The founding myth of underground Polish jazz is incorrigible. The most outstanding veterans of the scene, Tomasz Stańko and the late Andrzej Przybielski both present the same version of the story. In the latter half of the 1960s, Władysław Jagiełło performed in Swedish bars, forming a duo with a black organ player who smoked weed with a passion. “He showed up in a white Lincoln full of stuff so good that our eyes almost popped out of our heads,” says Przybielski, recalling Jagiełło’s return to Poland. It’s hard to resist the implication that that event was what pushed Warsaw’s exploring jazz musicians down the road of free jazz. “Back in our quintet days I would drop by Władi’s place to light one up, and we’d walk to the Medyk to jam,” recalled Stańko.

Medyk on Oczki St. and Hybrydy on Mokotowska St. were Warsaw’s top modern jazz clubs at the turn of the 60s and 70s. It was from there that Stańko’s quintet set off on its increasingly bold improvisational journeys, and it was there that Jagiełło’s music underwent its metamorphosis. The latter, a drummer belonging to the first generation of Polish jazz musicians, active on the scene since its inception in the 1950s, was the founding member of the band Sesja 72. The group’s lineup featured musicians who would set the tone for the experimentation of the 1970s: trumpeter Andrzej Przybielski, bassist Helmut Nadolski, and pianist Andrzej Bieżan. “He used to be considered one of the best dixieland and swing drummers, and then the only thing he was interested in was avant-garde and free jazz. He was the terror of jam sessions,” recalled Marek Karewicz in Jazz Forum magazine, in an article commemorating Jagiełło, who died in 2009. This terse observation summarize the ostracism experimenters experienced at the hands of the Polish jazz scene. It’s no wonder that at his last concert, held in the early 90s at Akwarium, Jagiełło performed with reggae rockers Darek Malejonek and Robert Brylewski. It wasn’t the first or the last time the paths of Polish underground jazz and punk would cross. Stańko survived and thrived by breaking out onto the German scene. Jagiełło and Przybielski (the former passed away in 2009, the latter in 2011) could barely make ends meet in their old age. They left behind few recordings. The Oleś brothers have promised to complete a project that would document Prybielski’s compositions. One wonders what happened to the legacy of Jagiełło, who was so meticulous about saving his sheet music?

From Cage to punk rock

At the intense turn of the 60s and 70s, another crowd unassociated with jazz appeared on the scene: hippie freaks, performance artists, avant-garde offshoots of the academic world interested in improvisation. It was there that the band Grupa w Składzie was formed and played its first show, a concert at Poland’s first hippie commune in the town of Ożarów. The group was founded by Milo Kurtis (later co-creator of the bands Osjan, Manaam, and Izrael), Andrzej Kasprzyk, and Jacek “Krokodyl” Malicki. The lineup evolved over time, performing later shows with a whole plethora of restless Warsaw bohemians, particularly Andrzej “Amok” Turczynowicz and Andrzej Zuzak (who later resurfaced as activists on the proto-punk scene; Amok would go on to found his own groups, including Grupa Swobodnej Improwizacji in 1977), as well as exploring musicians, among whom were Bieżan, Przybielski, and Nadolski. In 1971–1974, Grupa w Składzie won distinctions at the legendary Contemporary Youth Music Festival in Kalisz (the first edition of which, held in 1969, was known as National Avant-Garde Beat Festival) and the Jazz on the Odra Festival; it was intensively active in gallery circles and took part in multimedia performances. A chronicle of these events — which place the band in the context of 1970s Polish conceptual art and the influence of the Fluxus movement – can be found in the booklet accompanying the anthology Grupa w Składzie, published by Trzecia Fala, which constitutes the band’s only published material. The archival recordings collected in the release depict a highly interesting and original phenomenon.

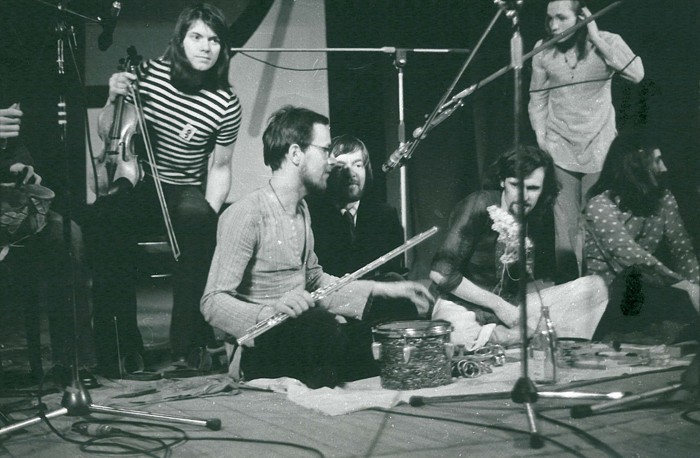

Grupa W Składzie, from the right: Witold Popiel and Jacek Malicki, photo: W. Popiela archive

