Edward Żebrowski hasn’t made a film in thirty years. A true shame, considering that the director’s career ended with his best film, In Broad Daylight (though he is co-credited, along with Krzysztof Zanussi, for writing the screenplay to The Unapproachablefor German TV). Żebrowski thus secured his position as a living legend and silent authority figure in the film world, although his movies can hardly be said to have achieved “cult status” with audiences. With Żebrowski’s work fading into obscurity, it is fortunate that Kino Polska has decided to release three the director’s feature-length films on DVD (although it’s a pity that the box set doesn’t also include his short films).

Żebrowski’s work is often thrust unceremoniously into the pigeonhole that is the “Cinema of Moral Anxiety” — understandably enough, considering it was he who founded the genre together with Zanussi. Żebrowski’s films are not so much about living people as they are about the stances they represent. It is these stances that engage in debate and conflict, but in a way that immediately reveals which of them is righteous and which is not. And if that were to exhaust the full scope of his films, they would now be respected but dead, at best. But there is something much more interesting and timeless about Żebrowski’s work: the conflict between discourse and the carnal. The drama of a body that forgets about its needs and responsibilities when subjected to an idea. The rivalry between biology and intelligence. Who emerges victorious? The answer, to some extent, may be found in Żebrowski’s forty-odd years of silence. It is no coincidence that all three of his films end in death.

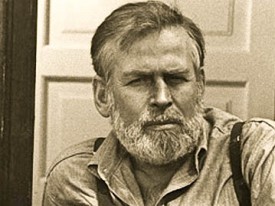

Edward ŻebrowskiThe protagonist of Salvation, Adam Małecki, is a biology professor, yet biology is precisely what he appears to lack. He is a strict, rational, unemotional, and principled person; a true construct of academic culture. He finds himself admitted to the hospital for some tests, which he fails to take seriously, believing that he will return to his lectures in a few days. But when the disease breeding in his body turns out to be more serious than he had believed, Professor Małecki has no choice but to remain in the hospital for several months of treatment, during which he faces the reality he had avoided for so long: the weakness of the body, its fluids, its reek, and its filth, but also the fears and (often false) hopes of other patients.

Edward ŻebrowskiThe protagonist of Salvation, Adam Małecki, is a biology professor, yet biology is precisely what he appears to lack. He is a strict, rational, unemotional, and principled person; a true construct of academic culture. He finds himself admitted to the hospital for some tests, which he fails to take seriously, believing that he will return to his lectures in a few days. But when the disease breeding in his body turns out to be more serious than he had believed, Professor Małecki has no choice but to remain in the hospital for several months of treatment, during which he faces the reality he had avoided for so long: the weakness of the body, its fluids, its reek, and its filth, but also the fears and (often false) hopes of other patients.

There is a stark contrast between the clothed and bare body in Żebrowski’s work. The former — preferably clad in a suit and tie, buttoned up to the top — appears to be his characters’ natural skin, perfectly fused with their gestures, manners, and reasoning. The naked body is a foreign, unnatural body. When it does appear, it is usually tortured, manhandled, and humiliated. Żebrowski’s second feature-length film also takes place in a medical institution. The titular Hospital of the Transfiguration is a clinic for the mentally ill. Doctors debate psychiatric theories over dinner, while patients are subjected to painful treatment, humiliating experiments, and outright abuse.

This cinematic adaptation of the novel by Stanisław Lem — one that the writer himself didn’t particularly care for — takes place in Poland shortly after the start of World War II. German forces soon arrive to get rid of all the “unneeded” sick bodies occupying the hospital. In the context of the impending annihilation, the doctors’ academic debates seem oddly out of place, exposing the powerlessness of reason in the face of physical violence.

As is common in Polish film, Żebrowski’s cinematic world is dominated by men. Women appear somewhere in the background, where they serve as assistants, aides, and messengers. With few speaking parts, they are enigmas that rarely trouble the minds of the male characters. The men have become entwined in a world of cold, hard ideas that produce not just research and discourse, but also intrigue, power struggles, and killing. The latter side of the male world is the one that ultimately gains the upper hand. This is true of both Hospital of the Transfiguration and In Broad Daylight, where a 20-year-old boy (one of Michał Bajor’s best roles) is assigned by an underground organisation to kill a famous writer (Jerzy Radziwiłowicz) accused of collaborating with the Russian secret police, only to discover that he himself has become the object of political machinations.

Another angle worth examining is the approach Żebrowski’s male characters have towards sex. Fenced off from the bodies of others by their suits, focused on science or ideology, they approach this area of life with great distrust (although it is they who are not to be trusted). In one particularly grotesque sex scene in Salvation, Małecki literally throws himself on his wife (played by Maja Komorowska), who stares off into the distance with an empty, agonising look in her eyes. The whole event is over after just a few spasms by the professor — spasms of desperation rather than lust. Meanwhile, in Hospital of the Transfiguration, the doctors seem completely devoid of any erotic needs, satisfied to practice medicine and spend time talking to other men. The sole character to display any appreciation for the senses is the cynical artist (Gustaw Holoubek), inspired by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, who takes morphine and has a romantic affair with a Jewish immigrant from Austria (Ewa Dałkowska). She and the film’s young protagonist, Dr. Stefan (Piotr Dejmek), share an intimate moment just before the hospital is overrun by Nazis, in what appears to be an attempt to find solace in each other rather than sexual intercourse.

The boldest love scenes are found in the film In Broad Daylight. The protagonist starts an affair with Ewa (Krystyna Janda), the wife of one of the organisation’s leaders. But their bodies are portrayed post coitum as they turn away from each other, as if becoming strangers. This can be interpreted as a warning, a foreshadowing of Ewa’s disloyalty to “Biały”.

The sexual dysfunction portrayed by the men in Salvation and Hospital of the Transfiguration is one more effect of their disconnection from their bodies — the very subject of their study. They wish to serve some greater order, be it intellectual, scientific, or patriotic in nature; to shed that which is mundane, lowly, unworthy of a man, especially a Pole. But in doing so, they make themselves all the more susceptible to disease, violence, and death — precisely what they wished to push out of their lives, or at least rationalise and control. To no avail. Żebrowski’s cinema is a cinema of defeat.

One of the final scenes of In Broad Daylight takes place in the sunny, sensual setting of Italy. The assassin enters the home of his mark, a writer suffering from tuberculosis. The man is napping in his garden. He notices the armed young man out of the corner of his eye. He doesn’t rise, he doesn’t panic, nor does he explain himself or beg for mercy. He merely asks the guest, “Are you from Poland?” His is a body that is bored with Polishness (and, by no mere coincidence, one that belongs to Radziwiłowicz, the man of marble and the man of iron). A body accused of treason, a body with no more strength to fight, but one that would very much like to fulfil its national duties, historical necessity, and moral anxiety. And, finally, achieve independence.

translated by Arthur Barys