Whatever we might write about Mariusz Grzegorzek’s new film today has surely already been written because this one of the best recent Polish movies waited two years for theater distribution since its premiere at the Gdynia Film Festival. In fact, this is becoming a peculiar tradition – a similar fate was not so long ago experienced by Andrzej Barański’s A Few People, a Little Time. This is bad, of course, but even if I Am Yours had spent five years in limbo, it would not have lost much of its freshness.

The movie is a small cross-section of the contemporary world: the script, based on a play by Judith Thompson, brings together people from different social and cultural orders. Marta and her husband live a beautiful life – in a big, clean house in a gated community. Guarding the place is Artur, who has just been released from prison. After hours, the hot-tempered macho plays computer games in his sleazy apartment and tries to loosen his umbilical cord somewhat – worried by his unhygienic lifestyle, his mother is trying to drag him back home (“You’d have your board and keep”).

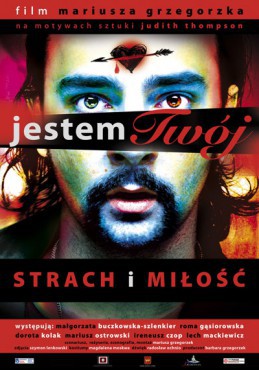

Jestem twój, dir. Mariusz Grzegorzek,

Jestem twój, dir. Mariusz Grzegorzek,

Poland 2009In the pretty house in the gated community – even though it is so tastefully furnished and so functional – something is still going wrong after hours. The neat body of doctor Marta seems to host two personalities, at least one of which wants to tear apart her husband, a polite professional from a glass-and-steel office building. Marta’s fits of fury and hysteria, which look like satanic obsession, result in her parting with her husband and having wild sex with Artur. It seems that the two have found each other, that some grim inner burden connects them. But before cultural difference-transgressing love can develop, an unwanted pregnancy steps in, which turns out to be a problem on the scale of the 19th-century bourgeois drama. The devilish instigations are gone, all is left is a crude misalliance.

Grzegorzek’s film is, of course, a story about class conflict, about a clash between those who have (money, prestige, comfort, knowledge) and those who do not. But it shows it, at last, as a tragedy rather than as a farcical skirmish between grotesque moustache wearers and Miłosz-reading, emancipated descendants of the flower children. There is no duel here between the director’s mouthpiece and stupid society. No one pats the viewer on the back, assuring them they belong to the enlightened club that shows its superiority precisely by deriding common obscurantism. Each of the characters is searching for, and cannot find, the same thing: love, solace, something really meaningful. The means they use to obtain this are different and not very sophisticated: violence, sex, and venomous motherly overprotectiveness.

Irrespective of how they express it, the pain felt by the characters is the same, their eyes are filled with the same fear. Their longings – irrespective of their (income) status – bespeak of the same desperation, the same pathos. Alina, Marta’s emotionally battered sister, has an image of happiness embodied in a kitschy song. Artur’s mother holds on to a petty-bourgeois sense of dignity and propriety. The others, having nothing to hold on to, grope around, banging, like Marta, their heads against the wall. Behind the wall, under the surface of quiet normal life, pulsates unease, calling for a shape, a form, and forcing one to keep reopening old wounds. When Marta and Alicja talk about the “dark” thing hidden deep in Marta’s psyche, the roots of which go back perhaps to their own childhood, both turn into small girls telling each other about an evil witch from the dark forest.

I Am Yours has some superb performances. More than that: it is a genuine display of brilliant acting and I cannot think of a Polish movie played so evenly and with such a sense of the border, such an ability of balancing on it. In fact, it is not only the actors who are balancing but also the director who changes the tone every now and then: is it a farce, a social drama or perhaps a horror? During the unbearable and, at the same time, delightful screening at the Nowe Horyzonty festival in Wrocław, the audience burst out laughing at the most dramatic and moving moments. Probably out of desperation and consternation. The authors do not offer the viewer a breather here, no possibility of adopting a psychologically comfortable position. At first, you even start suspecting that a horned devil or a murderous alien is going to break out of the main character’s breast. But, again, people manage splendidly.