Strategy of Heteronym

Adam Mazur: What first inspired the concept for “Alias”?

Adam Broomberg: One year ago Karol Hordziej approached me and Olivier and asked: “Can you do one project for us?” We told him: “What if we invented a fictional artist?”. Next we thought that it would be much more interesting to create many fictional artists in the show. We started approaching artists with the idea. Some were very resistant. It was too much to abandon themselves, their politics, aesthetic strategies, their biographies.

Oliver Chanarin: Other artists responded in a quite different way. They saw it as an opportunity to be liberated from their daily practice. Suddenly they were given permission to take up ideas they would have never approach in usual circumstances. We were more interested in artists who were developing rich biographies for their aliases. Something more dangerous than just dressing up.

You connected literary fiction with photography. What was the criteria by which you made choice of an artist? Did text come first and then comes the photographer, or the other way around?

OC: There was no rule. Sometimes we did the match making of writers and artists. That was the case with Jennifer Higgie and Jeremy Deller. In other cases the artists knew each other and already had a history of working together, which they wanted to continue.

Łukasz Gorczyca and Łukasz Ronduda knew Janek Simon and decided to work with him.

Photomonth in Kraków 2011

The Month of Photography in Kraków is a photography festival that takes place every year in May since 2002. More than 30 individual and collective exhibitions go along workshops, seminars, lectures and film presentations.

ADAM BROOMBERG and OLIVER CHANARIN, curators of this year’s edition, are artists living and working in London. Their most recent book, People in trouble Pushed to the Ground is published by MACK. For more information, please visit: http://www.choppedliver.info/

AB: Yes, and David Goldblatt with Ivan Vladislavic.

Many artists decided to show their collages. How would you interpret this revival of this old-fashioned technique?

OC: It was interesting for us how many people used collage as an easy way to remove their authorship. We grouped some of these works together in the Grey Rooms.

You have commissioned works, and included all the results in the show?

AB: Yes, and quite often it was challenging for us.

OC: Not just that. We have been working with all the artists and writers along the way. There were many conversations, which have been just as rewarding as the outcomes.

Lee Cluderay, A Scottish Memory, 1929, collage

Lee Cluderay, A Scottish Memory, 1929, collage

AB: There is a difference between the Bunkier show and the commissioned works. The Bunkier show came out of our research. The more research we did, the more we realised that there is nothing new about the strategy of the heteronym and there were many artists making use of it. The question is why people keep on doing this.

OC: There were so many examples that this show could extend to another two floors and still be incomplete.

Art is more important then the police,

Art is more important then the police,

2008, collage

Editing an ExhibitionWas it the first time you worked as curators?

OC: Yes, but the experience is not dissimilar to editing a magazine, which we know by heart. We used to work as editors of Colors Magazine years ago. Curating an exhibition is a similar task in terms the whole process of commissioning, receiving, guiding, coordinating, getting things done in time.

AB: The difference is that with the magazine you receive the material and then you are able to edit it, while here we did not edit the material at all.

Adam Broomberg and Olivier Chanarin,

Adam Broomberg and Olivier Chanarin,

Chicago 4 from Chicago series, 2006

OC: No, I think we have done a lot of editing. A lot of interfering! Curators historically have had a more invisible role. Now, they are far more visible and use the work of artists to construct their own statements. We tried to do the opposite and to work closely with artists like an editor working with an author’s text. In this sense, we have done a lot of editing, positioning, rather than curating.

Your comparing curating to editing, not to being an artist, is surprising to me. How it is for an artist to become a curator?

OC: It’s impossible to make a sharp division between the exhibition and our practice as artists. If you go to see especially the Bunkier show and you read the texts you will discover a lot of our sense of humour and our particular way of telling stories. We are always performing different roles. Our book Fig. like the show at Bunkier, required us to many different functions – writer, photographer, editor, designer, curator. Perhaps we suffer from not sticking to one thing.

Artists remain anonymous here, while you are strongly present as artists, curators, or simply authors I would say. I’m sure it had to be problematic for artists.

