Piotr Dumała’s feature-length debut is a manifestation of great courage. In the opening decade of a new century, the director follows in the footsteps of the early 20th-century pioneers, resorting to black-and-white film and the silent movie convention. Walking with the two main characters through The Forest confirms us in the conviction that what we’re dealing with is neither the author’s extravagance nor an accident. It’s possible that this story couldn’t have actually been told otherwise. Words would have been superficial here and color would naturalize the supernatural. The story told by Dumała and his cinematographer, Adam Sikora, is about a rite of passage in which the paroxysm of life coincides first with the effort, and then the peace of dying.

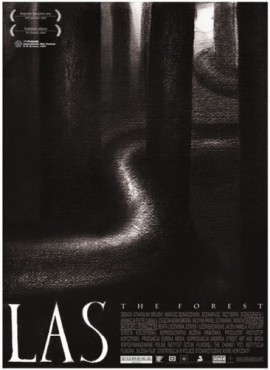

The Forest, dir.Piotr Dumała, Poland, 2009

The Forest, dir.Piotr Dumała, Poland, 2009

This surprising unity is built in dramatic silence, within the rectangle of a small country cottage room (similar to that in Nostalghia, where “under the wall stood a stove, a table, stools of various sizes, and a cot with crumpled sheets”), in the grays of semi-darkness, in the solitude and weariness of two travelers, and thus in a horizon capped by the treetops. It culminates between fire and water: in a high flame that gradually becomes smaller, shrinks and eventually dies away at the bottom of the screen, only to return, like a palimpsest, in the underwater flow of the secret, incredible finale.

This is beautiful but by no means easy. Dumała abandons traditional narration, especially in the forest sequences, opting instead for pictorial suggestion and musical rhythm. Both of these dominants, though organically connected, require our consent to non-conceptuality. Like an anti-naturalistic painting, a musical piece is the opposite of discourse.

Inner logic supplants the conventional notion of cause and effect. Associations replace syntax-based disquisitions. The concrete remains intact but peculiarly transformed. Entering The Forest – so sensual and biological – assumes the ability to abstract. This is no place for the tone-deaf.

The author demands the audience’s absolute concentration. A moment of inattention would deal a deadly blow to the viewer’s perception of The Forest. And, to a certain extent, to the ambition of Dumała himself. There exists, after all, feedback between the two. He could have encapsulated this anti-narration in a half-hour etude. Yet, convinced he wouldn’t be able (or have time) to say it all, he made it a full feature. Dilemmas like this are characteristic of such projects: how does one summarize that which by definition resists summarization?

Within classic film narration, few authors gave precedence to the inner state rather than cinema’s distinctive, narrative, element. They faced all kinds of temptations and encountered all kinds of obstacles. Robert Bresson found the spiritual in the simplest gestures and ordinary objects. There was impressive consistency in that but also an underlying concern over the comprehensibility of the story. Hence the paradox in the ascetic work of off-screen verbal commentary. Hiroshi Teshigahara in Woman in the Dunes went even further than Dumała in reducing space. The protagonists of the Polish film live in the illusion that the path will finally lead them somewhere, although the forest is a labyrinth. Teshigahara reduced the existence of two people to neverending imprisonment in a sandy cage; the viewer shared their sense of claustrophobia. Jean Cocteau, hailed a poet of the screen by his contemporaries, transformed reality with means of expression that only seemed magical in his times. In the process, he manifested his ego, making it a partial subject of his work. Andrei Tarkovsky closest approach to the mysterious essence of things was probably in Stalker, rather than in the beautiful but unintentionally egocentric landscapes of Sacrifice or Nostalghia. Cinematic searches for the philosopher’s stone are usually fraught with self-admiration.

