, Bergman, to mention but those whose artistic paths are as representative for European film history as his.

The main problem however is that Wajda himself doesn’t give himself this right. I don’t mean his declarations, as he is perfectly aware that not all of his films (not only those from recent years, but earlier ones as well) are equally good. I mean what his films say and demonstrate, I mean the “pressure of infallibility” that accompanies the premiere of any Wajda movie. His sense of responsibility – precious in itself, especially in the case of a filmmaker, as film remains a particularly influential and suggestive medium – turns Andrzej Wajda almost into an Atlas of Polish cinema. On his shoulders rest not only all of Poland’s film production, of course, but that fragment of it that is supposed to abound in the greatest works, those tackling issues of the utmost importance.

Thus, when making Pan Tadeusz or Katyń, Wajda rather consciously adopted a collective perspective rather than his own – perhaps assuming that the two were still identical. He decided to take up issues that automatically, as it were, entangle any film in a nationwide debate. Of course, Wajda has immense experience in this field. Suffice it to mention Ashes and Diamonds or Man of Marble to decide that the most characteristic aspect of Wajda’s art is his unique ability to tackle “generational” issues. His latest works however show clearly that the practice can with time (or simply in certain historical circumstances) result in a dangerous melting or merging with the collective. The same sense of responsibility that in his earlier films allowed Wajda to so successfully trigger off debates on the most important social or historical issues prevents him now from “going wrong”, from reaching for subjects that would be smaller, marginal, his own.

It would seem that Wajda’s latest film is precisely an attempt to resolve this peculiar deadlock, to reject the thankless role of the mainstay of Polish national cinema and return to quieter, more personal work. Sweet Rush (Tatarak) is another in the director’s oeuvre – after Brzezina and Panny z Wilka – adaptation of Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz’s prose. It is also a return to self-referential cinema (of which the 1968 Wszystko na sprzedaż remains the most splendid example), focused, at least in the author’s intention, on an analysis of the creative process. It marks Wajda’s return to working with Krystyna Janda, who appears in a double role in this film, playing the protagonist of the Iwaszkiewicz story and herself. Finally, it is a return to two most cinematic but also most Wajdian motifs – love and death.

Ultimately though, Sweet Rush is above all a paradoxical film, full of irritating self-contradictions unjustified by the chosen narrational and formal solutions. An adaptation of Iwaszkiewicz that almost completely misses the original’s mood and sensuality. Sure, the story itself is mentioned often and in various ways, but Wajda no longer searches – as was the case in, for instance, Panny z Wilka – for aesthetical solutions that would correspond with specific phrases in the literary original. Instead, he reaches for images, tautological towards the dialogue, filled with digitality and visual pathos, that, he probably believes, respond to the contemporary viewer’s sensibilities. A self-reflecting work that lacks a sober perspective on the directors’s own artistic views (otherwise characteristic for the formula), with no concentration, no examination of the film’s very constructional basis. Instead, the director mechanically recycles solutions commonly associated with his style (like in the film’s undoubtedly worst scene, set in the room of the main protagonist’s sons, who had died in the Warsaw Uprising), bringing himself dangerously close to the verge of pretentiousness.

Sweet Rush has been promoted as a modest film in which the director confides his existential anxieties to the viewer while allowing his actress a highly personal performance (though admittedly a checked one) in which she can work through the trauma following her husband’s death. Love and death intertwine in this film on many levels – sometimes in quite successful or moving ways – but what good does it do if Wajda never goes beyond the most obvious clichés and most stereotypical emotions. The themes of love and death are explored in this film in a sense that here we face issues of highest importance and, above all, issues and emotions shared by us all. In a deliberately low-key film, unlike in the great productions, there is no explanation for the lack of emotional subtlety, gradation of tensions, actual self-exposition and highlighting of truly personal issues. One can hardly believe that Wajda perceives the Eros-Thanatos relationship solely in mythological terms, ignoring all that is small, unimpressive, average or shallow in love and death.

Thus Sweet Rush remains a flawless work. A great work. But one can’t help wondering whether Andrzej Wajda will ever try to make a film yet or whether he’ll spend the rest of his life creating great cinema.

translated by Marcin Wawrzyńczak