PAWEŁ SITKIEWICZ: How did your childhood interest in animation, in films, and in comics influence your later creative work?

PIOTR DUMAŁA: I’m someone who lets various sources of inspiration work through me, and I rework them in my own way. I’m fascinated by a variety of things and they ripen into something that you can call creative work. I think that’s the main reason I did adaptations of Dostoyevsky and Kafka. I saw a tremendous potential in their books, something I could turn into an animated film. On the other hand, though, I’ve written my own screenplays that came from dreams, memories, observation, stories I’d heard, or something like revelations. Yet, I gained popularity through adaptations. Even Czarny Kapturek (Little Black Riding Hood) was a parody of a well-known folk-tale. For certain, when I watched films as a child and fell in love with that world on the other side of the screen, I saw my future there – like in a magic ball.

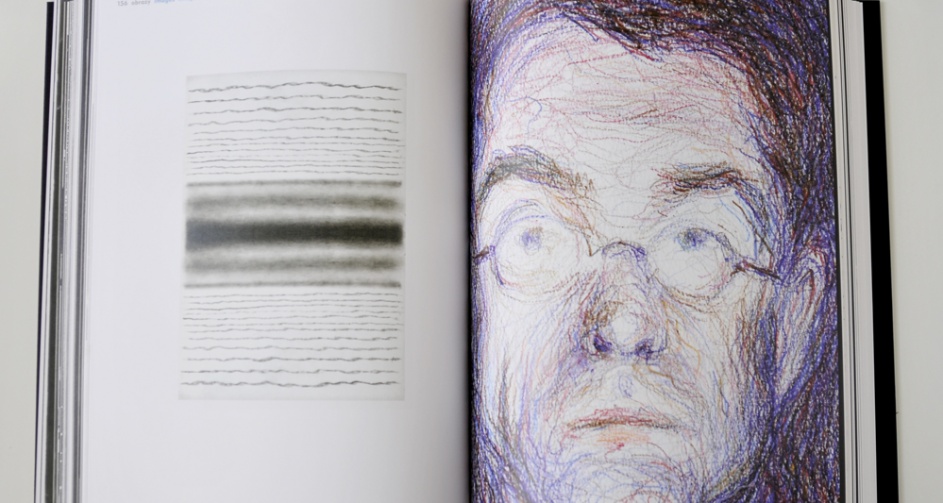

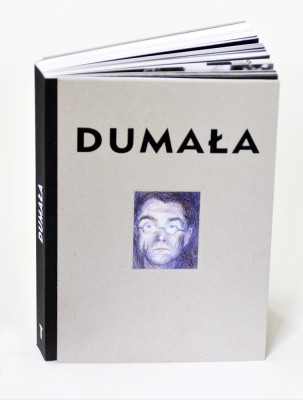

DUMAŁA – the book

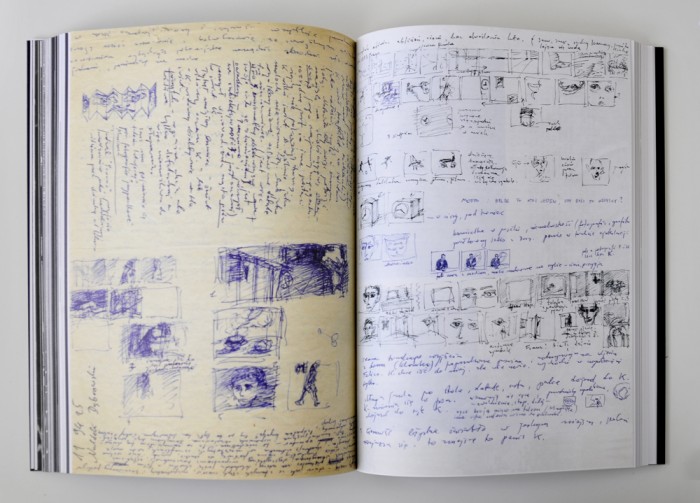

Dumała is a book published by Słowo/Obraz Terytoria in Polish, English and Spanish. Piotr Dumała is one of the most interesting Polish film makers. He is a director, animator, illustrator, writer and a critic. The book is a journey into Dumała’s imagination and memories, rich in both graphic materials such as sketches and family photos, and in text – his literary forms and letters.

This talk is an excerpt from the book.

What are your first memories of the cinema?

