Alan Lockwood talks to Rita Gombrowicz

ALAN LOCKWOOD: You worked in the early 1970s with Maria Paczowska, to have a version in French of the hundred pages that Gombrowicz left in his Kronos folder. How did you use the information it revealed for your research into his life?

RITA GOMBROWICZ: Maria was the first person I showed it to, the first who saw the complete Kronos in Polish. Because she and her husband, Bohdan, were our close friends. She knew everything, she became the representative of Witold to tell me what Kronos said. This story is very special. She translated orally into her French, and I noted everything and I typed.

At this time, when you had the translation with Paczowska, were you planning to go to Argentina?

RITA GOMBROWICZ

Gombrowicz’s late life’s companion and wife. Curator of his work, author of Gombrowicz in Argentina (1984) and Gombrowicz in Europe (1988). Author of foreword and co-author of footnotes in Kronos.

This is very interesting. My intention had been to go to Argentina with Witold. After his death, in 1969, I wanted to go, but when I read Kronos, I decided to go there to complete its information. For me it was a pleasure, a duty, everything.

A necessity.

Yes. Witold was thinking all the time about Argentina. He received a lot of letters from Mariano Betelú, from Juan Carlos Gómez. It was natural to go there. I made a list of questions from Kronos of what I wanted to know about his life in Argentina. And never took the manuscript with me, even a photocopy, nothing. Just the list of questions, like for precise details about Tandil, for example. Who was the owner of the house he stayed in there, who was this person? So I met with Mariano Betelú, with Dipi (Jorge Di Paola – A.L.), with everybody.

Yet only Maria and I knew that Kronos existed. I am surprised to this day. When Alejandro Rússovich (who translated The Marriage into Spanish – A.L.) came to my home in Milan in 1976, he did not know. He told me he was very surprised, that it was impossible. We worked together from a photocopy inside my home, he only saw the Argentina part, and he explained everything about those years. But that was from the French transcription.

In your introduction to the new edition, you write that Gombrowicz told you if a fire happens, take Kronos, his contracts and run.

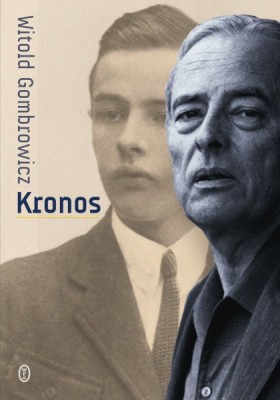

Kronos

With the publication of Kronos on the 23rd of May by Wydawnictwo Literackie, Witold Gombrowicz’s handwritten last work arrives, decades after his death in 1969. A staccato monthly accounting kept as he wrote his famous Diary, Kronos is the final unmasking by the infectious master of that form. WL’s premiere edition includes facsimiles, photos, essays by Rita Gombrowicz and Jerzy Jarzębski, and extensive footnotes by them and Klementyna Suchanow. They spoke with Biweekly about Kronos, its secretive past and the validity of its publication today.

I think it had been the first time he told somebody about it. The only person who read Kronos in Polish other than Maria was Gustaw Kotkowski (Gombrowicz’s cousin and confidant – A.L.), also in my house in Milan, who told me he did not know. Gustaw was, if it’s possible, more discreet than Witold. It’s very special, you know. It’s a miracle, to keep silence, above all for me, because I speak! But Kronos was absolutely sacred.

You had this unique document and you practiced discretion. But why?

How to explain? If I began to say something about it, I would have to explain it all. It was instinctive. But when I published my first book Gombrowicz en Argentine (1984), I published small extracts near the end. It was for Polish readers, to say it exists. But no one asked me anything about this, ever.

With the sale of the Gombrowicz archive to Yale University in 1989, you separated Kronos from the archive.