Grupa W Składzie, from the right: Witold Popiel and Jacek Malicki, photo: W. Popiela archive

Grupa w Składzie managed to get by without a rhythm section, relying instead on guitars, a double bass, a bouzouki, flutes, a saxophone, a bassoon, and percussive instruments. An important role was played by vocal harmonies, which revealed an elusive Eastern feel. The band called their art “intuitive music.” The amorphous poetics of their sound-centric improvisation is far removed from cold, conceptual avant-garde jazz, and speaks with a rootsy kind of energy. Grupa w Składzie’s music has the aura of a catacomb ritual. Its character is best described by Krokodyl’s authorial commentary: “Listening or reciting poetry was far from our intent, though we were conscious of Homer’s epics, as mythical as they were and as complex was their provenance, but they did come from the memory box of the mind, not unlike the slam poetry of today. We were more drawn by child-like babbling, hitting drumsticks with no rhythm, and completely primordial tapping, because we wanted to discover the beginnings of music, just like the cave paintings of Lascaux and Altamira were discovered.”

Grupa w Składzie anthology, Trzecia Fala 2014If we were to look for comparisons, the more abstract “spaces and sounds” of the early Art Ensemble of Chicago would be most apt. But Grupa w Składzie was closer to John Cage than it was to jazz. Footage from their Kalisz concerts gives us an idea about the sound experiments conducted by the musicians who, using amplifiers and reverb, achieved effects similar to the “cosmic music” of the German rock scene. The record also feature a montage of prepared tape which was intended to be used at multimedia performances, during which Grupa w Składzie played reel to reel tape players rather than instruments. Sound collages gleaned from the radio and television, echoing the hits of the People’s Republic of Poland, contrast sharply with the group’s improvisation style and foreshadow the experiments of industrial music. The surprising finale of the record features a recording made in 2012. Grupa w Składzie is once again playing concerts. There’s another semi-mythical group of autodidacts from the early 70s waiting to be discovered: Warsaw’s Tlenek Jazzawy, formed by future punk and new wave heroes, saxophone player Tomek “Men” Świtalski and Jasio “Grzmot” Rołt.

Grupa w Składzie anthology, Trzecia Fala 2014If we were to look for comparisons, the more abstract “spaces and sounds” of the early Art Ensemble of Chicago would be most apt. But Grupa w Składzie was closer to John Cage than it was to jazz. Footage from their Kalisz concerts gives us an idea about the sound experiments conducted by the musicians who, using amplifiers and reverb, achieved effects similar to the “cosmic music” of the German rock scene. The record also feature a montage of prepared tape which was intended to be used at multimedia performances, during which Grupa w Składzie played reel to reel tape players rather than instruments. Sound collages gleaned from the radio and television, echoing the hits of the People’s Republic of Poland, contrast sharply with the group’s improvisation style and foreshadow the experiments of industrial music. The surprising finale of the record features a recording made in 2012. Grupa w Składzie is once again playing concerts. There’s another semi-mythical group of autodidacts from the early 70s waiting to be discovered: Warsaw’s Tlenek Jazzawy, formed by future punk and new wave heroes, saxophone player Tomek “Men” Świtalski and Jasio “Grzmot” Rołt.

Grupa w Składzie, photo: unknown author, Trzecia Fala promotional materials

Grupa w Składzie, photo: unknown author, Trzecia Fala promotional materials

Music at the Remont

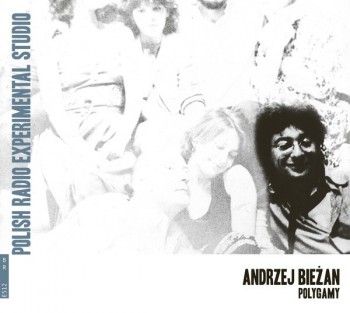

Andrzej Bieżan was a classically-trained composer, but he opted to go down the path of a musical iconoclast. Similarly to Grupa w Składzie, he described his art as intuitive music; what mattered to him was the moment of creation, the here and now. In his view of “music now,” what mattered was collective meditation, improvisation, sound experiments, and performance situations. His compositions for plates, cups, saucers, and glasses have gone down in history, as has a piece inspired by whale songs and the tubmaryna, an invention of Bieżan’s that took the form of a two-meter-long, single-string instrument with roots in the Renaissance, equipped with a reverb box that employed two tape players on a feedback loop. Bieżan appeared in countless bands in the late 70s and early 80s, blurring the lines between composition and improvisation, and electronic music and jazz. Muzyka Intuicyjna, Super Grupa Bez Fałszywej Skromności, Cytula Tyfun da Bamba Orkiester, Niezależne Studio Muzyki Elektroakustycznej are some of his most important projects. He played at the Warsaw Autumn Festival and Jazz Jamboree, put on a Stefan Themerson opera, and recorded at Polish Radio’s Experimental Studio.

