There is probably no other word that is as overused in media discourse as “generation”. I once tried to count the “generations” that have been proclaimed in the past ten years, since the well-known article about the so-called “Generation Nothing” (by Jakub Wandachowicz in the daily Gazeta Wyborcza, 2002 – ed.); I believe there were as many as twelve. They all had one thing in common: they only existed on paper. Reality never provided us with a single tangible, meaningful, unforgettable impulse, the common experience of which would forever distinguish us from previous generations. We were looking for it, but instead the groundbreaking change came unnoticed, along with cable TV, mobile phones, and, most importantly, internet access. It is only today that we can fully comprehend how much has changed over the past fifteen years.

We, the web kids; we, who have grown up with the internet and on the internet, are a generation who meet the criteria for the term in a somewhat subversive way. We did not experience an impulse from reality, but rather a metamorphosis of reality itself. What unites us is not a common, limited cultural context, but the belief that the context is self-defined and a product of free choice.

The manifesto

This manifesto was originally published in Dziennik Bałtycki (a daily newspaper) on 11 February 2012 under a BY-SA 3.0 Creative Commons license. In the following days, it was published in German by Die Zeit, in Spanish by the Spanish Pirate Party, in English on Cory Doctorow`s blog, The Atlantic Monthly and falkvinge.net, in French on framablog.org, in Estonian on Peeter P. Mõtsküli`s blog, and also in Czech and Swedish.

The manifesto is a part of a discussion on the ratification of ACTA in Poland, where thousands took to the streets to protest the proposed law.

As I write this, I am aware that I am abusing the pronoun “we”, as our “we” is fluctuating, discontinuous, blurred, and, according to old categories, temporary. When I say “we”, it means “many of us” or “some of us”. When I say “we are”, it means “we often are”. I say “we” only so as to be able to talk about us at all.

1.

We grew up with the internet and on the internet. This is what makes us different; this is what makes the crucial, although surprising from your point of view, difference: we do not “surf” and the internet is not a “place” or “virtual space” to us. The internet, to us, is not something external to reality but a part of it: an invisible yet constantly present layer intertwined with our physical environment. We do not use the internet, we live on the internet and along with it. If we were to tell our bildnungsroman to you, the analogue, we could say there was a natural internet aspect to every single experience that has shaped us. We made friends and enemies online, we prepared crib sheets for tests online, we planned parties and study sessions online, and we fell in love and broke up online. The web, to us, is not a piece technology that we had to learn and we managed to get a grip on. The web is a process, happening continuously and continuously transforming before our eyes; with us and through us. Technologies appear and then dissolve in the peripheries, websites are built, they bloom and then pass away, but the web lives on, because we are the web; we, communicating with one another in a way that comes naturally to us, more intense and more efficient than ever before in the history of mankind.

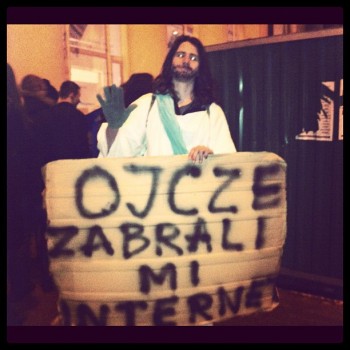

Brought up on the web, we think differently. To us, the ability to find information is as basic as the ability to find a railway station or a post office in an unknown city is to you. When we want to know something – the first symptoms of chickenpox, the reasons behind the sinking of the “Estonia”, or whether we’ve been overcharged on our water bills – we take measures with the certainty of a driver in a GPS-equipped car. We know that we are going to find the information we need in a lot of places, we know how to get to those places, and we know how to assess their credibility. We have learned to accept that instead of one answer we find many different ones, and out of these we can abstract the most likely version, disregarding the ones which do not seem credible. We select, we filter, we remember, and we are ready to swap the information we’ve acquired for new, better data, when it comes along. Father, they took away my internet,

Father, they took away my internet,

photo: Alexey Sidorenko (sidorenko_alexey_a), flickr,

CC BY-NC 2.0 licenseTo us, the web is a sort of shared external memory. We do not have to remember unnecessary details: dates, sums, formulas, clauses, street names, or detailed definitions. It is enough for us to have an abstract, the essence that is needed to process the information and relate it to other data. Should we need the details, we can look them up within seconds. Similarly, we do not have to be experts in everything, because we know where to find people who specialise in what we ourselves do not know, and whom we can trust. People who will share their expertise with us not for profit, but because of our shared belief that information exists in motion, that it wants to be free, that we all benefit from the exchange of information. Every day: studying, working, solving everyday issues, pursuing interests. We know how to compete and we like to do it, but our competition, our desire to be different, is built on knowledge, on the ability to interpret and process information, and not on monopolising it.