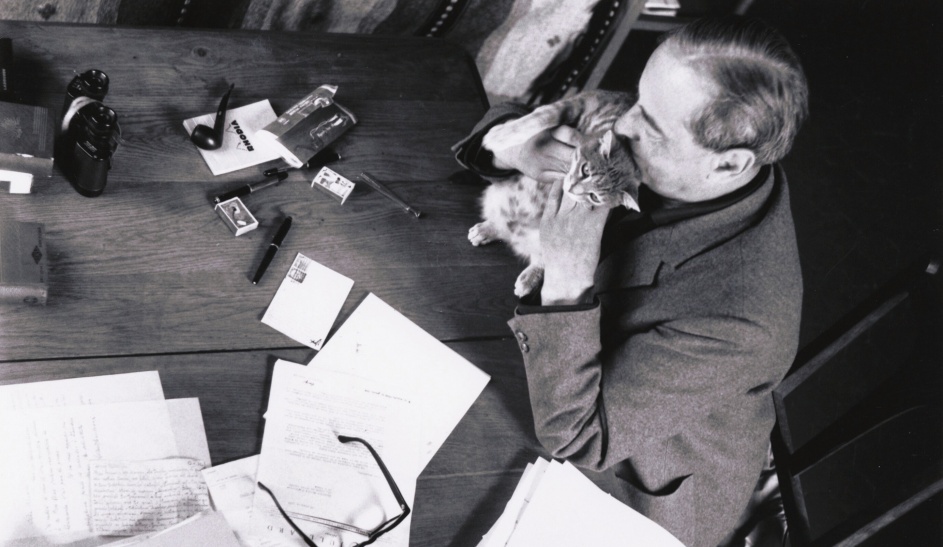

Witold Gombrowicz, Kronos.

Witold Gombrowicz, Kronos.

Wydawnictwo Literackie, Kraków,

460 pages, in Polish bookstores as of May 2013Yes. I was not ready to give Witold up, and decided what to do with Kronos with Ann Heilbronn from Sotheby’s, the head of books and manuscripts, who helped me for six months to prepare the archives for Yale. We decided to wait with Kronos. I thought maybe it was better just to put the manuscript somewhere in a library, for professional research. After this, I thought to publish, except the Vence years. But only Argentina, without Europe? It’s not the truth. And now I am, as Witold said, a pure spirit. When we become old, we don’t have the same ambition about private things.

Now, for the physical manuscript, the publisher, Vera Michalska, is the owner, and she will deposit the manuscript, because I wanted to give it as a gift to Poland. Vera took the decision for the National Library in Warsaw, as the best place for the conservation of manuscripts. The Kronos manuscript is old, it is now time to preserve it.

What about publication of Kronos in the next languages after Polish?

I feel we have to use this material, but the presentation can be different. Maybe we can use more manuscript facsimiles, it depends. But the text and the footnotes, yes because we worked a lot, as you know.

Regarding the years after Witold’s return to Europe and Vence, what did you feel was important to add for readers to know, along with the text?

Because I am so inside of this, I can’t imagine what is really important to know. Maybe it will depend on the reaction of Polish readers. Today I met a journalist from Gazeta Wyborcza (Polish daily – ed.), and told her that Kronos is to clarify the situation. And she answered “Now, for me, it is more mysterious! I want to know why Witold wrote this, and why he wanted to remember.” For the future, this is good we have a lot of questions!

Alan Lockwood talks to Jerzy Jarzębski, Klementyna Suchanow

ALAN LOCKWOOD: What’s your assessment of Kronos, now that it is available at last?

JERZY JARZĘBSKI: Well, now it begins, in fact, with the reception of the book, and with the reception of our work. It’s very interesting for people who deal with Gombrowicz. For other people, we can’t know yet.

KLEMENTYNA SUCHANOW: Like the book does, they’ve got to start from the beginning. Rita makes this statement in her introduction, that for her, Kronos was started at the end of 1952 or the beginning of 1953, and from that date, Gombrowicz reconstructed his past. Even to his birth and even to…

His conception?

JERZY JARZĘBSKI

Born in 1947, modern Polish literature critic and researcher, essayist, professor of Jagiellonian University in Kraków. Winner of many prestigious prizes. Polish Academy of Sciences and Polish Pen Club board member. Editor, author of the afterword and co-author of footnotes in Kronos.

KS: I’m not sure about his conception.