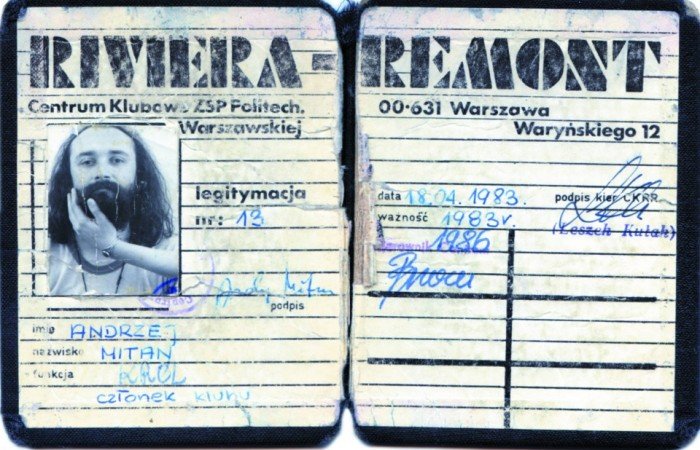

Polygamy by Andrzej Bieżan, Bołt Records 2014Polygamy, a two-record anthology including a monograph devoted to the artist, published by Bołt Records, appears to be a true revelation of the impressive capabilities of this forgotten individualist, who died tragically in 1983 at the young age of 38. The album features the first reprints of recordings from the legendary “Klub Muzyki Nowej Remont” (“Remont New Music Club”) series. The 1984 LP Miecz Archanioła (“The Sword of the Archangel”) was the first title in the series. The man behind the project, Andrzej Mitan, saw the release of the album to its finish in order to honor the memory of Bieżan. Eight more albums/art objects were published after Miecz Archanioła.

Polygamy by Andrzej Bieżan, Bołt Records 2014Polygamy, a two-record anthology including a monograph devoted to the artist, published by Bołt Records, appears to be a true revelation of the impressive capabilities of this forgotten individualist, who died tragically in 1983 at the young age of 38. The album features the first reprints of recordings from the legendary “Klub Muzyki Nowej Remont” (“Remont New Music Club”) series. The 1984 LP Miecz Archanioła (“The Sword of the Archangel”) was the first title in the series. The man behind the project, Andrzej Mitan, saw the release of the album to its finish in order to honor the memory of Bieżan. Eight more albums/art objects were published after Miecz Archanioła.

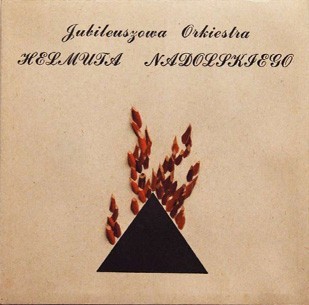

“Klub Muzyki Nowej Remont” albums are now in the collections of the world’s top modern art galleries, alongside the phonographic projects of Cage, Warhol, and Dubuffet. Each vinyl record was published in limited editions of one thousand copies, in hand-made record jackets designed by a great number of outstanding artists. The creation of the jacket was in itself an unprecedented process. The cover of Jubileuszowa Orkiestra Helmuta Nadolskiego, designed by Andrzej Szewczyk, was plastered with shavings from red crayons. Other projects required the use of such materials as tablecloths and fishing nets. The recording of Mitan’s “Ptaki” involved forty parrots borrowed from a pet store for the three-day session. This collective work with a happening aura excellently conveys the expressive style of the circles tied to the Remont club, which as a gallery, workshop, and concert space was likely the most important location on the map of Polish alternative culture in the latter 1970s. Its musical side was home to the avant-garde, underground jazz, and Poland’s earliest punk rock acts. Good introductions to the club’s potential include the book Obok (“Next”) by Mirek Makowski, published in 2012 by Manufaktura Legenda, and the material collected on the website of Andrej Mitan, the poet and performer who was one of the leading activists behind Remont in its peak years.

