The characters in Peter Weir’s new movie, which opened the 4th edition of the Off Camera festival, travel from Siberia, through Mongolia, the Gobi Desert, the Himalaya, and all the way up to India. Based on real people from Stanisław Rawicz’s The Long Walk, the characters are a perfect embodiment of independence, which happens to be the festival’s motto. “No more lies,” says the American, played by Ed Harris. Characters played by Colin Farrell (Valka) and Jim Sturgess (Janusz) stood up to Stalin’s regime and paid a very high price for their actions. Not to trivialise their sacrifices, but the work of an independent filmmaker preparing his debut is very similar to a terribly exhausting, long march. The entire crew, the director, the producer, they all undertake a shared risk, and place all their eggs in one basket. The place of Peter Weir, the festival’s main guest, in the history of moviemaking is secure and undeniable. Weir, however, got very emotional when he recalled his first steps in the movie industry during an interview with Elvis Mitchell (himself a member of the International Dramatic Competition jury) “I nearly died after finishing my debut, I was so exhausted. How do the others make it?” The applause with which Weir was greeted by the attendees leaves no doubt that his work was not for naught.

Peter Weir on the set of The Way Back, photo OCP

Peter Weir on the set of The Way Back, photo OCP

The festival, which ran from 8 to 17 April, was also a long walk, a walk through Korean, Irish, and German cinema. The “Discoveries”, “Sundance Institute Series”, and “Making Up For Lost Time” sections created a safe haven for all other intriguing phenomena that have made their mark on cinematography during the last few years. Every movie is a sort of travelogue. Just looking at the movies screened during the festival, we can easily see the wide concept of “journey” being run through all possible variations of “rite of passage”. Michał, played by Tomasz Kot in Erratum, visits his hometown and gets all tangled up in his past. The characters in Notre jour viendra try to escape from a reality that discriminates against gingers. The winner of the International Dramatic Competition, Musan il-gy, is a story of Korean émigré’s struggle to find employment in a foreign country, while the American picture, Wolf Knife is a story of two teenagers embarking on a trip to find the biological father of the more domineering girl of the pair.

The Master’s Path

“The Master Class” section of the festival, whose first guest was Peter Weir, was also a sort of a travelogue. The Australian director was awarded the Commandery of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland for his work on The Way Back. It gave the opening ceremony a very solemn air. The next day, the director of Picnic at Hanging Rock was more relaxed, telling funny stories about his early work. He recalled meeting Alfred Hitchcock, the master of suspense, which in Weir’s work takes on almost a metaphysical, irrational character. The young auteur, standing face to face with the creator of Psycho, was trying to explain paraphrasing his famous “shower scene” but in a bloodless context. Hitchcock’s answer was: “It’s okay.” Well, some movies just work better without murder in them. When asked about which of his movies he likes best, Weir answered that the ones he loves most are the ones that haven’t found an audience, adding that he’d like to re-edit The Last Wave, as he’s not satisfied with the current ending. He said it just wasn’t possible to fit a realistic depiction of the apocalypse in the film’s tight budget.

Jerzy Skolimowski, Master Class, photo OCP

Jerzy Skolimowski, Master Class, photo OCP

Jerzy Skolimowski attended the festival as a jury member and painter. During “Master Class”, he mostly talked about his adventures in directing film, succinctly but exhaustively answering Mitchell’s questions. When asked about Ręce do góry and the four-eyed Stalin affair, he vowed never to return to political cinema. Regarding Knife in the Water, Skolimowski claimed that the story was written by Polański, and his own contribution was suggesting that Polański limit the story’s timeframe and set it on a sailboat. In interviews, Skolimowski introduces himself as a painter who only occasionally makes movies. When asked about his paintings, exhibited in the Wyspiański Pavilion during the festival, Skolimowski’s answers were full of passion. When painting, you’re making all the decisions regarding the canvas. “Painting is like zen meditation,” he told his interviewer. “How can you describe working on a movie set, then?” “A bordello would be a good analogy,” Skolimowski answered, eliciting a big laugh from Mitchell.

By hook or by crook

Whatever the difficulties during the production phase, the results presented at the festival were very satisfactory. “The Far East” section was especially strong this year. The previous edition of Off Camera included a review entitled “The 15th Anniversary of the Pusan Festival”. This year, six South Korean films were screened during the festival (plus Musan il-gy screened as part of the Dramatic Competition), all of them showcasing the diversity of South Korean cinema.

Poetry, dir. Lee Chang-dong, South Korea 2010

Poetry, dir. Lee Chang-dong, South Korea 2010

The best example of Asian poetics subjugating the viewer, and not the other way around, is the picture directed by Lee Chang-dong, which was awarded the Palme d’Or in Cannes for best screenplay. Poetry is a story about an older woman (Mi-Ja) raising her grandson on her own. He is a troublesome kid, and is one of the suspects in a gang rape of a schoolgirl that later committed suicide. To smooth over the situation, the parents of the assailants are planning to raise a large sum of money as compensation for the girl’s mother. In the background, the director weaves a seemingly banal story about a poetry course taken by Mi-Ja. The dilemmas that the older lady faces make it hard for her to write poetry. Chang-dong created a beautiful, yet sad story in his film. He doesn’t end it with a warning, but he shows us a picture of a raging river. Mi-Ja’s life is getting increasingly complicated. When her memory starts to fail, the doctors diagnose her with early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. But despite her ailment, she is the only one in her course to present her poem before the teacher.

