The sheer numbers describing this exhibition: the many hours needed to view the works of the over 200 women and men artists presented, more then 400 works on display, several years spent on preparing and conducting field research in 24 countries, 60,000 visitors of the original show in Vienna, all this makes you feel you are confronting a colossus.

As curator Bojana Pejić stresses in her essay Proletarians of All Countries, Who Washes Your Socks? The exhibition didn’t aspire to create any complete narrative. Rather, it’s a research project explaining how hierarchies such as gender are constructed and legitimised. Where the picture is surprisingly coherent is in how the body continues to be exploited as a territory of conflicts, appropriations and spectacles, a territory that needs to be constantly rediscovered.

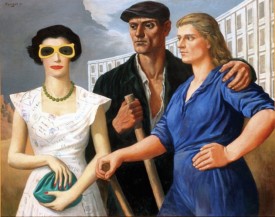

The exhibition’s first part belies the ideological correctness about gender equality in the socialist society. Dressed in overalls, housecoats, aprons and work uniforms, the bodies here have been written off, treated as material that can be colonised and moulded to serve predefined needs. What is promoted is, above all, a peculiarly construed naturalness, physical stamina, health and simplicity consistent with the ideal of the new individual. The inertia of the muscular bodies, moved by the rhythm of working for the common good, represents perfect material for propagandistic schemes. The eyes of the women in the portraits shown in the exhibition are empty, waiting. New content can be easily inscribed in them. There’s no need of revolt against the body’s natural duties: giving birth, caring for the family, working, mutual help. The system, based on the simplicity of the aspirations and goals set for the citizen, functions smoothly, regulating everything. Man, machine and nature are synchronised in harmonious operation. Among the several dozen paintings showing lively women at work, one can find numerous exceptions from, or counter-models for, the officially promoted image. Pictures full of melancholy and alienation. A photograph by Helga Paris shows a woman who, according to the title, is a textile factory worker. She is wearing a flowered housecoat that hugs her zaftig figure. Her left hand rests flirtatiously on the railing. She looks at the viewer seriously. She seems aware of her beauty, hidden under her paleness, traces of fatigue and the workplace uniform. The icon of this part of the show is Wojciech Fangor’s Figures, where sexual desire and the body’s eroticisation are inscribed into the figure of an elegant young woman, her appearance clearly alluding to the capitalist world, and opposed to a heavyset worker couple glancing at her with both aversion and envy.

Uncovering

Wojciech Fangor, Persons, Poland 1950,

Wojciech Fangor, Persons, Poland 1950,

courtesy of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, photo:

Wojciech FangorIn their protests, the US collective Guerrilla Girls demanded that the principle that a woman could find herself in a museum only if she was naked be abandoned. In the Zachęta exhibition, in the part titled Negotiating Personal Spaces, this demand becomes less imperative. Most of the artists here resort to self-portrait, voluntarily exposing their nakedness to the viewer’s gaze. This exposition of the naked body as artistic material is tantamount to unblocking the self, negating the culturally-imposed constraints, transgressing one’s sense of shame. The existential dimension of corporeal self-understanding in the era’s popular performance-art format was a reaction to the suppression of individuality in social life. In the context of the many projects presented here dealing with the issue of voyeurism, the gaze as an instrument of power ceases to be transparent particularly in Sanja Iveković’s Triangle, a performance carried out in 1979 in Zagreb during Josip Broz Tito’s visit to the city. The artist appeared on the balcony of her apartment which faced the main street where the presidential motorcade was passing, sipped whisky, read a book and simulated masturbation. Her presence was noticed by a secret service agent scanning the area through binoculars from a nearby roof. As Piotr Piotrowski puts it, “The act of masturbation, performed during a political spectacle, or, in other words, the act of manifesting female sexuality in a situation when the body should have been subjected to a general discipline governing public political behaviour, dramatically breached the decorum of roles assigned by the regime to its male and female citizens.” Iveković’s action took place in a semi-private, semi-public space. Breaching it revealed the fact that no boundary between them existed, that the system was all-encompassing. The body’s role is pre-defined. Neither private space nor the body are able to provide you with a sense of freedom. When no one sees you, self-surveillance begins. The policeman from outside sneaks in and installs himself inside.

Seeing

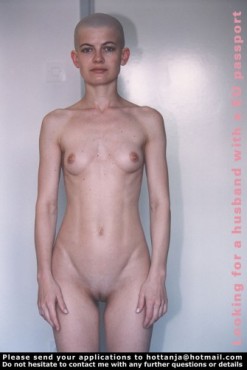

Tanja Ostojic, I'm looking for

Tanja Ostojic, I'm looking for

a husband with an EU passport,

Serbia 2000-2005, courtesy of the artist,

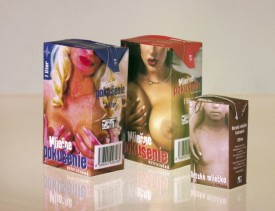

photo: Tanja OstojicBesides the exhibition’s underlying argument that art has a gender, it soon turns out that it also has a geography. Reading the works presented without referencing the fact can lead to serious misinterpretations. As Izabela Kowalczyk writes, “The different trajectories of women’s life in the West and here, in the Eastern bloc, are not without significance. When women in Central and Eastern Europe were almost forced to work, their Western peers fought for their right to pursue professional careers, when here, in some countries at least, abortion was treated as a contraceptive, women in the West fought for their right to it.” The political difference meant that Eastern European women artists’ practices often lagged behind and diverged from those of their Western colleagues. An evident eroticisation of the woman’s image was a protest against the notion of the body as neutral and genderless. Women artists found it hard to criticise the regime of perfect looks because it was associated chiefly with the allure of consumer-culture luxury, access to which remained highly limited. Being beautiful in Natalia LL’s Consumer Art (1972) involves being aware of one’s own sexuality and controlling the other’s gaze, controlling one’s own pleasure. The multiplied images showing a smiling model sliding bananas and sausages into her mouth can cause a sense of discomfort. The model performs an act of symbolic sexual consumption, evoking oral sex but also castration. She plays with licking and spitting out food and with the viewer’s fascination. It is her who controls the situation, challenging the traditional system of power in the context of gender: watching, choosing, disciplining, directing, filming.

