What don’t we know about Józef Robakowski? That was pretty much the question I had in mind when I left for Łódź, where the artist has spent nearly half a century. We met at the Exchange Gallery – a cult hangout for fans of the international avant-garde of the 1980s.

We were supposed to talk about his retrospective at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, but we spent nearly five hours talking about something else. And then suddenly my interlocutor had to run because we spoke for so long he was already running late for his next appointment. Before leaving he puts a collection of “intervention texts” and a copy of Antoś Rozpylacz – a poem by Wacław Antczak – into my backpack. “Everything’s in there” – he says. “The rest you can find on the internet.”

MY OWN CINEMA

Monographic exhibition of works by Józef Robakowski, curator: Bożena Czubak, Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw, open till 23 September 2012.

You can watch some of his works online on the website of Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw.

“I want to tell you all that art is energy!” – screams Robakowski as he shoots out of the water (The Energy Manifesto!, 2003). Then we study the splash of the resulting geyser in slow motion. The piece represents the essence of Robakowski’s actions – a clear and simple psychophysical message condensed down to a single image thanks to technology. But as we continued our conversation, I was struck by something else: his belief in art as an independent value of the highest order. I tend to think that Robakowski’s basic attitude towards life is that of extreme non-conformism. His entire output is subordinated to one, single utopia: to make an artistic gesture yours alone and independent – against all trends and fashions. It’s accompanied by the destruction of dogma and demarcations encountered at the intersection of cinematography and art.

Józef Robakowski, The Energy Manifesto, 2003, photo: courtesy of the artist

Józef Robakowski, The Energy Manifesto, 2003, photo: courtesy of the artist

Cleaning the Film

To start off on the right foot I ask about the pieces that he created under the auspices of the Workshops of the Film Form. It was mostly constructivist – experiments with film as a medium; an analytic quest for its most basic essence. In practice, it meant eliminating the plot, reducing the soundtrack, doing away with editing. Some of these films were even made without a single camera.

An excellent case study in this instance would be Test 1 (1971), created through manual perforation of film stock. It’s basically a visual and acoustic reflection of physical intrusion into the structure of the stock. This piece is impossible to “watch” or “decipher” – like an abstract sculpture it stimulates our perception apparatus using spatiotemporal rhythms. The grates and rasps irritate our imagination, while blinding flashes hit our eyes, resulting in the physiological phenomenon known as an afterimage. An absolute cinematographic minimum. What’s interesting, even at this basic level the author can do something to distinguish his efforts from similar attempts – one simply needs to compare the efforts of 22 different people to see that this is true (22x, 1971).

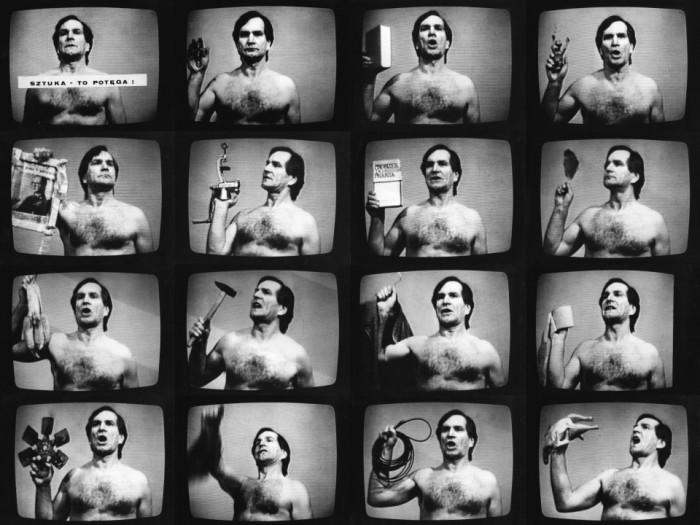

Józef Robakowski, Art is Power, 1985, photo: courtesy of the artist

Józef Robakowski, Art is Power, 1985, photo: courtesy of the artist

From all this a question arises: how should we look at all this? In his excellent study, Łukasz Ronduda situates these realisations in the context of Jan Świdziński’s contextual art. According to this interpretation, they would be “blank characters” – purely physical object that acquires meaning through “immersion in discourse”, i.e. via open and creative language play initiated by the audience.

