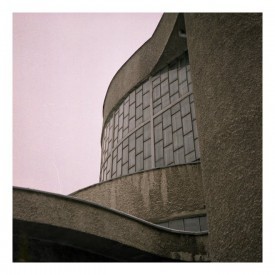

Undulated concrete. Grey facades. The sky, although bit brighter, is gray too. All that enclosed within a square frame. Several frames – one beneath the other. It’s the same building all along, photographed from different perspectives.

What can’t be seen is that it’s the church at Wrocław’s St. Lawrence Cemetery which the photographs’ author, Paweł Starzec, noticed for the first time only recently, walking around the place with his girlfriend looking for the grave of Rafał Wojaczek, the poet. Paweł likes this kind of architecture. Paweł is a secondary-school student in Wrocław. He takes photographs – several a day – that, when put together, form a series. Series of squares, as he usually uses a medium-format Bronica. He says it’s easiest for him to think about a photo in terms of a square because of the interesting possibilities it offers in terms of composition. He scans the exposed films and posts selected pictures on his blog. photo: Paweł Starzec19/20. The bright sun casts on the pale wall the distinct shape of a rhombus in such a way that it seems to glow. The room next door is veiled in soft greyness, illuminated by sunlight piercing through a patterned curtain. 21/22. A black tailor’s mannequin wearing blue beads stands in the corner, where the white wall meets the white wardrobe door. Beside, on a bright-blue wall, an orange poster of the band Kult. The bed beneath is covered with square-pattern Ikea sheets.

photo: Paweł Starzec19/20. The bright sun casts on the pale wall the distinct shape of a rhombus in such a way that it seems to glow. The room next door is veiled in soft greyness, illuminated by sunlight piercing through a patterned curtain. 21/22. A black tailor’s mannequin wearing blue beads stands in the corner, where the white wall meets the white wardrobe door. Beside, on a bright-blue wall, an orange poster of the band Kult. The bed beneath is covered with square-pattern Ikea sheets.

The latter room belongs to a close friend of Paweł. Other rooms may be those of other friends or acquaintances but they may also be rooms of strangers he’s never met. Paweł has been photographing interiors for a year now. His friends, the closest ones, take part in the project, making their rooms available to him. Paweł prefers to photograph interiors and spaces than people. But the people close to him know exactly how to read these pictures. For them, Paweł’s blog is a collection of shared memories in which they recognize the places they’ve gone for a beer, on trips, where they sat and chatted, places they passed on their way to the cinema. 19/20, photo: Paweł StarzecFor them, the series Paweł creates are a knot of shared memories that tie their group together. His blog is a scrollable and clickable archive of social events and intimate emotions.

19/20, photo: Paweł StarzecFor them, the series Paweł creates are a knot of shared memories that tie their group together. His blog is a scrollable and clickable archive of social events and intimate emotions.

Series organise life, helping to integrate quivering and fragmented moments into a single whole, with a beginning and an end, which, in times that Zygmunt Bauman calls ‘liquid,’ is something of particularly great value. “Time is compost,” writes Jakub Żulczyk in his latest novel. “Events are scattered like scraps of paper. Index cards.” Żulczyk writes about eighteen-year-olds – Paweł’s peers. In his novel, the protagonists live in a “music video, in a short story told backwards, in a meat roll of soap operas, scrambled events.” Time has gotten mixed up. 21/22, fot. Paweł StarzecSoap operas, evenly measuring time for the generation of our parents, with the title sequence of the Polish afternoon series Klan reminding them to put the potatoes on to boil and the M jak miłość jingle heralding the longed-for evening rest, have ceased to play the additional functions now that they can be downloaded or watched online. They no longer measure out time – instead, you can get lost in them by watching a dozen episodes in a single session. Time has accelerated.

21/22, fot. Paweł StarzecSoap operas, evenly measuring time for the generation of our parents, with the title sequence of the Polish afternoon series Klan reminding them to put the potatoes on to boil and the M jak miłość jingle heralding the longed-for evening rest, have ceased to play the additional functions now that they can be downloaded or watched online. They no longer measure out time – instead, you can get lost in them by watching a dozen episodes in a single session. Time has accelerated.

We’re inventing ever new ways of organising time, bending, arresting, and manipulating it. Photographic series – whether professional, created as artistic projects, or by amateurs – made intuitively, as it were, unconsciously – all of them are operations performed on time. “Through photographs,” Susan Sontag writes, “the world becomes a series of unrelated, free-standing particles; and history, past and present, a set of anecdotes and faits divers.” In a photographic series, the fragmented is reintegrated. It’s true that photography makes it possible to fragment the world – to arbitrarily select some images while rejecting others, it captures only some in its frame. However, you can then rearrange the bits into a new whole.