Checking

Eva Filova, No differance, Slovakia 2001

Eva Filova, No differance, Slovakia 2001

courtesy of the artist, photo: Tomáš BlonskiThe poster for Gender Check is a reproduction of Vlado Martek’s work that shows a red sickle dressed in a pair of black panties with the word “Neću” (Croatian for “I don’t want it!”). The slogan demands freedom in defining your identity, in individually deciding who you are and expressing yourself in many ways that don’t have to be consistent with the traditional notions of masculinity or femininity; opposing whatever established patterns may exist in this regard.

In the show’s third part, Postcommunist Genderscapes, the body becomes fluid, revealing the conventions of game-play and masquerade. This part is informed by the theories of Judith Butler, opposing gender identity as a performative subversion established by repeating certain actions and gestures, forms of behaviour associated with gender. The Cartesian cogito is replaced here by a dynamic construct whose meaning can be searched for only on the path of constant confrontation. Put up for sale, it changes according to the customer’s needs. Nothing is as real as it seems.

Vlado Martek, Neću / I don't want it,

Vlado Martek, Neću / I don't want it,

Croatia 1979, Zattoni, photo: Vlado MartekKristina Nagy moulds the shape of her breasts, firm in one picture, slack in another. Her body changes as if it were made of plasticine. In Looking for a Husband with an EU Passport, a series of posters and leaflets, Tanja Ostojić, instead of using an image that would emphasise her physical attractiveness, used one of her skinny, shaved body, declaring conformity with a predefined model. The artists perform a transgression, reversing the male notion of female sexuality and making visible in the field of art something that long remained outside it. Thus the pornographic context of many of the works presented here appears subversive. Among the works challenging the division between the artistic and the obscene is Katarzyna Kozyra’s video In Art Dreams Come True where the artist, assuming various roles and camouflaging her sexuality, does a striptease in a gay club, revealing male genitals which she then removes. Completing the show’s most disturbing part is Alicja Żebrowska’s video The Mystery Is Looking, installed at the end of a long grey tunnel. A glass ball has been placed inside a vagina. Instead of an arousing fragmentation of the body prepared for an observer, what we get is a situation, disgusting in its bizarreness, where the eye changes its position. It prevents access inside the body, catching the embarrassed viewer in the act of obsessively peeping and looking. A close-up of the crotch proves hard to bear this time. Nothing obstructs the view. Juxtaposed with the glass eye, the exciting folds of skin, the site of ecstasy, are no longer anonymous. The frightening meat-like form fills you with a sense of disgust.

Answer!

Katarzyna Kozyra, Tribute to Gloria Viagra.

Katarzyna Kozyra, Tribute to Gloria Viagra.

Birthday party, Poland 2005, the recording

of a squoted event, still, deposit of Zachęta

National Gallery, photo: Katarzyna KozyraAmong the impossible throng of the works, unfamiliar names, the multitude of media used, most of the pieces are actually quite unassuming. Demanding concentration and careful isolation from the dense pulp of bodies is, for instance, Ras Todosijević’s video Was ist Kunst, Marinela Kozelj? The Serbian artist repeated in 1976 a series of performances in which he kept asking a female model the same title question. Watching their documentation, the viewer has a sense of tension that accompanies this weird account of something that resembles a brutal interrogation. We assume the role of a voyeur watching a perverse argument. The question “What is art?” suddenly appears very personal, inappropriate, cruel. It’s hurled like an insult. A male hand touches a female face, kneading it like dough, soiling, yanking like a doll. Her head jerks and returns to natural position. The neurotic question, asked in an ever louder voice, evokes no answer. The woman is passive, letting him jerk her around. In fact, why doesn’t Marinela Kozelj say anything, simply to protect herself? She seems unmoved, emotionless, but also self-confident. Kozelj makes the decision not to give an answer. She won’t be forced to give one. Her lack of reply undermines the cliché of active man artist vs. passive muse/model.

Rovena Agolli, In any of my dreams,

Rovena Agolli, In any of my dreams,

it's never the way it seems, Albania 2002

courtesy of the artist, photo: Rovena AgolliGender Check is neither an aggressive classification attempt nor a chronologically arranged collection of works about gender. It reveals important absences and concealments in Central and Eastern European art history. It brings together accounts of identity self-descriptions undertaken by successive generations of artists, documenting attempts to express oneself in the most immediately available medium, one’s own body. Testing its limits and defining its position often involves stigmatising and mutilating, becoming a guarantor of the order so created, which you enter only at a price, often a high one. And yet, in this confusing of the complacent viewers, the exhibition doesn’t force them to respond to the command given by its title. The interrogations are over.

Gender Check. Feminity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe. Curator Bojana Pejić. Zachęta National Gallery of Art, 20 March – 13 June 2010

translated by Marcin Wawrzyńczak