Robakowski, however, who was Świdziński’s long-time collaborator, distances himself from that sort of interpretation. This question remained elusive during our conversation so I brought it up later, in an email. Robakowski responded: “The theory-practice split would be a good hint. We had a WORKSHOP concept of how to function in the field of art. Świdziński quickly ascended to the theoretical level and never left.” The goal of the workshop-oriented splinter wasn’t to create conceptual props, it was to achieve measurable practical effects – a permanent revision of the perceptual customs of the audience.

The idea of “clean cinema” fits perfectly with the Łódź avant-garde represented by Kobro and Strzemiński, who Robakowski often brings up. But if we want to find the source of that idea, we need to be looking elsewhere. “You know what, I have recently started to ponder that myself…” – without interrupting the conversation, the artist moves to the hallway where the bookshelves are. After a short while he hands me a copy of Karol Irzykowski’s The Tenth Muse — it’s worn down and a multiple fragments are highlighted with a pen. “That’s what it all started with” — he says. Obediently I start to leaf through the copy. And I soon discover that already in the 1920s did Irzykowski posit that the essence of cinema lies in “optical magnification of the surface of the world” and in the “exposure of light in a system of lens.” The trouble is that for more than half a century nobody understood what he meant.

A Gang of Buffoons and the Dadaists

The output of the Workshop of the Film Form (WFF) turned out to be a worldwide sensation. After the group’s appearance at festivals in Edinburgh (1972) and Knokke-Heist (1974), they were invited to festival all over Europe, including to the 6th, 7th and 8th edition of Documenta in Kassel. The artists quickly became acquainted with the leading personalities of the avant-garde movement. Soon thereafter, Łódź was visited by the likes of Joseph Beuys, Valie Export, Jan Dibbets, Jiří Valoch and Paul Sharits. Despite all of that, the artistic output was not truly appreciated in Poland, or — as Robakowski claims — it was disregarded by both the film and plastic arts circles.

Both the former and the latter looked down on the Workshop-affiliated artists with barely masked condescension. Filmmakers (including Wajda, Zanussi and Kieślowski) remained aloof, while the critics accused them of escapism from “the important issues of the era” and engaging in common gimmickry. When it comes to people representing the plastic arts, there is a famous letter penned by Wiesław Borowski, in which he calls an entire group of artists that had no ties to the Foksal Gallery “pseudo-avant-garde”, and claims that they represent “a clear and present danger to Polish culture” (Kultura, issue 12, 1975). When we bring the letter up, Robakowski does nothing to hide the resentment. As a consequence of the screed, he and many of his friends (including Natalia LL, Zbigniew Warpechowski and Andrzej and Ewa Partum) lost their shot at a feature exhibition, both at home and abroad. “Do you think that it was a countercultural movement?” — I tip-toe around the issue. “Of course it was” — Robakowski exclaims, nearly jumping up in his seat — “the Foksal people were simply afraid of having us as their competition.”

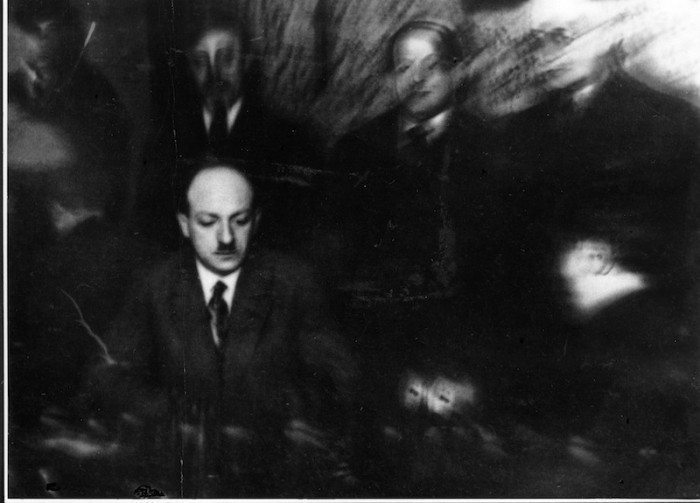

Józef Robakowski, Astral Photography, 1972 / dzięki uprzejmości artysty

Józef Robakowski, Astral Photography, 1972 / dzięki uprzejmości artysty

Alas, Robakowski and his group shared part of the blame for the situation. They constantly provoked and staged “interventions” – irreverent, ironic Dadaist gestures aiming for the deconstruction of established norms. Eventually, these actions became their most recognisable effort, unfortunately drawing away public attention from the true essence of their movement. The Workshop people dressed up as “ordinary people” and ridiculed the screenings of their own films, shouting: “Where’s the human element?!,” “Not on the eyes, man!,” and “What is this all about?” With equal gusto they mocked haughtiness and buffoonery of cinema’s visionaries and derided the pseudoscientific jargon of “sophisticated conceptualism”. The examples of the latter include “astral photography” — a series of supposed photographs of thoughts, captioned with invented comments. But the mockery achieved the opposite effect — instead of revising old patterns and establishing new dialogue, they only deepened the existing divides and made it easy for their opponents to justify their hostility towards the group.