Paweł arranges them into series that seem to lock time, immobilize reality by catching it doing something banal and prosaic – a pothole, an accidental juxtaposition of colors, a reflection of the sun, the steady rhythm of architectural elements – while in fact they measure time out. By marking the end of moment, they set the beginning of another.

The seemingly static catalog of the photographic series by Bernd and Hilla Becher is in fact a dynamic creation. These images of industrial buildings are, as their authors claimed, documentary in nature. Their series of photographs – always identically composed, showing the same kinds of objects (reservoirs, factory smokestacks) always from the same perspective, seem to freeze time. But in reality they are a significant gesture of the photographing hand and eye. “There’s no such thing as an innocent eye,” as the title of another photographic series by Wojciech Wilczyk’s tells us. The eye and the hand not only compose the shot and release the shutter, but they also select and juxtapose. The decision what should be placed next to what isn’t neutral and goes beyond the documentary.

Travestying Wilczyk, one feels like saying that there is no such thing as documentary photography. His series of pictures shows buildings that used to be synagogues. Polychromatic, in natural light – sometimes in bright sunlight, sometimes under a clouded sky. Simple compositions, showing all that has built up with time, such as banners, the letters coming off, announcing a wallpaper sale, uneven curbs, traffic signs affixed to weak wall plaster, and sometimes windows boarded up with planks. All that is somewhat impassionate but, at the same time, in a way, brutally frozen and confronted.

“Juxtaposition lets me say what can’t be expressed with a single picture,” says Konrad Pustoła. I particularly like his series Unfinished Houses (2005). Just compare the difference between seeing the pictures separately, and in sets. A juxtaposition reveals the process. A series allows you to talk about a phenomenon that is stretched out in time or space. What more, it produces a picture of entire phenomena that otherwise wouldn’t be visible. Through juxtaposition, a single photograph not only gains context so that more can be read from it but also becomes an integral part of another, larger whole. The result is qualitatively different. The series can’t be reduced to the sum of its parts. Unfinished Houses 2005, fot. Konrad PustołaLooking at only one or two pictures from Eric Tabuchi’s Alphabet Truck series won’t let us grasp the whole. The series of images of the backs of trucks rambling down the highway arranges itself into an alphabet. Quite literally. The cycle begins with the image of a tarpaulin marked A and ends with a Z.

Unfinished Houses 2005, fot. Konrad PustołaLooking at only one or two pictures from Eric Tabuchi’s Alphabet Truck series won’t let us grasp the whole. The series of images of the backs of trucks rambling down the highway arranges itself into an alphabet. Quite literally. The cycle begins with the image of a tarpaulin marked A and ends with a Z.

On its own, each of the trucks here seems frozen in movement but shown all together and held together by the bookends of the alphabet, they evoke the classic motif of the road. Another of Tabuchi’s projects also deals with the road and alludes to the famous series Twenty six Gasoline Stations. Ed Ruscha photographed gas stations alongside the legendary Route 66. In the book, which is a purely visual document of the trip, black-and-white pictures of the stations are arranged in almost the same order in which they appear in reality. Tabuchi’s series of images of abandoned gas stations, even though these are realistic photographs, gives the impression of an abstract painting. This is no longer mere photography, this is pure painting. The colors are muted: beneath the pale sky dominate rust-eaten navy blues, dirty reds and yellowed grass greens. The constructions of the slender supports and straight roofs, the rectangular pavilions and square windows form a geometric grid. The viewer’s eye can easily imagine them as the block in the computer game Tetris. Unfinished Houses 2005, fot. Konrad PustołaIdris Khan’s project, which achieves interesting effects by superimposing several Becher photographs of the same type on each other, is a kind of visual, but also conceptual game. Not only because there is unique value to all procedures that conceptually transgress the boundaries of photography and go beyond strictly photographic practices, forcing photographers to stop “just taking pictures” and start interacting with photographs instead. Khan proceeded literally – he selected pictures by the Bechers, several of each kind, and superimposed them upon each other. He thus obtained an image that presents the object in varying degrees of intensity. Wherever the greatest number of shapes and lines converge, there the photograph is darkest. Sparsely arranged elements are brighter, while those that appear by themselves upon the white background are nearly indiscernible. The superimposition seems to bring out the essence of each of the objects. Khan’s act here complements the Bechers’ typologies by synthesising them to the most common case. Perhaps it’s an artistic representation of what statisticians show in graphs as normal distribution.

