Following the recent exhibitions of the work of Wilhelm Sasnal (2007) and Luc Tuymans (2008), the Zachęta National Gallery presents yet another one of the art world’s “hot names”, Neo Rauch. The first of two rooms devoted to the show features pieces from the 1990s. Gloomy, subdued colours dominate the selection – dirty browns and shades of gray, industrial ochres, and tarry blacks – along with sharp contours directly inspired by blueprints and schematics. The atmosphere is reminiscent of post-industrial East Germany, a world of grand, failed dreams of building a brave new world of socialist construction projects, where tiny people wander around soulless, empty spaces tailored to an inhuman scale. The next room presents Rauch in his more colourful and spectacular incarnation: sweeping landscapes with sunsets lifted from kitschy wedding paintings, where figures painted in smooth strokes partake in undetermined activities: a man clad in a riding coat spears a mysterious creature in the rushes, resembling something between a plesiosaurus and a unicorn; a donkey-headed fellow unveils a bust atop a sculpting table, paying no heed to the man carrying a procession float; a fat jester gazes at a woman showing him a circle painted on a piece of cloth; two men wearing shining cuirasses over their work clothes stack cattle bones and horned skulls onto wheelbarrows. Here a curtain, there a candle, a handle, a drawing suspended from a string. A chaotic jumble of meanings, space, and compositions.

Neo Rauch. Ufer. 1993, private collection,

Neo Rauch. Ufer. 1993, private collection,

courtesy of Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig Berlin

and David Zwirner, New York,

photo Uwe WalterRauch obviously knows and makes use of the extensive history of art. But such banal ascertainments can apply to any practitioner of figurative painting, however insignificant. And not just figurative art – today, even video art has its respected predecessors, not to mention performance art and especially abstract painting. The objects of Rauch’s fascination are apparent as well: illustrations from East German alphabet books, user’s guides, and technical manuals; German Romantic paintings, from which Rauch has borrowed men in padded frock coats, shakos, top hats, and ascots; and even the Renaissance. If you want to find de Chirico in his work, you will; Łempicka and Balthus – them as well. Yet I find that hard to regard as an achievement in and of itself.

I am equally unimpressed by the astounding sums Rauch’s canvases fetch. The fact that Brad Pitt bought one of them for close to a million dollars is about as significant as Paris Hilton giving her dog 55USD bottles of water. Considering that the art market is ruled by intricate mechanisms and crazy antics, while its hierarchies are subject to turbulent reshuffling, the prices of canvases can hardly be considered a gauge of anything but the latest trend. Although I admit I (usually) prefer that such large sums end up being spent on art rather than luxury dog water with hand-applied Swarovski crystals, that’s still a far cry from actually appreciating the canvases.

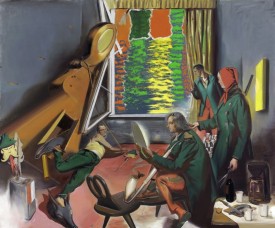

Neo Rauch. Unter Feuer. 2010.

Neo Rauch. Unter Feuer. 2010.

Museum der Bildenden Künste Leipzig,

courtesy of Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig

Berlin and David Zwirner, New York,

photo Uwe WalterOpinions recurring in the exhibition catalogue include statements along the lines of: “We will not be provided with the tools for unambiguous interpretation”, “The foundations of this art are delineated by opaque and mysterious […] combinations of people and props” (Joanna Kiliszek); “What could it mean that the man’s right hand ends in the bright yellow soundboard of a lute, and the left hand in a bag tied with a drawstring? Does that even mean anything?”, “People are tired of political correctness in art discourse. They want stories to once again be told in a manner that lets them lose themselves in their mysteriousness” (Matthias Flügge). These and other similar reviews of the exhibition show that Rauch’s art is hermetic, although I don’t know if it deserves to be described as “mysterious”. A mystery is something that refers us to something hidden and important, something we don’t know but sense or expect. A mystery is an invisible shape in the shadows. Yet with Rauch’s paintings, I do see a façade filled with enigmatic signs suggesting depth, crying “There’s something behind me!”, but I’m not sure if these words carry any value, if there really is anything behind the façade.