JJ: Knowing Gombrowicz, it might be interesting for him, how it happened and when.

Sounds like Laurence Sterne and the first page of Tristram Shandy.

JJ: Which was probably read by Gombrowicz, though there are no testimonies. He could have read it in French.

Any question about the validity of publishing Kronos at this time?

KS: I’m happy it is out. There were so many rumours about it, it’s better to have it public. I’m glad that Rita agreed to do it, and I’m proud of her decision, because I know it’s not nice. There are things that I agree with her are painful.

JJ: Especially because Gombrowicz is not quite right in his description of her. She did a lot for him and it’s visible, even from Kronos.

KS: Also, we are living in times of celebrities. If they can make a celebrity out of Gombrowicz the publisher will be very happy! (Laughter) Kronos reminds me of the private diaries of Marilyn Monroe. It was not a biography, it was her notes, from different years.

As a personal accounting? That’s the impression Kronos makes.

KS: It was not a Kronos, which is very chronologically ordered. Just her notes about her house, about visiting somebody, then a poem, a recipe for a chicken or a turkey, or something about her sadness. Very short lines.

JJ: Okay, but the biography of Marilyn Monroe is mysterious. He was a mythical person, but not as much as Marilyn Monroe.

KS: I’m talking about the kind of notes and kind of book.

The quality of self-observation?

KS: Self-observation, yeah.

How does that quality function in Kronos and in his Diary?

JJ: There’s a basic difference between the Diary and Kronos. The Diary is something that is created by the author. Kronos is something that writes itself, then Gombrowicz is reading his biography. He reflects about his fate, his sense of his biography. But it is ready, so to say, before he switched on his reflections. He collects facts, then reads the text and makes a summary of the year, and says how the year was for him.

The Diary is not a diary, in fact, not so much about life. It’s as much of a diary as the writer’s diary of Dostoevsky.

KLEMENTYNA SUCHANOW

Editor, translator, author of Argentyńskie przygody Gombrowicza (Gombrowicz’s Argentinian Ventures, 2005) and Królowa Karaibów (The Queen of the Caribbean, 2013). She does both academic work and journalism. Co-author of footnotes in Kronos.

KS: It’s a kind of creation. It’s like cooking, taking different ingredients from here, from there.

JJ: He confabulates. For instance, there’s a very nice essay about his visit in Stockholm. He never was in Stockholm. (Laughter) The essay is about Swedish aristocracy.

KS: I’m sure he had that from Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, who was going there and they had a common friend, Señora Quintana, with whom Iwaszkiewicz was in love. Her husband was in Stockholm as an Argentinean diplomat. Witold took that experience from their table talk.

He maintained Kronos for the similar years to the Diary. Are the two works complementary?

JJ: Kronos is definitely more full of facts.

KS: It’s all facts, facts, facts. A listing of facts, actually, put in some order. There are some things that we know from the Diary that are in Kronos, like his visits to Mar del Plata or Cordoba in Argentina.

JJ: Sometimes in the case of Kronos we know that something that was described in the Diary as fact was a cuento, Spanish for short story. Like in the case of the story of Simon’s daughter.

The little girl who was dying…

KS: Yes, but in the Diary, I don’t take that as a fact.

JJ: Me too. But there was no proof. And in Kronos you have it. It’s simply named: cuento. And anecdotes, like Gombrowicz describing lunch with Maurice Nadeau and Geneviève Serreau as something very, very distinguished, a fantastic menu, etc. Nadeau later asked him why. They ate lunch in a simple restaurant, it was an ordinary menu. And Gombrowicz answered “Okay – but it was good for my conception, I needed something about eating.” Nadeau couldn’t understand the way Gombrowicz creates, constructs the situations. He exaggerates in a special way.

KS: For his literary needs! He’ll make things up, even names. There’s one woman he recalls as “the one with stinking feet.” He’s makes annotations about his lovers that are sometimes pretty funny. Like “the one who didn’t want to” or “the one who didn’t like to be raped”. But that shows the obsession of reporting everybody even if he doesn’t know the name, he put’s something, a description.

