Theodor Adorno notes that “embodying the objective spirit of an epoch in a single concept of ‘culture’ instantly betrays an administrative view-point, from whose superior perspective, the task is that of collating, distributing, valuing and organizing” - and he goes on to list the characteristic of that viewpoint: “Demands placed upon culture by administration are by their nature heteronomous: regardless of what form culture takes on, it must be judged according to norms not of its own, and having nothing to do with the value of the object, and everything to do with with some kind of abstract standards imposed upon in from outside.”

Fine martial arts

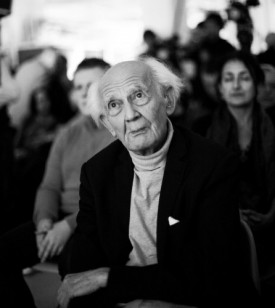

Zygmunt Bauman, photo Bartosz TrzeszkowskiBut as can be expected from such an asymmetrical social relationship, an altogether different sight must greet the eyes of those who experience this state of affairs from the opposite end – from the side of the managed, not the managers; and an altogether different conclusion would be drawn if the observers from the other end were to be permitted to form and pass judgements. We could then expect a panorama of unfounded and unwanted repression, and a verdict of injustice and lawlessness. From that other perspective, culture appears in opposition to management, and that because, as Oscar Wilde put it (provocatively, according to Adorno), culture is “useless”, or at least seen as such, as long as the (self appointed, and from the point of view of art, illegal) supervisors, hold the monopoly for laying down boundary-lines between usefulness and uselessness. In this sense, according to Adorno, “culture” represents the interests and demands of the particular, as against the homogenising pressures of the “general” – and “takes on an uncompromisingly critical stance towards the existing state of affairs, and its institutions.”

Zygmunt Bauman, photo Bartosz TrzeszkowskiBut as can be expected from such an asymmetrical social relationship, an altogether different sight must greet the eyes of those who experience this state of affairs from the opposite end – from the side of the managed, not the managers; and an altogether different conclusion would be drawn if the observers from the other end were to be permitted to form and pass judgements. We could then expect a panorama of unfounded and unwanted repression, and a verdict of injustice and lawlessness. From that other perspective, culture appears in opposition to management, and that because, as Oscar Wilde put it (provocatively, according to Adorno), culture is “useless”, or at least seen as such, as long as the (self appointed, and from the point of view of art, illegal) supervisors, hold the monopoly for laying down boundary-lines between usefulness and uselessness. In this sense, according to Adorno, “culture” represents the interests and demands of the particular, as against the homogenising pressures of the “general” – and “takes on an uncompromisingly critical stance towards the existing state of affairs, and its institutions.”

Collision, constantly simmering antagonism, occasional open conflict between two perspectives and narratives deriving from different experiences, are impossible to avoid. It is impossible to prevent those conflicts from emerging, nor is it possible to stem the antagonism once it happens. The relationship between the management and the managed is antagonistic by nature: the two sides aspire to opposite outcomes and can only exist in a state of potential collision, in an atmosphere of mutual distrust, and under pressure from ever growing temptation to pick up a fight.

European Culture Congress – Wrocław

[8-11 September 2011]

ECC is a meeting of leading personas of the European culture – theoreticians and practitioners, intellectuals and artists. Its starting point is a book, written especially for the occasion of the Congress, by prof. Zygmunt Bauman and prof. Anna Zeidler-Janiszewska on the contemporary European culture condition and possible scenarios for its development. ECC will be one of the central events of the National Cultural Programme of Polish Presidency in the EU Council.

www.culturecongress.eu

“The conflict is especially glaring, clashes particularly bitter, and relations singularly fraught with catastrophic consequences, in the case of the fine arts – the foremost area of culture and the powerhouse of its dynamic...”