Unfinished Houses 2005, fot. Konrad PustołaIdris Khan’s project, which achieves interesting effects by superimposing several Becher photographs of the same type on each other, is a kind of visual, but also conceptual game. Not only because there is unique value to all procedures that conceptually transgress the boundaries of photography and go beyond strictly photographic practices, forcing photographers to stop “just taking pictures” and start interacting with photographs instead. Khan proceeded literally – he selected pictures by the Bechers, several of each kind, and superimposed them upon each other. He thus obtained an image that presents the object in varying degrees of intensity. Wherever the greatest number of shapes and lines converge, there the photograph is darkest. Sparsely arranged elements are brighter, while those that appear by themselves upon the white background are nearly indiscernible. The superimposition seems to bring out the essence of each of the objects. Khan’s act here complements the Bechers’ typologies by synthesising them to the most common case. Perhaps it’s an artistic representation of what statisticians show in graphs as normal distribution. Unfinished Houses 2005, fot. Konrad PustołaThe series is a set of realistic photographs that, by means of juxtaposition, transgress their boundaries. Meaning sparks at the connection points, demanding interpretation. Each picture, regarded separately, is static. Boring. Juxtaposed with others, or, in the extreme case, superimposed upon them, it obtains new meanings. The seemingly simplest juxtapositions, that is, inventories, like uninspired catalogues of objects of the same category, aren’t limited to what Ed Ruscha or the Bechers wanted to attribute to them when they claimed, separately though unanimously, that series are no more than collections of facts. Realism is encoded in photography but photography’s relationship with reality is highly complex. “… photographic realism can be … defined not as what is ‘really’ there but as what I ‘really’ perceive,” Susan Sontag writes. If an inventory is a document of anything, it’s of the gaze rather than of reality or facts.

Unfinished Houses 2005, fot. Konrad PustołaThe series is a set of realistic photographs that, by means of juxtaposition, transgress their boundaries. Meaning sparks at the connection points, demanding interpretation. Each picture, regarded separately, is static. Boring. Juxtaposed with others, or, in the extreme case, superimposed upon them, it obtains new meanings. The seemingly simplest juxtapositions, that is, inventories, like uninspired catalogues of objects of the same category, aren’t limited to what Ed Ruscha or the Bechers wanted to attribute to them when they claimed, separately though unanimously, that series are no more than collections of facts. Realism is encoded in photography but photography’s relationship with reality is highly complex. “… photographic realism can be … defined not as what is ‘really’ there but as what I ‘really’ perceive,” Susan Sontag writes. If an inventory is a document of anything, it’s of the gaze rather than of reality or facts.

Sense and meaning emerge not only from selection but also, and above all, from the mode of representation. The white walls of a room and on them large prints over a meter in high, and one side of the room covered in pictures of boys and young men of various ages and dressed in a range of different outfits – all photographed in the same way, against a white background.

On the opposite wall, photographs of rooms. All kinds of rooms: large, small, (usually) untidy. Scattered papers and dumb-bells, yesterday’s T-shirt, a swivel chair next to a desk. It’s a project by Paweł Bownik called Gamers. The pictures hang next to each other, in an even row, and the gaze easily moves from one to another. The Bechers’ photos were displayed differently. Pictures of the same type were placed next to each other, forming rectangles. You look at them as you would at abstract paintings. A white background. The photographs are posted online as well. A line of images on a white background – the edges adjoining, so that it’s sometimes hard to tell where one picture ends and the next one begins. The images go on like a story, forcing you to keep scrolling. They can be presented horizontally or vertically. It’s hard to say whether scrolling images on websites is more like browsing through a book or like watching a movie. The division between a book and photographs or film has become blurry. Are the hundreds of images, blinking at us page after page like film frames, still a photographic presentation? Here we see how Noah is changing, how his hair is growing, how he grows a beard and how, suddenly, he shaves it, how the oval of his face changes, how he dresses differently day after day. We see the flow of time. Six years of life in accelerated motion in six minutes on YouTube. He photographed himself every day strating in January 2000 (YouTube didn’t exist back then). Noah is another version of Auggie Wren, the main character, played by Harvey Keitel in Smoke, who takes a picture of the same fragment of reality at exactly 8 a.m. every day. Auggie Wren photographs a street corner in Brooklyn, Noah – his own face.

Photography is a form of conquering the world, as Sontag writes. Series are a form of temporalisation, we may add, colonisation of time. Photographic orders – be it artistic series, documentary cycles, family albums, blog illustrations or photos compiled and edited into YouTube videos – are a way of making coherent a world that we experience as chaotic and liquid.

The author would like to thank Konrad Pustoła for a rewarding conversation and for the permission to publish his photographs. The author would also like to thank Paweł Starzec for the permission to use his pictures.

translated by Marcin Wawrzyńczak