PIOTR CZERKAWSKI: Mother Teresa of Cats follows in the steps of Savior’s Square, another Polish film inspired by newspaper journalism. When did it occur to you that the article about two boys who killed their mother wasn’t just a description of a situation, but could serve as a base for a deeper metaphor?

PAWEŁ SALA: As soon as I had read it. If I remember correctly, the article ran in “Gazeta Wyborcza”. It was a very thorough, analytical piece, a detailed examination of the psyche of the main characters. Stylistically, it reminded me of the work of Hanna Krall, whom I greatly admire. It was, in a sense, rather minimalistic, and that’s precisely what I sought to achieve in the film. I made sure it wasn’t too talky. I didn’t want to make it too obvious to the audience, but I didn’t want to leave them stranded either. I wanted to provoke viewers to construct their own theories.

Why was that so important to you?

I didn’t want to give the audience any preconceptions. I find the impossibility of unambiguously determining the cause of the murder to be the most interesting part of the whole story. If someone claims that they can clearly explain such complicated problems, then they’re either superficial, or they’re taking on the role of a Sunday school teacher. That’s not an attitude I like. I don’t like people who make themselves out to be self-proclaimed authorities and act preachy and condescending instead of leaving room for discussion. In my film, I chose to take the route of following a person’s story in an attempt to understand them. It wasn’t my intent to provoke either rejection or affirmation. You can’t praise a criminal, all you can try to do is humanise him. My characters were not psychopaths. People like that are locked up in special facilities. Crime simply brings out the dark side in man. Every one of us has a dark side.

The out of sequence chronology of Mother Teresa is an important part of the film. As each scene takes us deeper into the past, we realise that the responsibility for the tragedy lies not just upon the sons, but upon the entire family. Was this unconventional form a trap set for the audience?

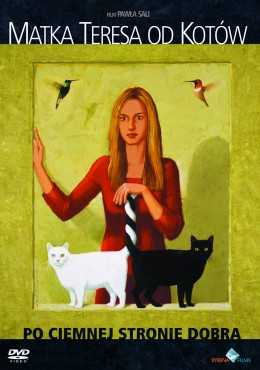

Mother Teresa of Cats: Sons

Mother Teresa of Cats: Sons

(Filip Garbacz and Mateusz Kościukiewicz).What it does is uncover how dangerously stereotypical our way of thinking is. When we see a murderer on television, we always think to ourselves that he must be deranged. But then a neighbour comes out and says that he was such a good boy and that he helped old ladies cross the street. That’s the greatest surprise. We find out that someone who had lived right next to us for all these years, someone who was polite, quite, and calm, all of the sudden does something that shocks us all.

Several years passed between the film’s inception and completion. You had trouble raising enough money. What is it about Mother Teresa that rubs people the wrong way?

Poland has cultivated an abundance of myths. We shield ourselves from reality with a handful of pompous slogans, and we go on pretending that the world is different from what we see outside our windows. My film uncovers the emptiness of that mindset, and I think many find that unpleasant. Of course, there’s a type of person that will never see the film. People brought up on morning TV shows would rather have the movie screen reflect what they see in their glossy magazines. They’re more interested in morning, evening, and afternoon hairstyles than they are in finding out where the evil in our everyday lives comes from.

You don’t believe that Polish viewers will be interested in seeing the film?

Mother Teresa of Cats:

Mother Teresa of Cats:

Mother (Ewa Skibińska). Quite the opposite, actually. I hope that many will go see my film if only because they’re sick of seeing cloying romantic comedies. Audiences are intelligent, it’s the decision makers who are incapable of assessing the needs of viewers and who try to convince us that some things won’t be understood or appreciated. Pre-premiere screenings showed us that, oddly enough, audiences at the Gdynia festival were least receptive. The crowds in Gdynia expect something more along the lines of a big event, rather that something that they’ll find moving. I warn every audience right before the film starts, explaining that I’ve made a sad, thought-provoking movie that doesn’t offer much in the way of entertainment.

The crime of matricide is a very rare one, but your film uses it as a kind of metaphor.

