A set of colour images taken in post-war Warsaw became a hit on Facebook in late October. A city in ruin became a city in colour. The appearance of colour in images once dominated by shades of gray had a strong cognitive effect. It wasn’t that the ruins “really” were in colour — it was that they could now be seen “anew”. The filter of familiarity was removed, enabling viewers to perceive (and even become fascinated with) the essence of the pictures: a record of destruction. The past suddenly seem contemporary, or at least stripped of the nostalgic patina of age.

The Archeology of Photography

Two albums published by the Archeology of Photography Foundation give a similar — albeit deeper and less dramatic — impression. Polesie, a collection of images by Zofia Chomętowska, and Kronikarki (The Chroniclers), with pictures of post-war Warsaw taken by Chomętowska and Maria Chrząszczowa, are the fruit of an enormous undertaking in terms of editorial and archival work. The albums are slick without being flashy, a point that photography lovers will appreciate. More importantly though, the books are the result of the consistent “archeology of photography” policy apparent in the foundation’s other titles, part of a broader tendency that I would describe as an attempt to reclaim photography.

The contemporary photograph is either transparent and used for its obvious illustrative function, or it is shrouded in a veil of nostalgia (“Look at the people back then — so beautiful, so beautifully dead.”) The success of photography — its mass popularity and ubiquity — has come to the detriment of its documentary value. On the one hand, the digital breakthrough sparked a heated debate on the essence of photography and inspired a flood of new books and albums devoted to the relevance of the medium as a form of documentation and as an art genre. On the other hand, it seems as if everything has already been photographed and that every event or association can be conveyed with a picture. In that sense, the photograph has become empty, obscuring reality rather than showing it.

Polesie and Kronikarki contain a number of well known and widely circulated pictures. The images presented in the former are often mentioned in discussions accompanying exhibitions and books on the inter-war period, while the latter come up in the context of World War II, and particularly the destruction of Warsaw. When used for this purpose, the images aren’t always associated with their authors. The photographs are used to illustrate a subject (such as the beauty and exotic character of the Polish and Polesie landscape) or support a thesis (such as the indictment of the German invaders). Yet the extensive collections of images contained in both albums are not limited to the “famous” photos. The illustrations are accompanied by thorough commentary explaining the context behind the images, while biographical essays about the authors offer insight in the meaning that the act of photography might have had for them.

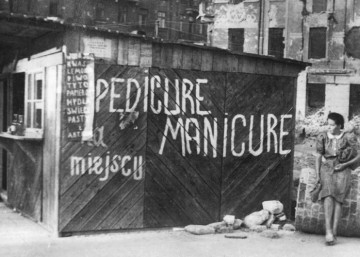

Maria Chrząszczowa, Plac Napoleona

Maria Chrząszczowa, Plac Napoleona

(Napoleon’s Square), 1945 – Kronikarki

Paradoxically, perhaps, for photography to regain its relevance as a method of documentation, for it to be stripped of stock meanings, habits, and interpretative clichés, and for its ambiguity and liveliness to then be made apparent, context must be inscribed into that diversity. This context is what makes it possible to save, or perhaps rediscover, photography. It forces us to finally look instead of knowing before looking.

The Ruins of Warsaw

The pictures of ruins taken by Chomętowska and Chrząszczowa illustrate this point well. The images were commissioned for the exhibition “Warszawa oskarża!” (“Warsaw Accuses!”), which was intended to show the cruelty of the Germans by depicting the destruction they inflicted on Poland’s tangible culture. In this aspect, the photos were part of the “ruin industry” that blossomed in Warsaw after the war; ruins were written about, drawn, and photographed. While the habit of documentation and the need for some form of therapy were behind this practice, the articles, exhibitions, and albums it produced played into the hands of propaganda. Powerful images were given preference over well-labeled but less emphatic pictures to make a statement. The broad and symbolic depiction of the ruins was a sufficient accusation, but it also served as a promise of the new order that was to arise from the rubble.