One comment by Rauch appears salient: “I’ll admit that the viewers I like most are the ones who perceive my canvases as paintings above all else, and pick up the narrative structure as need be, or – preferably – completely unconsciously. After all, that is precisely what I do when admiring a piece by Tintoretto or Beckmann.” What this proves is that he completely misses the point of the work of these two painters. Its undoubted formal qualities notwithstanding (extranarrative qualities, but nonetheless subject to the story and supporting it), Tintoretto and Beckman’s work was aimed at “readers” of paintings. An erudite Venetian strolling through the Doge’s Palace had no trouble picking out mythological references, subtle political allusions, and second or third layers of meaning; a simpler viewer, accustomed to seeing Tintoretto’s work at church, would be well acquainted with biblical stories and the lives of saints depicted on the canvases. Beckmann, on the other hand, was deeply involved in political causes, and his paintings – like those of Dix and Grosz – could almost be described as advocacy; they were rhetorical, and rhetoric is impossible without a mutual understanding, without negotiating a common channel of communication. Meanwhile Rauch, an artist described as “resurrecting allegory”, offers us little more than a hodge-podge of building blocks taken from other stories, fragments pulled at random from an enormous repository of images and juxtaposed in a spectacular form. My impression is that what is missing in Rauch’s work is what made the surrealists’ collages so powerful. Their art was the work of people steeped in 19th century culture and its myriad stories and languages. Their conscious centos were expressive, even if they were based on the subconscious. Magritte, Ernst, Delvaux, and Dali used scraps of the Great Stories as well, but they knew why they were putting them together the way they did, and more importantly, so did the viewers. Compared to surrealist collages, Rauch’s collages appear to be the parallel of the “Picassos” painted in the 60s and 70s – pieces that mimicked the formal measures while completely misunderstanding the art of Picasso. They copied the surface without grasping the essence.

Neo Rauch. Quecksilber. 2003,

Neo Rauch. Quecksilber. 2003,

private collection, courtesy of Galerie

EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and David Zwirner,

New York, photo Uwe WalterI have even greater doubts about the praise heaped on “the neoconservative Rauch’s” technical mastery and supposed anatomic dexterity. If we were to apply conservative terms to his art (where a painting is either “good”, meaning mimetic, or “bad”), we would say that the canvases are painted rather badly. Joanna Kiliszek’s claim that Quecksilber (which happens to be one of the best paintings at the show) resembles the work of Vermeer does Rauch more harm than good. It is immediately apparent that Quecksilber is about as far away from Woman Holding a Balance or The Lacemaker as Idaho is from Amsterdam. The only similarity I could find between the two artists is that Vermeer, as we know, used a camera obscura; most of Rauch’s late work gives the impression of having been made with the help of a projector (although I can’t be certain if that’s actually the case): a photorealistic face appears next to a carelessly painted hand that has all the clarity and anatomic fidelity of a bar of soap. It’s almost as if he had been copying an image that was cut off, forcing him to finish up without a crutch. The disproportionate, rubber-like appearance of the bodies gives an impression of ineptitude rather than a conscious measure on the part of the artist. I do not claim that anatomic fidelity and mimesis are the purpose of art; there are many outstanding works that are no better than kitsch in this regard. But if the artist is described as having “a solid background in anatomy, aesthetics, and metaphor” and “precise technique”, then I can’t help but shrug seeing how Rauch’s canvases are not even on par with most of the paintings presented at the memorable (and highly uneven) “New Old Masters” exhibition at the Abbot’s Palace in Oliwa, Gdańsk.

Rauch’s newer pieces, while certainly spectacular, have their admirers, just as the aforementioned “Picassos” did. To me, however, this Zachęta exhibition depicts a decline: from the interesting, unpretentious pieces of the 90s, in which frugal palettes and clarity of drawing and composition produced a gloomy, anti-utopian atmosphere, to the commercial canvases of the past decade, with their flashiness, sycophancy, and pretense of profundity.

Neo Rauch, “Begleiter. The Myth of Realism.” Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw, 12 March – 15 May, 2011. Curated by: Joanna Kiliszek.

translated by Arthur Barys