AB: We had lots of debates about this. If it was possible for us, there would be no names including our own. Ironically our names are most visible of all. While other artists remain anonymous. The idea of the project is that we will not to reveal who is who.

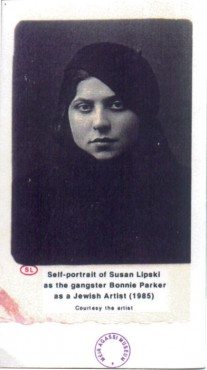

Meir Agassi, Self-portrait of

Meir Agassi, Self-portrait of

Susan Lipski as the gangster

Bonnie Parker as a Jewish ArtistOC: We do name all the contributing artists and writers. But we hold back the information about who did what. It’s a fundamental rule and one that we discussed as a group for a long time. The issue of authorship hovers over our own practice of course. That’s the reality of working as a duo – two brains, four arms. Perhaps when people work together it is harder to pinpoint the figure of the author.

AB: In a conversation between us and David Campany for Art Review magazine he asked an interesting final question : “Do the curators exist?” and our answer was: “They are fictional too.”

Yet you do reveal who’s who. All the names are disclosed at the end of the book. Once you find the names you immediately start to solve the riddle and see who is who.

AB: It is ok. We wanted to delay this moment as long as possible. If you go to many of the shows you are going to know immediately who is the author.

Was there any ghosts hanging above the show?

AB: Bad jokes.

OC: There is a danger with a theme like “Alias” of descending into a kind of spoof, in which everything is a poor fictional version of something else. Of course we wanted to avoid this.

Politics?“Alias” is a very beautiful and poetic story, but at the same time it raises a question concerning politics. Many of your previous works like for example “Chicago” were openly political. Is “Alias” political and – if yes – then in what way?

Maciej NowaczykAB: The artist, blogger Ahmed Sherif, made a piece called “Sank you”, under a fictional name. It was an anti-Mubarak propaganda piece that gathered thousands of followers on you tube. He was only able to reveal his true identity recently just after the revolution.

Maciej NowaczykAB: The artist, blogger Ahmed Sherif, made a piece called “Sank you”, under a fictional name. It was an anti-Mubarak propaganda piece that gathered thousands of followers on you tube. He was only able to reveal his true identity recently just after the revolution.

I am not talking about examples taken from the Bunkier show or from the commissioned pieces. What I mean is a more general impression concerning a framework in which these projects are presented. What would be political in this project apart from the authorship question that we have already discussed.

AB: First comes the subject matter. In many pieces politics are very present. There are works about Kabul, 9/11, the Japanese earthquake and Tsunami in Japan. The other thing is how artists become somehow involved in a literary, fictional world and how that raises questions concerning the relationship between the document and reality.

OC: The important reference for us is Roberto Bolano and his “Nazi Literature in the Americas”. It’s an anthology of right-wing authors, all of them invented by Bolano himself. Our first question was, why did Bolano need to employ this strategy? Was there something specific about the politics? One of our initial ideas was to present a festival of right-wing art. Once we started to research this, we realised that fiction as a strategy in art is used in many different ways, like in gender politics for example. So what you see in “Alias” is many complex ways of employing the strategy. It would be too simplistic to say it is only a political statement.

“Alias” is an attempt to redefine your own political agenda and explore potentiality of political fiction?

AB: A work presenting Black Saint in Kraków is explicitly political.

OC: I understand that you are saying it is much less evident and much less openly political than for instance “Chicago” which is absolutely militant, very clear, unambiguous. In its context “Alias” looks like a thing that is structured by lack of rigour, lack of patience. It shows that our definition of politics is changing. Perhaps also lack of formal art education is visible here and that all makes difficult to identify our work as openly political.

Parallel UniversesBecause of its richness “Alias” becomes a project about literally everything one can imagine. In this sense, it is very Borgesian. It presents stories of people living in separate complex universes…

In which you are always lost…

It is very solipsistic. Perhaps, this is why the exhibition at Bunkier Sztuki is so important, because it establishes a kind of a common ground, public space for discussion. It also strongly contextualises commissioned works. How is the exhibition narrated – it is not in chronological order, but is it divided into theatrical chapters?