It was what they called morning shows for children. They showed several short films together. I remember, one time we went with our parents on Sunday to the cinema, and afterwards a lively discussion of the movie took place. It was a story about some chickens who were going to a party and were trying on hats and fancy clothes in front of some mirrors. We were all very impressed. It was like we’d seen the world in a crooked mirror. I remember my mother was really very taken by the movie. Back home there was more talk, and a neighbour came over and we told her about these chickens. Maybe the fact that my parents got so worked up about the film also influenced my decisions in the future. I started to dream of making animated films very early in my life. (...)

Did you try to get your feelings about films you’d seen down on paper?

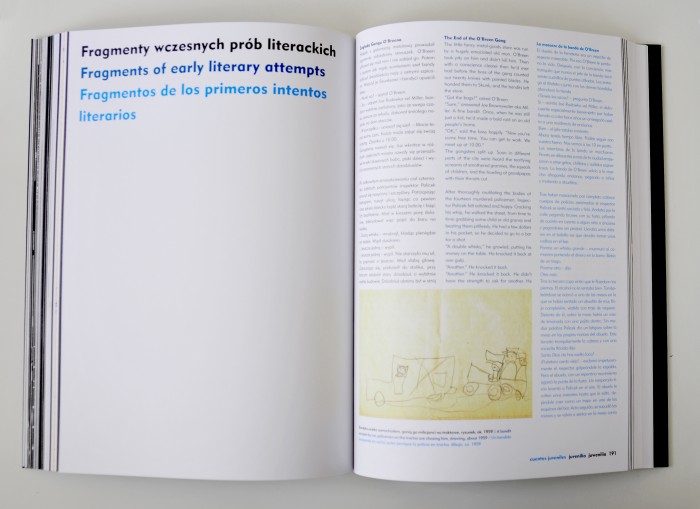

Maybe unconsciously… I drew primitive comics and I wrote – first of all, gangster adventure stories, and then stories that were decidedly macabre. In those juvenile pieces of work, everyone killed everyone else – horribly and without pity. Gangsters slayed children in the streets, and if they twitched they finished them off. A vampire bit old ladies to death. This had a parallel humorous dimension. I made fun of madmen and priests, figures who were real and invented. Sometimes I got funny names for them from obituaries. It was at that time I made up a grandfather figure who became my ideal. He was modeled on my grandfather. I gave him the qualities of a superman – he knew karate really well, he was bold, clever, intelligent. At the same time, he looked like an innocent old man with no teeth, someone who barely moved at all, lived off buns soaked in milk, and spoke in a tiny high voice. Everybody thought he was some kind of feeble nobody, and then they ran into his monstrous power. (...)

Dumała, Słowo/Obraz Terytoria, Gdańsk 2012You started to write your own stories very early on. What were your literary inspirations?

Dumała, Słowo/Obraz Terytoria, Gdańsk 2012You started to write your own stories very early on. What were your literary inspirations?

That was a strange business, because I didn’t read a lot of books that were hits then. When I was a child, I’d never heard of the Moomins or Winnie-the-Pooh. Out of the heroes of children’s literature, I knew Koziołek Matołek (Matołek the Goat) and the Dragon from Porwanie Baltazara Gąbki (The Kidnapping of Baltazar Gąbka). Later I fell in love with the adventures of Tomek Wilmowski with Józef Mark’s illustrations. I adored Bohdan Butenko’s illustrations too. Those definitely influenced me to want to make animated films. They were like films. They gave the impression they were copies of the action and that they were running parallel to the book’s content. I remember the illustrations to Woroszylski’s Cyryl, gdzie jesteś (Cyril, Where Are You?) and Domagalik’s Pięć przygód detektywa Konopki (Detective Konopka’s Five Adventures). And long before that the picture story Pan Motorek i Panna Kreseczka (Mr. Motor and Miss Line) that came out in the magazine Płomyczek at the end of the 1950s.

When did you come across Dostoyevsky and Kafka for the first time?

Much later in high school. First I read Crime and Punishment and The Idiot, and then all of Dostoyevsky’s books. Earlier at the end of junior high, I got this real mania for Thomas Mann. I read everything. He was the first writer I loved. Dostoyevsky took over from him, and then there was Kafka. After them I don’t think there were any others. But Chekhov, Gide, Hamsun, Camus, Hašek were important for me. But by degrees literature stopped being important for me like it was when it helped me make my own choices and define who I am.