The fine arts are the most hyped up area of culture; for that reason they cannot resist undertaking ever new forays into new territory the taking up of guerilla warfare, through which to forge, pave and plot ever new pathways to be followed by the rest of human culture (“art is not a better, but an alternative way of being” – noted Josif Brodski “it is not an attempt to escape from reality, but the opposite: an attempt to breathe life into it”). Creators of art are by their very nature adversaries or competitors in activities, which managers would after all prefer to make into their own prerogatives.

The more they distance themselves from the existing order and the more staunchly they refuse giving in to it, the less suited are the arts and artists to the tasks placed before them by the administration; this in turn must mean, de facto or in spe, that their managers must regard them as useless, if not downright harmful to the enterprise. Managers and artists present one another with opposite aims: the spirit of management remains in a state of constant warfare with the casualness, which is the natural territory/ecoptype of art. But as we noted a moment ago, in their preoccupation with sketching-in imaginary alternatives to the state of things, the arts, whether they like it or not, rival the management whose control over human enterprise and effort expended in manipulating the likelihood of it taking place, come down in the last count, to its desire to dominate the future. There are therefore plenty of reasons why there should be no love lost between people of the arts and administrators...

Marriage of convenience

Speaking of culture, but bearing in mind predominantly the fine arts, Adorno acknowledges the inevitability of conflict between it and the administration. But he also claims that antagonists need one another; that, what is more, art needs champions, wealthy ones at that, since without their help, its vocation cannot be fulfilled. A situation not unlike that in many marriages where spouses are unable to live together in harmony, yet they cannot live apart either ... however uncomfortable, unpleasant, unbearable a life full of open clashes and argument may be, a life poisoned daily by a hidden mutual hostility, there is no greater misfortune that could befall culture (or more precisely the fine arts), than its complete and unconditional triumph over its opponent: “Culture suffers when it is planned and managed; yet when left to its own devices, everything cultural can become ineffectual, its very existence becomes questionable.”

European Culture Congress – Wrocław

[8-11 September 2011]

Discussion panels covering phenomena and problems of contemporary European culture will be accompanied by artistic projects entitled “Art for Social Change”. The artists and culture animators taking part in the event come not only from European Union countries, but also from the Eastern Partnership group: Ukraine, Belarus, Moldavia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Turkey and Russia.

www.culturecongress.eu

On expressing this view Adorno once again draws the doleful conclusion he reached with Max Horkheimer while working on “Dialectics of Enlightenment”: that history of old religions, as well as the experience of modern parties and revolutions, teach us that the price of survival is “transformation of the idea into currency”. This history lesson needs to be assiduously studied, says Adorno, in order to assimilate it and impress it upon the practices of professional artists, who carry the main burden of the ‘transgressive’ function of culture, and consciously accept responsibility for it, thereby making criticism and transgression into a way of life:

Appeals of creators of culture for the withdrawal from administrative procedures and for keeping a distance from them, sound hollow. If they were to listen to these claims, they would not only deprive themselves of their livelihood, but they would also lose all influence upon society and all contact with it – everything that culture cannot do without; this is something that even the most principled of arts dare not do.

What can one say: this is indeed a paradox and one of the hardest to solve at that .... managers must defend the order entrusted into their care as the “order of things”, that is to say the very system which artists loyal to their vocation, must tax, thereby exposing the perversity of its logic and questioning its wisdom. As Adorno suggests, administration’s innate suspiciousness towards the natural insubordination and unpredictability of art cannot but be a constant cassus belli for artists; on the other hand, as he does not fail to add, creators of culture cannot make do without administration, if, loyal to their vocation, and wishing to change the world (for the better if at all possible) they want to be heard and seen, and as far as is possible, heard out and noticed. Creators of culture have no choice, says Adorno: they must live with this paradox on a daily basis.

However loudly they may curse the contentions and interventions of the administration, the alternative to modus coviviendi is loss of meaning in society and immersion into non-being.

Creators may choose between more or less bearable forms and styles of management – but they have no choice between the acceptance and rejection of the institution of management as such. In any case, having the right to such a choice is an unrealistic dream.