JJ: For the report. (Laughter)

KS: Some people he’s meeting in Kronos we know, some we don’t know. And there are things that you can enjoy. One name I found among his lovers there are, you know, a thousand of names of those boys, and girls sometimes, not so much girls as boys of course… But there’s a moment when the name Antonio appears in his erotic life. You have to know that there’s a distinction in the manuscript pages, graphically, between his erotic life and current life. So Antonio was on the marginal column for lovers, appearing in 1954. Then in October, Antonio’s mentioned as performing in Teatro Colón, the Buenos Aires opera house.

I thought okay, if this Antonio at the Colón is the same guy, it’s becoming more real – so let’s look for an Antonio who was performing at Teatro Colón in 1954. And I found the Spanish dancer Antonio el Bailarín, who was living in Argentina for some time, he’d played in Hollywood movies, with Rita Hayworth and Judy Garland. He’s staying the whole year in Argentina in 1954, performing, rehearsing with his company. He was bisexual too, he had affairs with different movie stars then admitted at the end of his life in a book interview that he had homosexual experiences. I’m not saying it’s him, we’ll never know, but it sounds quite probable.

From Kronos, can you tell when an affair was serious?

KS: There is at least one case in the Argentina period, Aldo. Witold is very strongly attached to him. He looks like he’s really in love. I think it’s a question of sex and love, and not only sex. Rita has said Witold told her he had one person in Argentina with whom he was really in love.

JJ: What about people like Mariano Betelú? Gombrowicz was very much involved in Betelú’s career, and in his love affairs. He paid a stipend to Mariano.

KS: I didn’t find anything in Kronos that could allow me to say they had sex. I still remember Juan Carlos Gómez saying “Oh, it was because they had those dirty relations, but with me, it was purely intellectual.”

JJ: Yes, yes!

KS: If in the case of Gómez we say, or he would say, that it was intellectual, maybe in the case of Betelú it was just sentimental, and in the case of many, many others, it was sexual. Just sexual. Nothing else.

One problem that arose was that sometimes he’s saying muchacho, boy in Spanish, or chico. Sometimes he’s using muchacha, chica, a girl. But sometimes he’s using an abbreviation, and he’s writing “ch.”, which can be chico, and can be chica. So sometimes we don’t know the gender.

JJ: Okay, sorry, one moment. There’s an important piece of information in the European part of Kronos where he says that Rita was his first woman in twenty years.

KS: But these abbreviations start in the 1940s. He and Rita met in 1964 but if he’s saying to her “about twenty years or something like that,” it’s not the exact number of years. And there is some mention about some Andrea and Carlota in the 1950s.

JJ: Yes, he hated numbers. And maybe numbers hated him. He couldn’t add two and two, he always got it wrong. Yet he believes in a mystical value of numbers, it’s extremely funny. At the beginning of my part of Kronos, there is a calculation of the days he passed in Europe and then the days in Argentina. And he makes a mistake of about seven years! He’d been afraid of his math teacher at school.

KS: What’s bad about Gombrowicz, I have to say, is that he’s using very bad words and descriptions of women. Maybe that’s the view of the man’s world before the war. But words he’s using to describe women he’s having love with – er, sex with – are not pleasant. You have different words you could use to describe a woman, if you don’t use kobieta or dziewczyna or something like that, woman or girl. But he’s using kurwa, dziwka all the time: whore. It’s that very ugly vocabulary from – his older brothers? And he was a very sensitive guy, actually a weak person, and if he’s using those words, I don’t like to think about others, the stronger ones.

JJ: In that social circle I think that it was possible, for people who belonged to the land-owning class.

KS: Even in Argentina he’s using those words, sometimes puta, putita – which sounds actually neutral. But those Polish words in Argentina, being used by him at 40 or 50 years old? Rita’s always saying that he was a gentleman. But it was the kind of Polish gentleman who kisses a hand then uses humiliating vocabulary.

For me Kronos is one big obsession, an amazing obsession, an incredible, courageous vivisection of human life and its complexity. I wish we had more of such truly human pieces in literature. May the discussions it provokes help end the hypocrisy.