In 2009 Joanna Bator’s Sandy Hill was published – an extraordinary novel about the birth and fall of socialist society where the principle of sameness reigned. Cloudalia, a continuation of that story, describes a world where life blossoms thanks to differences.

Sandy Hill ended with a scene in which Dominika Chmura (Cloud), freshly graduated from secondary school, is in a car accident. Dominika is the incarnation of otherness: Jewish and Russian blood runs through her, she has chosen a lesbian for a friend and, on top of that, has an affair with a young priest.

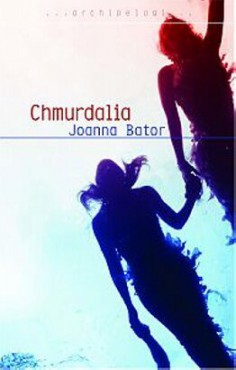

Chmurdalia, Joanna Bator,

Chmurdalia, Joanna Bator,

WAB Publishing House, April 2010After the accident Dominika spends months in a hospital in Germany – first in a coma, then in rehabilitation. On leaving the hospital she decides not to return to Poland. From now on she wanders the earth, prompted by a vague desire to roam. In Germany she works in a tinned fruit factory; in the USA she is employed as a reader reading books to an elderly woman; in England she serves drinks in a restaurant. Everywhere she meets people, offering a simple yet unusual gift – readiness to listen to someone else’s story. When she arrives in a new place people think they already know her. When she departs she leaves behind a kindly longing.

The novel, though, is not carried by chronology but by the rules of a saga. Characters, however, appear not because they belong to the family but because of fortuitous meetings. The novel has, therefore, the structure of a genealogical bush – an entanglement more like gossip than a chronicle. The narrator, like a medium, passes the voice over to various storytellers: someone’s story takes us back to the beginning of the 19th century when Napoleon rode across Poland and Black Venus was brought to Paris from Africa to be shown as a curiosity in salons and circuses; someone else tells the story of life in Kamieńsko, a small Polish village where, before the second world war, two strange spinsters known as Aunties Tea kept Napoleon’s chamber pot; we hear the complaints of Dominika’s mother, a widow, slowly gathering strength to introduce changes into her life. People’s fates, like branches, touch momentarily so as to go in different directions, then unexpectedly they join. These meanderings of the genealogical bush show that no-one is a separate story and that nobody has merely one place ascribed to them on earth.

translated by Danusia Stok

The above review was originally published on the Book Institute's website.

Joanna Bator (b.1968) writer, journalist, university lecturer. Sandy Hill is soon to appear in Hungarian and German translations.