At the heart of Marek Lechki’s pure, idealist film lies a paradox. The subject of Erratum is a reconstruction of the story of a certain homeless man. This task is selflessly undertaken by a person who lacks a sense of identity, an identity which he rebuilds by delving into the life of another. His efforts are handsomely rewarded. After his own death, the homeless Antoni helps organise and improve the life of the upright citizen Michał. Thus sympathy offered to someone’s anonymous existence imperceptibly returns to the donor. As it turns out, there is more than one measure of homelessness.

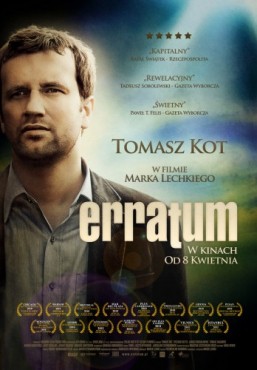

Erratum, dir. Marek Lechki,

Erratum, dir. Marek Lechki,

Poland 2010, in cinemas from 8 April 2011The filming technique and composition in Erratum strike us right off the bat. The close-up makes nothing closer, and actually creates a greater distance between the audience and the photographed object. The nature of the object escapes its very name. They’re often mere particles, fractions instead of wholes. We are drawn in to a part of someone’s face, to the line of the chin, the eyes and the gaze cast off to the side, to the hands clasped above the head, to the head itself, tightly squeezed into the left corner of the frame, as if embarrassed by its own presence. Przemysław Kamiński’s camera also seems troubled by its mission. It spies on the father with a tentative, son-like look; it glimpses the profile of a motionless, silent person from behind the chair, going no further without permission. The delicateness of the imagery is charming, but it also has an increasingly alarming false bottom. The fragmented image turns out to be a figure of an atomised world.

We can suppose the cutting of the character’s umbilical chord is what’s behind it. The ties to the mother have been broken by centrifugal force, now masked only by tradition. The myth of the safe, motherly refuge becomes a thing of the past. A rural cottage placed somewhere on the outskirts of the city becomes dilapidated and run down, overgrown with lichen and moss; abandoned by Walczak – a future homeless man – it becomes a haven for other homeless people. Erratum tears down the myth of the place, especially given that the nearby Bogusz family apartment bears few signs of family happiness, much less the promises of youth. Most young people abandon this place and head to Warsaw. Their new social circles change them. But do they leave them uprooted and resembling the main character in Erratum? The creators of the film might have something to say about it: Lechki (originally from Wołów), Kotys (born in the countryside outside of Kielce), Kot (a citizen of Legnica, long since steeped in metropolitan sweetness). Each of them has their own experiences. As does the theatre guru Krzysztof Warlikowski, from the Szczecin neighborhood of Golęcin, a possible inspiration for Michał: he has only visited his hometown a few times since he left, and – as he admits – he can barely get himself to say the name of the blue-collar borough of his youth.

Erratum avoids a more general analysis of this phenomenon. Broken ties between people and places are discussed in psychological, not social, categories. But this does not always prove sufficient, despite Marek Lechki’s exceptionally sensitive observation skills. The screenplay doesn’t do justice to the excellent directing and outstanding acting (from Kot and Kotys’ excellent performances to the colourful characters of Michałowski, Rogalski, and Pomykała, and the supporting roles played by amateur actors). Erratum owes its artistic merit more to its elements than to the way in which it addresses the issues. An encounter between Michał and his childhood friend, reminiscent of so many confrontations of this type – Le Beau Serge, Intimate Lighting, The Structure of Crystal – fails to produce the same consequences. It opens nothing, nor does it entangle the plot. The fire consuming the friends’ tower of memories before their very eyes is little more than decoration. Both seniors, Bogusz and Walczak, die while still alive – seemingly from loneliness, but how could one be lonely in such a neighborly community (Nawrocki)? Their sons share a similar grudge against their elders. Could this dual coincidence merely serve to provide symmetry? In the role of his life, Tomasz Kot is given the non-trivial task of making his character believable. Michał, as a respectable citizen and affectionate master of a stray dog, makes no effort to hide his withdrawn, grumpy demeanor from the very start. But why? It’s hard to grasp the troubles of a bored office worker when he’s a happy husband and father. One thing that comes to mind is the ironic detachment that the director has employed elsewhere. “You’re a weird person”, says to Kot Janusz Michałowski, who plays an eccentric and thoroughly humanised police commissioner, completely dissimilar to Porfiry Petrovitch.

Erratum’s director has managed to touch upon another important issue, that of deteriorating communication between fellow men. The signs are prosaic, or at least far from the existential stuffiness of Bergman. Lechki approaches with all seriousness that which in any other context would be considered an expression of male strutting. He has waded deep into a world where characters from beer commercials, like Indians in children’s books, swap monosyllables around a campfire, where Polish youth plow through life with one four-letter word on their minds, and where fathers confuse their homes for barracks. The conversational model “What’s up?” / “Nothing much.” makes several appearances throughout Lechki’s film. The polite yet neutral sentences gleaned from English and French phrase-books would rival these dialogs – even the clichéd Russian response vsyo normalno would be superior – at least it doesn’t stall the conversation. Zbyszek is well aware of this artificiality when he informs a friend that he’s had a baby, tossing in the completely out of place “for example”. He succeeds in getting Michał to open up to him when the character comes knocking at his door one night, heavy with the burden of his unnamed emotions. Who knows – perhaps Michał takes after his father in his silence, and maybe he will helplessly seek refuge in someone else’s conventional writing in the future. There are greeting cards for people like him, published in mass quantities and ready for every occasion, prostheses for natural feelings. “Say hi to Krzyś” (his only son), spoken in similar greeting card fashion, does not bode well.

This linguistic black wall is not a question of a poor vocabulary. Erratum is like a call, a knock, asking for a chance to talk. The son asks for nothing more of his father – nor does Zbyszek demand anything more from Michał. It would seem that the character’s wife expects little else from him. The son expects some fatherly gesture, something more than an off-hand “How was school?” and a souvenir from his latest trip. If even as good a man as Michał can’t bring himself to give it, what can we expect of others. What’s missing is more than just words – it’s body language. After all, lovers can talk without words. There’s really not much to it. At the most important moment in their lives, the son and father learn to use Morse code. The wall, like that of a prison cell, becomes a good conductor of warmth.

Lechki creatively explores an area of emotion not commonly (and not willingly) visited in Polish cinema. Suffice it to mention the awkwardness evoked by Stanisław Różewicz’s work, or the equally noble yet singular films of Dorota Kędzierzawska, or the recent surprise at Andrzej Barański’s decision to dramatize A Few People, a Little Time. The path seems to have been blazed in recent years, thanks to such artists as the acclaimed director Andrzej Jakimowski and the yet-undiscovered Michał Rosa. Lechki’s film has a peer in its audience, who watched Erratum with full attention, doing justice to the director’s intentions. As a demanding storyteller spinning a subtle yarn, Lechki avoids preachiness.

The entire film can be reduced to a few basic rules well known since the times of Mikołaj Rej, as well as a couple of rather useful bits of advice. Remember that there are good things that seem bad. Honor thy father, as thou art hardly better than him. Thou shalt not have other bosses before your loving and beloved family. Watch over thy friends. Less speed, more haste: you never know what awaits you around the bend. Take that damned cell phone out of your ear, unplug your battered brain. And, perhaps most important: when blinded by oncoming cars at night, squint. Only then will you see the person on the shoulder of the road.

translated by Arthur Barys