Zofia Chomętowska, Plac Trzech Krzyży (Three Crosses

Zofia Chomętowska, Plac Trzech Krzyży (Three Crosses

Square), 1945 – Kronikarki

Many of the photographs featured in Kronikarki can be interpreted as accusations, but there are also images depicting life in the ruins and portraits of the photographers themselves. In places the intention is purely aesthetic, involving a specific composition or juxtaposition of form. There is also meticulous commentary, compiled by Grzegorz Piątek, that places the photographed scenes in space and time, explaining what was located in a particular location before the war, and what was or wasn’t rebuilt afterward. This allows us to see both the (dead) ruins and the (living) city — not a symbol, but a chronicle, as the title of the album says.

A Woman with a Camera

An entirely separate — and fascinating — aspect revealed by the commentary in both albums is that of Zofia Chomętowska as a woman with a camera. Extraordinary as her life was, it reflected the characteristic tensions of the era. Chomętowska (née Drucka-Lubecka) was born in 1902 in Porochońsk, which belonged to the Russian Empire at the time, and died in Buenos Aires in 1991, when Polesie, the region of her childhood, was just being rediscovered as a Polish myth. She was an aristocrat forced by circumstance to provide for herself and her children. She was given he first camera, a small Kodak, when she was still a child. Her new hobby was at first treated with paternalism, like a childhood illness; years later, others would be surprised to discover that her photos had been taken “by a woman”.

She started out by taking pictures of familiar subjects: the Polesie landscape and people — themes that were exoticised in the discourse of the period. Her images were used for just such an illustration of the “beautiful frontier land”. Chomętowska eventually began traveling with her camera, taking photographs of picturesque Polish cities and resorts for the Ministry of Communication, or documenting parts of the capital that were not at all beautiful and needed to be improved, for Warsaw Mayor Stefan Starzyński.

The everyday practice of taking pictures, reinforced by her artistic background, produced in her a certain intuition for composition and a journalistic eye. The latter finds confirmation in the entries she wrote in her diary in September 1939 (published under the title Na wozie i pod wozem). In 1928 Chomętowska switched to a Leica, a 35 mm camera that wasn’t highly regarded in Poland’s photographic mainstream, dominated as it was by pictorialism and the later “homeland photography” project led by Jan Bułhak. This modern woman, who “carried a Leica and drove a Simca”, gladly took advantage of the capabilities offered by the small, handy, and fast camera, but for exhibitions and contests (in which she participated with great success), Chomętowska chose photographs that appeared to have been created with the use of different equipment. She accepted one more government commission after the war, and, likely sensing the direction the country was about to take, took advantage of her first opportunity to go to London with the “Warsaw Accuses!” exhibition, and never returned. She and her children settled in Argentina. Chomętowska never went back to photography.

Zofia Chomętowska in Porochońsk,

Zofia Chomętowska in Porochońsk,

family estate in Polesie, 1928

The cover of the album Polesie shows Chomętowska running. Based on her biography and photographs, one might in fact draw the conclusion that she spent her life on the run. This should not be confused with the modern-day fetish of “mobility”; Chomętowska was firmly rooted in a world of social and family ties, and a significant part of her experience came from living in particularly mobile times. As a photographer, she incessantly documented the world for her own pleasure, only later deciding what would be used in the official discourse, and in what manner. A discourse that demanded “beauty” or called for “accusation”. The symbolic meaning of Chomętowska final images are particularly relevant in this context. Her depiction of Warsaw in ruin shows life and destruction side by side. She extracted the dialectic of ruin as a symbol — both of civilisation and organic matter, of the end and a new beginning, creation and destruction — and broke through it, colonising the rubble with the everyday bustle of Varsovians.

She lived and made a living with her camera. This may reflect a sense of wholeness and completion, but also the tensions resulting from her constant negotiation of the different meanings and positions of photography: documents and symbols, records and rhetorical gestures, private documentation and public statement. Photography became a medium in the full sense of the word: an intermediary in her tense dialog with the world and a living tool through which she negotiated meaning and language.

translated by Arthur Barys