Murdering one’s parents or children, in the symbolic sense, is very common, for example when family ties are severed or when a child is kicked out of home. Events like this never make it onto the front pages of newspapers, but they are nevertheless painful. The “missing persons” section of a newspaper shows just how common an occurrence it really is. Those pages are full of ads taken out by parents begging their children to come home and telling them that they love them. But if that were true, then the kid would never have run away in the first place. Every family — just like the one in the movie — proves their own chaos theory. Minor misunderstandings, rejections, and stifled grievances are overlooked, but they build up inside and end up exploding at some point. Perhaps it’s because we, as a nation, aren’t very trusting of each other. We’re afraid of intimacy. It’s not just a Polish problem, it’s a problem in every postmodern society, where love and friendships have moved to the internet.

The title character is completely helpless in her relationships with other family members, and yet every day, her charm and communicativeness help her climb the corporate ladder. How does she reconcile these conflicting attitudes?

Every time Teresa leaves the house, she has to undergo a ritual metamorphosis into a nice, attractive insurance agent. She puts on a costume that lets her enact a certain social role. And she really is a dynamic, entrepreneurial woman, the only family member to have achieved some form of success. The problem is that her entire behaviour is based on a lie. Teresa’s tragedy is that she fails to recognise her problems. She considers herself to be a good mother, but that’s just her enacting yet another role. I wanted to use the title character to question our national belief in the mother as a holy figure, even by alluding to the Virgin Mary. Teresa’s motivations are very superficial and revolve largely around money.

Teresa’s husband Hubert is a disgrace to two very important archetypes in our culture. Not only is the man stripped of his authority as a father, he is also a defenseless, defeated soldier. What is it that makes him fail on both fronts?

Mother Teresa of Cats:

Mother Teresa of Cats:

Father (Mariusz Bonaszewski).The deterioration of Hubert’s family ties reflects a problem faced by an entire wave of people who emigrate in search of work. The character could just as well have left for London to wash dishes in a restaurant or gone strawberry picking in Spain. The military connection, however, enabled me to make a few more observations. I really wanted to avoid turning Hubert into a neurotic character whose wartime trauma leads him to abuse his wife and children, which is a popular motif in American films. My character returns to Poland convinced that he’s coming home from war. He suddenly realises that he’s stepped into another war — a civil war taking place in his own home, where everyone loses in the end. What is also relevant to our judgment of this character is the fact that Hubert, just like his fellow soldiers deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, symbolises the loss of innocence of the Polish serviceman. He is no longer a hero. It’s not freedom that he fights for — just like his wife, he fights for nothing more than a paycheck. We convince ourselves that we can control our wealth and fate in the long run. But capital is liquid, it flows from institution to institution, from country to country. No government can ever guarantee us prosperity or the sense of financial security, because capital will always move to wherever it can find better conditions for growth.

In the film, material wealth leads to spiritual poverty.

Paweł Sala

He was born in 1958. Playwright and director. Graduate of cultural studies at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań and faculty of radio and television at University of Silesia in Katowice. He is an author of documentary films, including Extras produced on the set of Roman Polański’s The Pianist. Mother Teresa of Cats is his feature debiut.

This is particularly apparent in the family’s relationship with Ewa, Teresa’s distant relative, who moves in with the family at one point. The girl is an artist and comes in with a certain sensibility that the others completely fail to perceive, because they belong to a whole other world. They don’t even realise that she could be an answer to their problems. They treat Ewa like a maid, like household help, nothing more. Teresa just mentions that she once had ambitions, too, but opted for a career instead. It’s actually quite characteristic — people have interests, they go to university, and then they end up as salespeople driving around in company cars.

Teresa’s emotional vacuum affects her sex life. Your film departs from the unrefined eroticism prevalent in Polish cinema. The two long sex scenes with Teresa and Hubert differ greatly in style, but they correspond very well with each other. Was is your intention to stress the changes that their relationship goes through?