Sibling rivalry

The paradox discussed here cannot be solved because, despite of all of the conflicts between them and tacit or noisy mud-slinging, cultural creators and officials co-habit the same household and participate in the same enterprise. Their disputes are a manifestation of what psychologists would describe as “sibling rivalry”. Both one and the other are governed by the same understanding of their role and its purpose in a shared world, which is to make that world different from what it would continue to be, or become without their intervention, and input into its condition and functioning. Both of them harbour a (not unfounded) doubt as to the ability of the existing, or desired order to sustain itself, or to come to be by its own powers and without their help. They do not disagree that the world needs constantly vigilant monitoring and frequent adjustment; the disagreement concerns the subject of adjustments and the direction the corrections should take. In the last count, the only stake in the argument and constant power struggle is the right to make decisions in the matter, and make one’s point stand, or decision binding.

Useless beauty

Hannah Arendt went a step further and looked beyond the direct stake in the conflict, reaching so to speak, to the existential roots of discord: “Things are subject of culture as long as they last; their permanence remains in opposition to their functionality – an aspect which would make it transient and cause it to disappear from the world of phenomena, by exhausting them, using them up or wearing them out... Culture finds itself under threat, when all objects, created now or in the past, are treated solely through the prism of functions played in vital social processes – as though they had no other right to exist beyond the satisfaction of some need, and this regardless of how noble or how base that need may be.”

European Culture Congress – Wrocław

[8-11 September 2011]

The programme of ECC combines theory with cultural practise. Such form makes it closer to a social-cultural festival, rather than an academic debate. The programme includes, among others, design, video and modern art presentations, which aim at showing culture as an instrument of social change and a foundation for creative society. It will also present music, theatre and film projects, art formats such as Emergency Room, Pecha Kutcha and an integration game for non-governmental organisations.

www.culturecongress.eu

According to Arendt, culture reaches beyond and above current realities. It is not concerned with what at a given point might be in the order of the day and might be hailed as “the imperative of the moment”; at least it strives not to be bound by limits defined by “actuality” of the matter, whoever may declare it as such and by whatever means they may do so, and to free itself from the constraints imposed by it.

To be utilized/consumed on the spot, moreover to be damaged in the course of use/consumption, is not, according to Arendt, the destiny of cultural products, nor is it the measure of their worth. Arendt claims that the point of culture (i.e. art) is beauty – I think she chooses to define the interests of culture in this way because the idea of beauty is a synonym, or an embodiment of an ideal which resolutely and stubbornly eludes rational justification or causal explanation; beauty is by its nature devoid of purpose or obvious use, it serves nothing but itself – nor can it justify its existence by invoking a recognized, palpable and documented need which impatiently and noisily demands to be satisfied.

Whatever needs art might eventually satisfy, they must first be conjured up and brought to life by the act of artistic creation. A thing is “a cultural object” if it lasts longer than whatever practical use might accompany or inspire its creation.

Changes are coming

Cultural creators may rebel today as they did in the past, against a meddling and intrusive intervention which insists on assessing cultural objects according to criteria of other creations, alien and ill-disposed to the natural non-functionality, unruly spontaneity and intractable independence of creation; they may rebel against bosses, both appointed and self appointed, who exploit, just as they did in the past, the powers and means at their disposal, to demand compliance to rules and standards of usefulness drawn up and defined by themselves; who, summa summarium, just as in the past, undercut the wings of artistic imagination and undermine the principles of artistic creation. And yet something has changed in the last few decades in the situation of art and of its creators: first, the nature of managers-administrators currently in charge of art or aspiring to the position; secondly, the means which they use to achieve it; third, the sense given by the new breed of managers to the notion of “functionality” and “usefulness” which they expect of art and with which they tempt it and/or demand from it.

translated by Lydia Bauman

This article is a part of the Zygmunt Bauman's book “Culture in Modern Liquid Times”. The sub-headings come from the editors of www.cultrecongress.eu