2.

Participating in cultural life is not something out of the ordinary to us: global culture is the fundamental building block of our identity, more important for defining ourselves than traditions, historical narratives, social status, ancestry, or even the language that we use. From the ocean of cultural events we pick the ones that suit us best; we interact with them, we review them, and we post our reviews to websites created for that purpose, websites that also recommend other albums, films or games that we might like. There are films, TV shows, and videos that we enjoy with colleagues and friends from across the globe, but our appreciation for other content might only be shared by a handful of people that we will never meet face to face. This is why we feel that culture is becoming simultaneously global and individual. This is why we need free access to it.

Warsaw protests, photo: Alexey Sidorenko

Warsaw protests, photo: Alexey Sidorenko

(sidorenko_alexey_a), flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0 licenseThis does not mean that we demand that all products of culture be available to us free of charge, although when we create something, we usually just release it back into the internet. We understand that, despite the growing availability of professional-quality audio and video technology, creativity requires effort and investment. We are prepared to pay, but it is obvious to us that the giant commission demanded by distributors is grossly overinflated. Why should we pay for the distribution of information that can be easily and perfectly copied without any loss of the original quality? If we are getting nothing but the bare information, we want the price to be proportionally lower. We are willing to pay more, but then we expect to receive some added value: interesting packaging, a gadget, higher quality, the option of watching it here and now, without waiting for the file to download. We are capable of showing appreciation and we do want to reward the artist (since money stopped being paper notes and became a string of numbers on the screen, paying has become a somewhat symbolic act of exchange that is supposed to benefit both parties), but the sales goals of corporations are of no interest to us whatsoever. It is not our fault that their business is no longer viable in its traditional form, and that instead of accepting the challenge and trying to reach us with something more than we can get for free, they have decided to defend their obsolete ways.

One more thing: we do not want to pay for our memories. The films that remind us of our childhood, the music that accompanied us ten years ago: in the external memory network, these are simply memories. Remembering them, exchanging them, and developing them is to us something as natural as the memory of “Casablanca” is to you. We find online the films that we watched as children and we show them to our children, just as you told us the stories of Little Red Riding Hood and Goldilocks. Can you imagine being accused of breaking the law for doing so? Neither can we.

3.

We are used to our bills being paid automatically, provided we have sufficient funds in our accounts; we know that starting a bank account or switching mobile phone carriers is just a question of filling in a single online form and signing an agreement delivered by a courier; that even a trip to the opposite corner of Europe with a brief sightseeing detour in a city along the way can be organised in a mere two hours. Consequently, as the users of the state, we are increasingly annoyed by its archaic interface. We do not understand why filing our taxes requires that we fill out several forms, of which the main one contains no less than one hundred questions. We do not understand why we are required to formally file a change of permanent address, as if city councils couldn’t sort it out amongst themselves without our intervention (not to mention the sheer absurdity of having an official permanent address). Down with the muzzles, photo: Alexey Sidorenko

Down with the muzzles, photo: Alexey Sidorenko

(sidorenko_alexey_a), flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0 licenseThere is not a trace in us of that humble acceptance displayed by our parents, who were convinced that administrative issues were of utmost importance and who considered interaction with the state as something to be celebrated. We do not feel that respect, rooted in the distance between the lonely citizen and the ebony towers of the ruling class, barely visible through the clouds. Our view of the social structure is different from yours: society is a network, not a hierarchy. We are used to being able to start a dialogue with anyone, be it a professor or a pop star, and we do not need any special qualifications related to social status. The success of the interaction depends solely on whether the content of our message is regarded as important and worthy of reply. And if, thanks to cooperation, continuous dispute, and defending our arguments against critique, we have a feeling that our opinions on many matters are simply better, why would we not expect a serious dialogue with the government?

We do not feel a religious respect for “institutions of democracy” in their current form; we do not believe in their axiomatic role, as do those who see “institutions of democracy” as a monument in and of themselves. We do not need monuments. We need a system that will live up to our expectations, a system that is transparent and efficient. And we have learned that change is possible: that every uncomfortable system can be replaced and is replaced by a new one, one that is more efficient, better suited to our needs, and offers more opportunities.

What we value most is freedom: freedom of speech, freedom of access to information and to culture. We feel that it is thanks to freedom that the web is what it is, and that it is our duty to protect that freedom. We owe that to future generations, just as much as we owe it to them to protect the environment.

Perhaps we have not yet given it a name, perhaps we are not yet fully aware of it, but I guess what we want is real, genuine democracy. A kind of democracy that goes far beyond the wildest dreams of your newspaper columnists.

translated by Marta Szreder

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Uznanie autorstwa-Na tych samych warunkach 3.0 Unported License.