Those scenes were very important to me. I tried very hard to find situations in which certain emotions could be conveyed without words. An opportunity to do just that came up in these scenes. The sex scenes required that I abandon, to a certain extent, any conservativeness and prudery. I made sure the scene at the custodian’s room, where Teresa uses sex to try to bribe Hubert into coming home, was ugly, awkward, and depressing. It had to be nothing more than physical release, without any semblance of emotional closeness. Meanwhile, in the earlier scene in the forest (chronologically speaking), the sex is a result of a spontaneous urge. It’s an expression of joy, and serves as a symbol of the couple’s wasted opportunity to salvage their marital bond.

Mother Teresa of Cats is certainly an ambiguous title, and can be analysed at several levels. What’s the story behind the title?

When I was first thinking about the title of the film, I wanted it to refer to Greek mythology, but the ideas I came up with seem awfully pretentious in hindsight. The problem was that I couldn’t come up with anything better for a long time. I happened to read an interview with Reni Jusis [Polish pop singer - ed.], who was asked the question: “Who is the most important person in your life?” She responded, “My mother, Teresa.” It immediately dawned on me how great that combination of words was, linguistically speaking. When you hear “mother”, you think “Teresa”. I later saw the reference to Mother Joan of the Angels, which led me to final version of the title.

The reference to the film by Jerzy Kawalerowicz has a deeper meaning. Is Teresa possessed?

In the story by Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz and in the film by Kawalerowicz, we are made to believe in a kind of possession that affects the sacred. Meanwhile, possession in my film affects only the profane. Instead of being possessed with lust, my characters are possessed with powerlessness, and instead of angels I have cats. Even if Teresa turns to the church in the face of danger, it remains closed to her. Our problems have gotten to a stage where I believe the solutions offered by religion are no longer of any help.

Teresa’s son Artur seems possessed as well. The boy tries to convince everyone around him that he knows black magic and has supernatural powers. What does he want to achieve by doing this?

Mother Teresa of Cats,

Mother Teresa of Cats,

dir. Paweł Sala, Poland 2010Artur’s actions are premeditated. He desperately struggles to improve his self-esteem. His behaviour ends up having the opposite effect. His mother feels threatened, not impressed, by the boy’s actions, and his father scorns him. He is left feeling even more shunned than before. The only person who appreciates him is his kid brother, Marcin. Their relationship is based on a kind of feedback loop. Marcin believes in his brother, but also demands that he constantly reaffirms his greatness. It was very important for me not to let the audience believe for a second that Artur had any paranormal abilities. He’s not a horror movie demon. He’s nothing more than an intelligent illusionist. Tragically, he believes in his own illusion and hopes his abilities will allow him to somehow exert control over others.

He sometimes tries to apply his supposed powers towards good. At one point in the film, Artur spontaneously offers to help relieve his exhausted mother’s pain. How does his subsequent failure affect him?

I consider that to be a key scene in the film. If Teresa had not been terrified of her son, who was just trying to transfer his energy to her, if she had just embraced him like a mother instead of fearing him, their fate would certainly have been different. Regardless, he is horrified by this intimate moment as soon as he realises how close he and his mother are. The two reject each other, echoing signs of an Oedipus complex. Artur is also fighting for the position of alpha male in the family. When Hubert comes home from his deployment, he discovers that his place has been taken by his firstborn son. The two clash with increasing ferocity. The father realises that unless he leaves, his conflict with Artur will continue to escalate and may lead to tragedy. He decides to move out. By avoiding one tragedy, he precipitates another. That’s why I consider Hubert to be the character who suffers the greatest loss in the film.

In one interview you stated that what we are witnessing in Poland can be described as “Catholic Socialist Realism”. I feel that the term is an apt description of one the greatest maladies plaguing Polish society. The place the party occupied in our minds has been taken over by the church, preventing us from developing the ability to think independently. Why is this such a big problem?

I think it might have something to do with Stockholm syndrome. We love to play the role of dependent victims. We build our greatness as a nation on the memory of our struggle for independence, on the myth that Poles will be no one’s serfs. But as soon as we won this independence, we began questioning it. Freedom is too great a challenge for us, because it requires us to take responsibility for our actions and choices. We think it’s safer to just have others do it for us. If you were to ask people on the street, they would certainly say they felt free. They fail to see that they think exactly as they are told to think, and live as they are told to live, that they’ve been subjected to brainwashing and fail to think independently.

translated by Arthur Barys