OC: When we started accumulating a list of works for the Bunkier we saw immediately that we would never have the budget to transport them.

AB: For a budget of this show we could perhaps bring just one single work.

OC: No chance that we would get, for example, Marcel Duchamp to Bunkier Sztuki. So we had to somehow circumnavigate this limitation. And our solution was to re-represent the works… to appropriate it. We thought: “Let’s elevate the status of the installation photograph to a work in itself”. We went to meet some of the installation photographers at Tate Britain. They have their own language and terminology, it’s fascinating. For example an “official view” is a term given to a photograph of a piece of art that has been officially approved as a correct representation of a work of art by the artists or their estate. So this became a sort of sub-theme, and resonated with the fact that we were curating a “photography” festival of course. We kind of fell in love with this strategy and actually if we’d had an unlimited budget we would probably have ended up doing the same thing.

It reminds me of the general idea of appropriation art and institutional critique of Louis Lawler in particular… But there are exceptions to the rule of having only copies and reproductions in the exhibition: Die Antwoord and Roger Ballen or Zbigniew Libera…

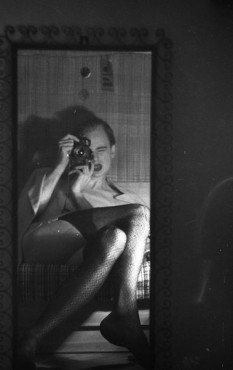

Zbigniew Libera, TransvestiteOC: Libera has been zoomed by us and then printed.

Zbigniew Libera, TransvestiteOC: Libera has been zoomed by us and then printed.

AB: Roger Ballen’s work here is not about Ballen’s psyche, it is about Die Antwoord. Ballen was asked to take photographs of the band. They always appreciated his work and here we can see how they appropriated his motifs to create a fictional persona. In this case they took a documentary, Ballen’s photographs, and appropriated them.

OC: We did not want our conceptual frame to inhibit the richness of the exhibition, so at certain moments we decided to break our own rules.

What about Blinky Palermo and Salvador Dali?

OC: Blinky and Dali – these are meditations on the power of names, which own lives of their own. It’s like a logo, a branding.

AB: During the last 20 years in England there has been more and more curatorial studies courses. It is not a calling anymore, it is now a profession. So what is happening is that curator is becoming more and more powerful. Becoming celebrities. More powerful than artists. In fact artists work become letters in the alphabet there for the curator to use in constructing a sentence – I need “the” and Walid Raad is always “the”, so I need him, like a preposition. That way he is put in all the shows. What would happened if Walid Raad would start to make something different?

OC: We want to resist the typical engagement with an art work, in which we first read the wall text and then look at the art!

It explains why this tiny booklet accompanying the Bunkier Sztuki show is so hard to navigate. Instead of helping audience to find a right caption it makes the whole story even more complicated.

OC: Like you said, very astutely, the order is not chronological or alphabetical. It’s governed by emotions, aesthetics, a sense of balance, or unbalance. It seems naive perhaps but I think stories and narrative govern much of the way we pieced this puzzle together.

Only when leaving Kraków I started to read a catalogue for the show. It turned out that it is a very interesting book in itself resembling a collection of surrealistic short novels or a bizarre set of experiments by some OULIPO members. Do you consider “Alias” also a literary piece?

OC: Yes, for sure. If you read for example the text by Lynne Tillman you can see that some of these texts are really exceptional. But that’s not quite the point actually. I remember when we approached Maria Fusco (who is the director of Art Writing at Goldsmiths University in London) she took offence at the way we were treating writers and artists as somehow distinct. For her there is no separation. And in some cases these roles did blur. It was also interesting talking to Jennifer Higgie who was one of the writers we commissioned and is an editor at Frieze magazine. For her the relationship between words and visual art was kind of turned on its head. Normally a work will be written about. But in the case of “Alias” the work is literally written into being. It creates all sorts of new challenges.

The Bruce High Quality Foundation

The Bruce High Quality Foundation