You’re labeled as being an artist who makes psychological and poetic films. But your films from the 1980s – like Lykantropia (Lycanthropy), Czarny Kapturek, and Nerwowe życie kosmosu (The Nervous Life of the Cosmos) – go against that completely. You’re a humourist, although your sense of humour can be brutal. And you certainly don’t hide your fascination with the burlesque and with comic strips. Why have you got this reputation?

I swear I’m doing everything to be a humourist again. Because it’s great fun when you’re making the movie, and there’s no pleasure like it when people in the cinema burst out laughing. Apparently, after Latające włosy (Flying Hair) the viewers were amazed that the guy who made Kapturek made poetic movies… My ideal movie is one that moves between humour and horror. And best of all, if those two extremes make a circle and come together. For a long time the model of perfection for me was Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby, something like a mystical horror movie that is complemented by comic counterpoint.

Dumała, Słowo/Obraz Terytoria, Gdańsk 2012

Dumała, Słowo/Obraz Terytoria, Gdańsk 2012

Czarny kapturek also moves between horror and humour. For the 1980s, that wasn’t usual in Polish animation. What was the reception like?

I remember that Czarny kapturek was shown at the Konfrontacje festival, paired with a non-animated film, some Hungarian one, I think. Because it had won a prize in Varna, it could count on better distribution (shown in cinemas as a second-feature, as a film that had won a prize at festivals). I overheard the conversation of some students from the Academy of Fine Arts who said: “Did you see that amazing second-feature?” It turned out that for young people it was pretty much the hit of the Konfrontacje festival that year. And it’s still funny today and people write about it passionately on internet forums. For some, though, it’s still a vulgar movie, which is hard to believe today. Its success in 1983 was probably because there was no tradition of films like that in Poland. Olo Sroczyński and Julian Antonisz made humorous movies. But they were quite different. Antonisz was interested in social satire, and Olo had his own hermetic obscene world. Czarny Kapturek was based on a well-known folk tale and had classic burlesque in it, and mixed that up with the macabre.

Do you acknowledge any masters in the animated cinema? You’ve written several times about your colleagues Berthold Bartosch, the Quay brothers and Yuri Norstein.

That changes all the time. There was a time when I’d mention Norstein and the brothers Quay in the same breath. But now? Norstein’s gone silent, and the Quays make quite different films nowadays. I still get blown away by their Street of Crocodiles, but those movies have dated a bit. Now I’m looking for something different in the cinema. I’m going back to my first loves, like the silent cinema or burlesque. Probably it’s because I’ve started to make films with actors. I need the physicality of actors, the physicality of a world that’s both real and not, at the same time. Animation we know isn’t real. From the first moment we see everything is in quotation marks.

Dumała, Słowo/Obraz Terytoria, Gdańsk 2012

Dumała, Słowo/Obraz Terytoria, Gdańsk 2012

Did those former masters teach you anything? What’s left from those old enthusiasms?

I think it was because of Norstein that I made the film about Kafka. I was at one of his lectures in Warsaw, around 1988. He was making his The Overcoat then, based on the Gogol story. He showed bits of it and spoke about it. I’d finished Wolność nogi (Freedom of the Leg) and I thought I’d said everything there was to say in animation. Thanks to Norstein I saw that animation can have something magnetic in it; it can create an alternative world that will seem real, physical. In Norstein’s work everything was real: the air, the light, the shadow. I believed in that third dimension. I think that’s when I had a vision to deepen animation and to make an animated paradocumentary about Kafka. And the Brothers Quay? They didn’t have any direct influence on me. I was happy that there were guys like that. We became sort of friends. They were my spiritual brothers.

What’s the connection between literature and cinema in your films?

Once in the past I was hugely attached to stories; I wrote through film. Also that’s what you learn at Polish film schools. I think most directors make this mistake, because that’s what audiences want – they want to be told a nice little story, literature. At the same time when I go back to films that have stuck in my mind, I don’t recall their content. I remember individual scenes, isolated moments, facial expressions, gestures, tension in one of the scenes – so, I remember images. The cinema uses non-verbal images; more and more I understand the truth of those words. I know that when I stop making films that tell a story, I’ll lose lots of viewers who used to like my work. My former Polish teacher told me: “You write through film.” And that’s the way it was then. Lykantropia, Latające włosy, and even Czarny Kapturek – those were a little bit of my writing, blown up to A1 format. Now I’m sure I don’t want to write through film. I’m running away from literariness. The literary level is a pretext and a structure, the dialogue is sound effect. I’m looking for the cinema’s real language – both in animation and in film with actors. It’s the image and its editing that has to tell the story. (...)