But there is another, more mundane reason for their “exclusion”: they lacked the proper infrastructure to screen works that combined film and plastic arts. The Workshop people used 35mm film stock for their projects — archiving and screening that kind of stock required sophisticated equipment, unavailable to museum and art galleries at the time. Nowadays, everyone carries a multimedia archive in their phone — it’s hard to imagine how tough it was back then.

A Triumph of Mind Over Matter

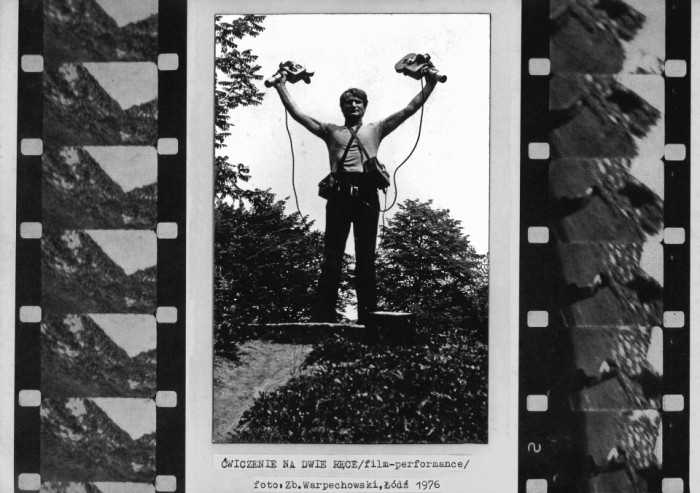

The archive of the Exchange Gallery, established by Robakowski in 1978, includes the works of Stażewski, Witkacy, Christ, Nam June Paik and many others. We spend a lot of time leafing through albums documenting the group’s operations. My attention is drawn to a picture from Robakowski’s An Exercise for Two Hands (1976) — the artist triumphantly picks the cameras up, like a gunslinger after a well-placed shot.

Józef Robakowski, An Exercise for Two Hands, 1976, photo: courtesy of the artist

Józef Robakowski, An Exercise for Two Hands, 1976, photo: courtesy of the artist

The biomechanical recordings descend from the early experiments of the WFF, to some extent, through negation. The artist was apparently fed up with filmic nature being soulless and too clean. Thus, he brought up another question: to what extent does cinema technology control the creative process, and to what extent is it subject to anthropomorphisation?

Contrary to the claims of Łukasz Ronduda, it’s not about the dialogue of two physical realities — the machinery of the film camera and the machinery of the human body. This materialistic interpretation goes fully against the spirit of Robakowski’s concept of art as idealistic — and indeterministic. In a way it’s also contradicted by other biomechanical recordings. Have you seen My Leg Hurts (1990)? Or the amazing I’m Going (1973)? We experience these works in a different way than we experience ordinary films — it’s like the video feed becomes a living organism, almost a person. That’s true empathy — we wouldn’t feel this way towards a machine.

The failures of WFF at home and its successes abroad have only radicalised Robakowski’s non-conformism. When the government tried to interfere with the editing process of The Live Gallery (1975), the artist wrote a letter to the Minister of Culture and Art, wherein he officially quit cinematography. Seven years later — a month after martial law was introduced in Poland — he also quit his job at the Polish National Film, Television and Theatre School in Łódź. These circumstances produced the “Personal Cinema” — a project that was political down to its very core; it was a testament of private struggles for the independence of artistic action, against the overbearing dullness of communist reality.

In this project, Robakowski shifted the focus from material and formal aspects of films and filmmaking to subjective and existential aspects of everyday life. He also started using a new medium — a video camera that he used as a notebook, “a way to remember myself, to record changes in mentality, biological expression, various whims, psychological tensions that came about because of the so-called reality” (a conversation with Danuta Ćwirko-Godycka, 1990). From My Window (1978–99) is an iconic example of the approach. Rodunda claims that the project was an ironic commentary on the language of denunciation and fears of surveillance. About Fingers (1982) is also an eloquent gesture of withdrawal — the short was a sort of autobiography of the artist “acted out” by the fingers of his right hand.