photo: courtesy of Dobrochna Badora

photo: courtesy of Dobrochna Badora

It’s too bad that Mitan isn’t interested in re-releasing “Klub Muzyki Nowej Remont,” as he believes (perhaps correctly) that those recordings should exist as unique art objects. On the other hand, the series included the best documentation of the work of two of the leading figures of Polish underground jazz in the 1970s, the albums Jubileuszowa Orkiestra Helmuta Nadolskiego (“Helmut Nadolski’s Jubilee Orchestra”) and Andrzej Przybielski’s W strefie dotyku (“In the Zone of Touch”). These records contain fascinating sonic poems that drift between jazz and contemporary music, combining free jazz with the sound of live electronics. They come across as Stockhausen-inspired electroacoustic jazz that is Europe’s answer to America’s funky electronic jazz boom. Britain’s improvisational musicians followed a similar path with projects that revolved around such names as Derek Bailey, Tony Oxley, and Evan Parker. The existence of a group of Polish musicians who were no less creative is a fact that should not go unnoticed. Samples of this style can be found on Polygamy, which includes a fragment from the record by Nadolski; a composition by Bieżan titled “Isn’t It?”, and the record Kiedy umiera człowiek (“When a Man Dies”), published by Trzecia Fala. The last album is a video recording of a Mitan performance put on with Jubileuszowa Orkiestra.

Helmut Nadolski’s Jubilee Orchestra, Alma Art 1984Mitan, a vocalist endowed with a characteristic falsetto, gravitated towards elaborate forms that combined poetry and music. His most important project in this style was Księga Hioba (“The Book of Job”), based on translations by Czesław Miłosz. He staged the performance with Super Grupa Bez Fałszywej Skromności (Bieżan, Nadolski, Przybielski, and another 1960s jazz veteran, drummer Janusz Trzciński) at a Solidarity-sponsored concert held at the 1981 Jazz Jamboree. Plans for another show, which was supposed to be held at the Gdańsk Shipyard, were cut short by the imposition of martial law. In response to the shutdown of concert life, Mitan developed a low-key project titled “Psalmy” (“Psalms”) which toured churches and galleries. A new plane of expression was created by the homespun Niezależne Studio Muzyki Electroakustycznej, a collaboration between composers Krzysztof Knittel, Paweł Szymański, Stanisław Krupowicz, Andrzej Bieżan, Mieczysław Litwiński, and Tadeusz Sudnik.

Helmut Nadolski’s Jubilee Orchestra, Alma Art 1984Mitan, a vocalist endowed with a characteristic falsetto, gravitated towards elaborate forms that combined poetry and music. His most important project in this style was Księga Hioba (“The Book of Job”), based on translations by Czesław Miłosz. He staged the performance with Super Grupa Bez Fałszywej Skromności (Bieżan, Nadolski, Przybielski, and another 1960s jazz veteran, drummer Janusz Trzciński) at a Solidarity-sponsored concert held at the 1981 Jazz Jamboree. Plans for another show, which was supposed to be held at the Gdańsk Shipyard, were cut short by the imposition of martial law. In response to the shutdown of concert life, Mitan developed a low-key project titled “Psalmy” (“Psalms”) which toured churches and galleries. A new plane of expression was created by the homespun Niezależne Studio Muzyki Electroakustycznej, a collaboration between composers Krzysztof Knittel, Paweł Szymański, Stanisław Krupowicz, Andrzej Bieżan, Mieczysław Litwiński, and Tadeusz Sudnik.

The rise of the Częstochowa scene

If we were to look for bastions of underground jazz outside of Warsaw at the time, the unlikely city of Częstochowa would turn out to be the most important scene. The city of the Black Madonna might seem very distant from the world of avant-garde jazz, but nothing could be further from the truth. The members of the band Tie Break are unanimous in their assertion that the faltering melodies of pilgrimage orchestras were among their earliest musical inspirations. Years later, these devotional songs would influence the original style of the band, which has reappeared after a long hiatus and continues to surprised audiences with a fresh perspective. Slated for release in 2014 is a five album box set containing all the classic Tie Break recordings along with material by their rock mutation Woo Boo Doo. It’s no surprise that they call themselves “the Tie Break family”: since the late 70s they’ve formed an art collective of musicians and painters who have given us such important figures as Ziut Gralak, Janusz “Yanina” Iwański, and Mateusz and Marcin Pospieszalski. Tie Break broke out onto the broader scene thanks to their victory in the 1980 edition of the Jazz Juniors competition. At the time, their music was described as “punk jazz.” And they were in fact the first Polish group to offer an answer to the thriving New York loft scene and harmolodic no-wave funk. Raised on the Beatles, the Stones, Coltrane, and Miles Davis’ electric work, they had also done their homework on the ethnic music of Asia and Africa. And what lied behind the power of their expression was their tribal aura, emphasized by their signature vocals in a made-up language.

Tie Break was joined in the 80s by the Kielce scene, which featured the band Stan d’Art, Włodzimierz “Kinior” Kiniorski, and Sarandis Juwanudis, who had previously collaborated with Jerzy Grotowski. The musicians in Tie Break quickly became a pillar of the intercity underground jazz scene of the 80s, performing in such groups as Free Corporation and Young Power, and later backing and defining the style of Stanisław Soyka’s bands, beginning with the radical and forgotten Sfora and then Voo Voo. But that’s a whole different story.