“Today it seems as if the 70s never existed.” I recall reading in the late 90s a certain English article on Rainer Werner Fassbinder that opened with that quote. But I think the 90s never ended. Why would I mythologise them as if they were the 60s?

Personally, I should be nostalgic about the years following the fall of communism. Youth, university, my first relationships, my first sexual encounters, my first Warsaw Film Festival, my first published articles, my first trips to the West, etc. But the sentimental melody is interrupted by my acute awareness of the fact that those hopes, dreams, and promises were unfulfilled, or at most barely fulfilled. And I’m not thinking in personal terms any more — let’s put that aside. I’m talking about public affairs, which — I suppose — cannot be disassociated from personal happiness.

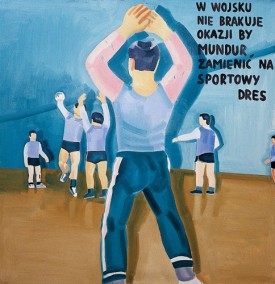

M. Maciejowski, There is plenty

M. Maciejowski, There is plenty

of chances in the army to swap

the uniform to sportswear,

courtesy of Raster GalleryThere is an excellent and underrated 1985 film directed by Fred Schepisi, based on the play Plenty by David Hare (the famous English playwright and screenwriter, author of The Hours). It starts as World War II is drawing to an end. Meryl Streep plays a courageous fighter in the French resistance, struggling for a brave, new world. One night, she has a short but passionate romance with a courier who parachutes into the forest on some important mission. The man must press on the next day, but the main character becomes convinced that this one night stand was a sign of a “better tomorrow”, one filled with similar passion and ecstasy. She goes on to cherish that night, thinking back upon it in times of difficulty.

The film goes on to tell the story of Susan’s life after the war. She marries a diplomat, enters powerful circles, and gets caught up in romantic affairs. Her life is marked with one disappointment after another. But in the broader context, the film also deals with the issue of disillusionment in post-war Europe: a divided, conformist, unjust, and hypocritical Europe. Years later, the character runs into her lover from the forest. They go to bed again, but both of have become dispirited, bitter alcoholics. The horn of plenty has left them with “just a string”. The final shots of the film take us back to the past. It is a beautiful, sunny morning, and someone arrives to announce that the war has ended. “There will be days and days and days like this”, Susan says.

I have retold the plot of Plenty in such great detail (from memory, and so I apologise for any omissions) because I too stood in a forest in the 90s. Like the character played by Meryl Streep, I though that since freedom had arrived and we were finally living in a democratic country, I could finally “cast off the coat of Konrad” [from a poem by Antoni Słonimski in relations to Adam Mickiewicz’s Konrad Wallenrod - ed.] (oh, how we reveled in repeating that quote in university!) and simply enjoy life. I was stupid, young, and naïve. I was too slow to realise that others did not want me to enjoy myself too much.

The 90s weren’t just a decade of crude, and often dirty, politics. It was also a time of extensive and brazen clericalisation. A time where power — both real and, more significantly, symbolic — was seized by mimeographed fathers, styrofoam heros, and their right-wing bastard children. It was a time when we discovered, our eyes wide with surprise, that the heroes of the underground opposition had, in many cases, turned out to be nothing more than imbeciles. To quote a prophetic hit by the band Perfect: “You, the prophets of my angry years, have grown fat.” It was a time of teachers who had confused ethics with egos, teachers who could do little more than admonish and exclude. A time of intellectual and artistic downfall (see: Polish cinema).

I realise that I might sound like one of the above-mentioned unwanted sons of Adam Michnik who have given themselves mental constipation from all that frustration and the trauma of rejection. But I am not of that litter. Frankly, I had hardly any interest in the Polish public sphere in the 90s. I was too excited about pirated cassettes with western music or my explorations of Paris and London. Cultural discipline was imposed with the passive complicity of people like myself, who later discovered themselves to be the victims. The guilt of not having done anything, not even speaking up, prevents me from enjoying my memories of the 90s. The edifice is just now beginning to crumble. Late. Too late.

I don’t enjoy going back to the Polish cinema of the period. I have instead discovered, many years after its release, the film Savage Nights by Cyril Collard, a movie that I have come to regard, for a variety of reasons, as the essence of its era. The 1992 picture is a largely autobiographical story about a bisexual HIV-positive man. The 35-year-old Collard (who also plays the lead role) died shortly after the premiere. He didn’t live long enough to win awards, reap glory, and witness the heated debates over his debut masterpiece. I saw Savage Nights at my first Warsaw Film Festival (the film ended up in standard release). Despite the morbid context, at the time the film struck me — with a certain exultation — as a breath of freedom, a taste of the relaxed social mores that would blow in from the Sienne.

Collard has been largely forgotten. He has not become a film legend, a French James Dean. Perhaps because his bisexual debauchery and his longing of pantheistic love were essentially narcissistic and onanistic. What is more, I now see that Savage Nights didn’t open anything up at all. Quite the opposite. Orgia e finita! It lasted throughout the 60s and 70s. The decadence of the 20th century fell upon the 80s, when the HIV virus was discovered, allowing Eros and Thanatos to embrace once again, bestowing a lofty and eschatological dimension on sexuality and surrounding it with new mythology. The normalisation process started in the 90s, with safer sex and safer investments. Cyril Collard, one of the last young AIDS gods, was gone forever. Savage capitalism may have been running wild in Catholic Poland, but we could only dream about savage nights. We slept with our hands on the covers, like good little boys.

The 90s were a decade of suckers, the price of which we are still paying today. A time that was largely lost. Do I feel like going back in search of lost time? I don’t think so.