“I don’t know what’s going to happen. I’ll just sit down with my friend, we’ll talk, and see where it takes us.” This part-confession/part-announcement opens the film that Bouzereau shot during Polanski’s house arrest between 2009 and 2010. It comes out of the mouth of Andrew Braunsberg – a friend of the director who travels to visit Polański in his Swiss home and question him about the happiest moments of his life. And so it is: two guys sit in front of a camera and reminisce, while the director, Laurent Bouzereau, intersperses the conversation with bits of war footage, television programs, private photographs. But the experiment evaporates leaving no trace, and the assurance we were left with in the beginning seems unnecessary and fake, because both its form and the direction that the narrative is heading is less than surprising.

This movie corrupts the critical viewer. As a documentary, it’s extremely biased, inconsistent, and at times terribly weak and superficial. But fans of Polański’s work will not consider the viewing a waste of time. The director’s life resembles a story that is at once horror and fairy tale, so it’s not hard to imagine how interesting it might be. But people who know Polański’s biography, who read his memoirs, and who saw Marina Zenovich’s Roman Polański: Wanted and Desired will simply be disappointed. Bouzereau tears through the recognisable moments in the career and personal life of Chinatown’s director, treating them as a sort of “best of”.

The problem lies with Andrew Braunsberg, who looks barely interested in mining Polański for something that hasn’t been said and consumed before by the media. He gets excited by sensationalist episodes in his biography and during the conversation he’s more of a fan than a friend, making Polański uncomfortable. Braunsberg does not let him stray from the biography path, which makes the movie too similar to a late-night talk show. He offers the answers he wants to hear and is often only waiting for some sort of confirmation (constantly uttering “that’s right”). He suggests emotions, expecting an explosion of feelings and tears.

The interesting notion of using this peculiar stasis Polański found himself in to extract from him something more than tabloid-worthy bits was subverted already in the conceptual phase. Placing the conversation in the context of Polański’s arrest was an obviously biased move and it killed the private (or even intimate) character of the meeting. The filmmakers give Polański a voice, enable him to tell his side of the story. But they refrain from asking the tough questions, they slide over the uncomfortable issues. And thus they completely unnecessarily transform the movie into a sort of statement of the defendant.

Roman Polański, dir. Laurent Bouzereau,

Roman Polański, dir. Laurent Bouzereau,

Great Britain 2011, in cinemas since May 2012 Immediately after mentioning the infamous scandal (sex with a minor), the filmmakers ask about memories of the ghetto, immediately reducing Polański’s legal trouble to nothing more than an unfortunate incident. Braunsberg and Bouzereau magnanimously exonerate Polański, judging their subject on account of his tragic life and great talent alone. They exhibit the same troubling arrogance that characterised the media’s attempts at passing moral judgments about Polański’s actions. Even the director himself does not use the film to cast himself as the victim. He elaborates on his experiences in a way that suggest he’s very aware of the duality of life. “Your life was filled with so many tragedies,” sighs Braunsberg to which Polański quickly retorts: “Maybe so, but there were also triumphs and lots of joy.”

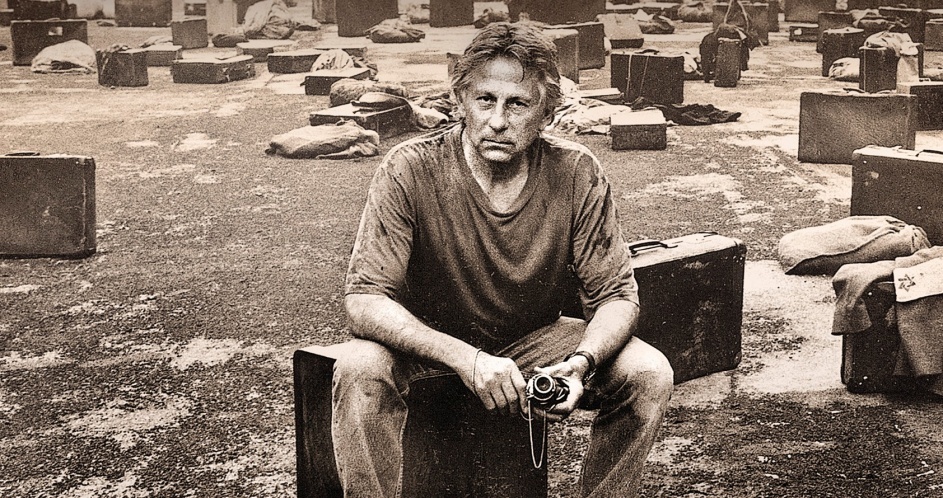

The part of the movie that deals with Polański’s childhood is easily the most interesting. That period of his life is least exploited by both the media and the director himself, who (The Pianist being the sole exception) generally stays away from war-related themes, and whose work was able to successfully evade reality. Here, he evades his conversation partner, discovering memories still so rich with emotion that it seems to surprise Polański himself. He delivers context-less scenes in a way that resembles his direction work, but at the same time he looks like he’s watching these same vignettes from the audience’s perspective. Polański concentrates not on events themselves, but on the way he experienced them. The less spectacular the events were, the more impressive the telling is.

It’s surprising to see an artist surrounded by so much drama and shrouded in such mystery display the openness of a little boy when he talks about a teenager’s perspective on the war in the familiar surroundings of his own home. He imitates the roar of airplanes flying over the forest, he drops on all fours to illustrate another memory. The movie is worth seeing in the cinema precisely because of these stories, like the one about constructing a crystal radio receiver, and not because we’ll be able to see the director cry. The later parts of the movie pick up speed, because the filmmakers wanted to cram as much material into it as they possibly could. Unfortunately, this results in the flick becoming increasingly superficial, while the filmmakers seem to feel that they need to defend their subject whenever a new controversy pops up around him.

The effect is paradoxical enough that it could have been planned by the director of Cul-de-sac himself. The filmmakers failed trying to defend Polański. The movie’s greatest redeeming quality is Polański himself.

translated by Jan Szelągiewicz