(New Horizons Association)Dumała, no less subtle than the other ones, remains unique in his peregrinations, shunning any exhibitionism, any displays of his artistic ego. The Forest stands out precisely because of its emanation of empathy. Filial love is a basic figure of empathy. Family roots are a prefiguration of one’s relationships with the Other. We don’t know the history of the son’s relations with his father. There are signs of patriarchy in them: in the initial setup of the roles, in the lofty and at once hermetic metaphor of filicide or – in contrast – the wonderful, discreetly amusing scene of the supper by the fire. What is more important than those biographical tropes, however, is the turning point: the moment when the young man really notices the old one, the healthy one notices the sick one, the needy one finds a tender helping hand.

(New Horizons Association)Dumała, no less subtle than the other ones, remains unique in his peregrinations, shunning any exhibitionism, any displays of his artistic ego. The Forest stands out precisely because of its emanation of empathy. Filial love is a basic figure of empathy. Family roots are a prefiguration of one’s relationships with the Other. We don’t know the history of the son’s relations with his father. There are signs of patriarchy in them: in the initial setup of the roles, in the lofty and at once hermetic metaphor of filicide or – in contrast – the wonderful, discreetly amusing scene of the supper by the fire. What is more important than those biographical tropes, however, is the turning point: the moment when the young man really notices the old one, the healthy one notices the sick one, the needy one finds a tender helping hand.

The most important things in The Forest take place around the seat to which the paramedic lashes the numb, dying old man. Both then fight for their lives. Seemingly, it’s the father’s survival that’s at stake. Perhaps the son’s life is at stake, too. One day the desperate loving struggles come to an end. No longer must they struggle through the woods, tiptoeing around carefully, nervously checking the compass. The cords become redundant, a useless stool stands opposite an empty bed. The sudden idleness makes you choke. A terrible silence sets in.

(New Horizons Association)As time passes, the importance of The Forest will be increasingly evident. I don’t think there is a point in arguing whether this film is an absolute masterpiece or rather an intriguing experiment. It’s hard to interpret an utterly personal statement in aesthetic terms. The Forest was born as a necessary confession and is a niche work in the literal sense. Dumała confessed: “Facing the impending death of my parents … was a discovery of a new sphere of communion, a fundamental one. It’s incredible when you realize that the body has its beginning and end, you can feel it when you feed someone and see their excretions. It’s like with a child. A person exists for a certain period of time and reaches his physical end, like a machine.”

(New Horizons Association)As time passes, the importance of The Forest will be increasingly evident. I don’t think there is a point in arguing whether this film is an absolute masterpiece or rather an intriguing experiment. It’s hard to interpret an utterly personal statement in aesthetic terms. The Forest was born as a necessary confession and is a niche work in the literal sense. Dumała confessed: “Facing the impending death of my parents … was a discovery of a new sphere of communion, a fundamental one. It’s incredible when you realize that the body has its beginning and end, you can feel it when you feed someone and see their excretions. It’s like with a child. A person exists for a certain period of time and reaches his physical end, like a machine.”

I’ve never talked to the author of that confession, but his words are the reason for the profound and non-verbal bond that exists between us. So there are two of us? Even if there are several thousand more, it’s not millions of sympathizers. For many, “mother”, “father”, “brother” or “daughter” are just designates of concepts. Making it easier to put one’s relations with the Other in order but not identical with actual experiences. Putting things in order but never hurting. It’s only a personal experience that lets them into your bloodstream.

The uniqueness of the situation described in The Forest is inextricably intertwined with an intimate tone. Two different, not always identical, perceptions of our experience overlap here: the existential and the artistic. It’s as if the author, intuitively, almost groping in the dark, was touching a liminal point beyond which nothing can be seen. I doubt whether Piotr Dumała will ever want or be able to tell a similar story in film. Such things happen only once. An iron bed, stripped and bare, the traces of bedsores fading away, the warmth evaporating; tomorrow, in a stranger’s eyes, it will become but an anonymous piece of furniture. The time defined by The Forest’s motto, the time invalidated by the father laid in his grave, disperses slowly and delicately, like light in clear water.