Musan il-gy, dir. Park Jung-Bum, South Korea 2010

Musan il-gy, dir. Park Jung-Bum, South Korea 2010

The winner of the International Dramatic Competition, a picture by Park Jung-Bum, also premiered at the Pusan Festival. The movie’s main character, Jeon, is an introvert. As a South Korean émigré, his employment prospects are rather slim. He also lacks the confidence necessary to get a girl from Sunday school interested in him. But he is a very conscientious worker, who doesn’t shy away from menial jobs, like sticking up posters or cleaning up the karaoke bar. The “poetry” in Park Jung-Bum is very discreet, hidden behind his neorealist style, an occasional gag, and the ubiquitous feeling of injustice. Like in Re-encounter, the protagonist’s situation and emotions are best reflected by the dog. A stray, exposed to fate’s cruel hand – just like Jeon, forever destined to being an outsider.

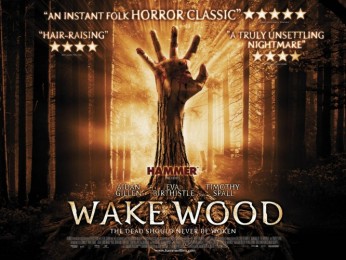

Films screened during the “New Irish Cinema” section also make use of mood. But they tend to depict more extreme emotional states. In their case, the journey is expressed through: a psychological transformation of the protagonist (Muldowney’s Savage), confronting the trauma of losing a daughter (Keating’s Wake Wood) and the maturing of three brothers during their hunt for a gift for their father (Frazer’s My Brothers). But the way the directors build tension is the most intriguing thing about these pictures.

Wake Wood, dir. David Keating, Ireland 2011

Wake Wood, dir. David Keating, Ireland 2011

Wake Wood is promoted as a descendant of Hammer Horror, although the storytelling tools it employs are typical for Hollywood productions of the last decade (Saw, Hostel, The Hills Have Eyes). The tension quickly yields to massacre. Savage meticulously describes the transformation of an assault victim: from a quiet paparazzi (although one fascinated with tragedy) to a street warrior, visiting vengeance on bandits and their cohorts. His fear of leaving the house evaporates. Anabolic steroids and a hunting knife kept always within arm’s reach are Paul’s new masters.

Conor Horgan’s One Hundred Mornings, on the other hand, is completely different. Built on a premise similar to Hanneke’s Time of the Wolf and Kramer’s On the Beach, Horgan’s movie tells a story of the end of civilisation using subtle psychodrama. Four people are hiding out in a cabin with no running water or electricity, living off scarce reserves of food. The situation outside shows no signs of improvement and the local law enforcement officers control the countryside like villains straight out of Mad Max. Horgan uses the moment of “violation” with great care, leaving the true terror intangible. He claims that the most terrifying thing is the awareness of limitations of a given situation – the possible scenarios, or their lack, for the characters still alive.

On the sidelines

The journey of Weir’s characters didn’t consist of marching alone. There were days of rest, days of looking for supplies and fighting against the will to give up. But there were also moments of comfort. The oasis seen while walking through the desert didn’t turn out to be a mirage, and a Mongolian offered the characters his own supply of water when they were trudging through the endless steppe. These movies that stray from the beaten path and escape expectations seem to us almost as coming from another world.

Carancho, dir. Pablo Trapero, Argentina 2010

Carancho, dir. Pablo Trapero, Argentina 2010

Carancho, screened in the “Discoveries” section, has elements of Borgesian prose, which subjects the world and the characters that inhabit it, to universal rules. The theme of Pablo Trapero’s movie is car crashes and collisions. Sosa is a legal advisor representing the injured, who is sometimes forced to arrange crashes for the sake of his clients. He knows the EMTs and the doctors on a first name basis. Luján is a young EMT, a first responder for Sosa’s future clients. Trapero’s movie uses genre tropes as one might use a gearshift – a socially involved film turns into a love story and later into a gangster flick. When the movie gets into high gear, the directors deftly uses a tracking shot in the finale to take us back to square one. To a car crash.

Saverio Constanzo’s picture overwhelms the viewer in a similar way. In The Solitude of Prime Numbers he shows us the story of Alice and Mattii, checking in with them at different points in their lives: when they’re 17 and 19, and later 41 and 43. These eponymous prime numbers, because of their solitary mathematical nature, are supposed to reflect the characters’ alienation. Just like in Saura’s Cria Cuervos, the feelings of alienation are a natural, inseparable part of childhood. It’s an “unknown land”, where there also is cruelty and loss. Constanzo’s movie also has a patron in Dario Argento from his “Suspiria” period. The film’s soundtrack surely inspired Mike Patton, who worked on the soundtrack for The Solitude of Prime Numbers. But in Argento’s movies, trauma served only as a psychoanalytical backdrop that explained the murderer’s actions. Constanzo does not try to explain anything; in his movies, the wounding becomes the horror.

Never mind the circumstances

The “independence” mentioned in the festival’s subtitle is a very ambiguous term. Almost every director has given a different answer when asked about it. Some claimed it’s the freedom to choose the subjects of their movies, others mentioned fighting against totalitarian systems and conditions of the market. Perhaps the most practical is the explanation that Janusz, played by Jim Sturgess, gives his companions. His perseverance reminds them to never succumb to circumstances.

translated by Arthur Barys