Art is Energy

The “Personal Cinema” series is still a work in progress — the exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Art features Polak mały (2010) and Concerto for the Head (2009) — featuring the artist’s cat in a stunning performance (!). But in the 1980s, Robakowski was still primarily focused on cinematography. Along with his WFF buddies, Robakowski organised multiple international artistic events in Łódź, including Construction in Process (1981), Artistic Pilgrimage (1983), two editions of Silent Cinema (1983–1984) and The Dungeons of Manhattan (1989). These events were emanations of the so-called Pitch-in Culture, an underground social movement that grew up around galleries organised in apartments in Łódź. Apart from the Exchange Gallery, there was the Carpet Cleaning Gallery and the Attic Gallery — the latter served as headquarters for Łódź Kaliska.

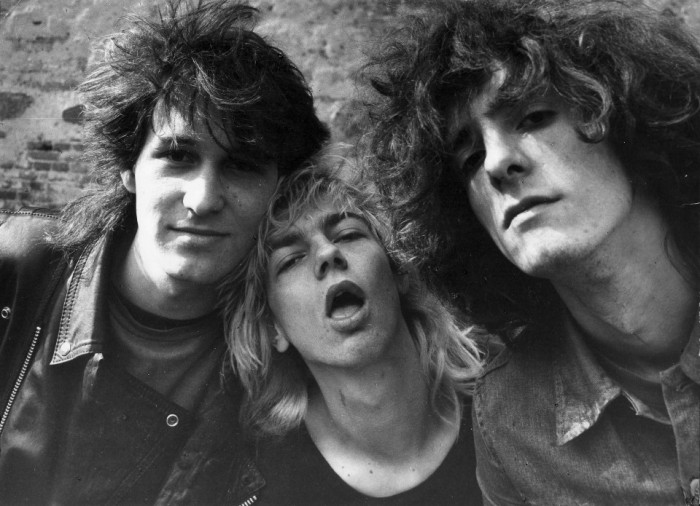

Moskwa – the band, 1986, photo: Józef Robakowski, courtesy of the artist

Moskwa – the band, 1986, photo: Józef Robakowski, courtesy of the artist

Robakowski also mentions that the Pitch-in Culture phenomenon was a collective act of intellectual and moral independence, an “art of self-defense” against the psychosis of martial law. But I was more interested in another turning point in his creative output – his fascination with punk culture and music. He was very glad that I brought that up. He immediately started talking about making music videos for the band Moskwa during the 1984 Jarocin Festival. The crowd was very aggressive towards him and someone shouted: “Hey, you with the camera, get the fuck out! You’re gonna get wasted once we get going!” He remained unafraid: “Nah, I’m staying.” Nothing had happened, “I crowdsurfed a little while after that and later recorded the pogoing kids” — Robakowski laughs at the memories.

He saw punk as a clean, primal, untainted and elemental — an authentic expression of rebellion and the only antidote to counteract the sad reality of those times. It provided a good contrast for the neo-expressionism movement — according to Robakowski, its Polish followers were irritatingly derivative, especially when compared to their German counterparts, plus it was promoted by the communist authorities as a kind of a fig leaf. Nowadays Robakowski thinks that this moment was a real turning point for him, it opened a new chapter in his artistic development — he left the realm of analytical art and made his home in the energetic art realm.

Wacław Antczak presenting a prop for Antek Rozpylacz film (1972), photo: courtesy of the artist

Wacław Antczak presenting a prop for Antek Rozpylacz film (1972), photo: courtesy of the artist

But was it a real breakthrough? Or was it — to paraphrase Wittgenstein — a turn around the “pivot of our real need”? I tend to agree with the latter, especially when I take Władysław Antczak into consideration – a man who Robakowski unironically calls his beloved master and whose poem he stuffed into my backpack. Antczak was a member of the lumpenproletariat, a tailor by trade, and a talented actor, violinist, poet, who also dabbled in melodeclamation — he had a tremendous influence on the WFF crew when they were still in college.

What was it about him that fascinated the young filmmakers so much? What did he have that the honoured professors lacked? I think Ronduda says it best: he had zeal, his work was completely unselfish, he had a creative approach to the world, lots of enthusiasm, and his artistic gestures were pure and sincere — all of which are values that are (nearly?) extinct in the professional art world.

The editorial staff and author of the article would like to thank Michał Jachuła from Arsenał Gallery in Białystok for his help regarding the article.

translated by Jan Szelągiewicz