Aptly described as “ostensible” in its very title, this play is a “biography” that only pretends to be one. This earnest warning is also an insurance policy, however. There is another character besides Maria Komornicka/Piotr Włast in the piece, one who makes regular appearances in the narrative, not unlike Nabokov in his own novels. And, like the voice of the narrator in a Godard film, this figure keeps the audience from settling into the illusion. His presence is a decisive factor in this “biography”: it is he who turns it into make believe, into openly theatrified fiction: fiction squared, or an exercise in meta-narration.

Maria Komornicka

Born 1842 in , died 1910. Polish poet, translator, literary critic, teacher. In 1862 she married a poet Jan Lemański, whom she dicorced in 1977. Since she was 31 years old she only wore male clothing, and functioned under the pseudonym of Piotr “Weirdo” Włast. Some sources claim that Komornicka extracted all her teeth, so that her face looked more masculine.

This other figure is someone who attempts to recreate the life and thoughts of Polish modernist literature’s most famous “misfit” by reading his/her writing and what has been written about him/her. He is someone who is distrustful of libraries and bibliographers, and so he sets off for Grabów, the location of the Komornicki family estate (from which he returns disappointed, not having felt the genius loci). He is someone who, in the very first words of the play, reveals his interest in “alternative stories and missed opportunities, rather than concise form”, which is why, having read an encyclopedic summary of the writer’s life story – the inscription on her statue in Grabów – he “began to imagine other, nonexistent monuments to Maria”. According to the script, this other character is called the Sculptor.

The Maria we see in the performance is therefore an obviously made-up character, or rather a series of characters: a sequence of sketches, none of which aspire to be the single, true image. It is a completely mediated image: its form is shaped by the one who follows and sketches it – the Sculptor. Not only does this stalker impose his own conditions on the narrative, but by selecting which events in the character’s life to reveal and which to omit, he also controls the meaning. He remains in the shadows, and yet he retains full control. Maria is helpless against his power. She is whatever he wants her to be.

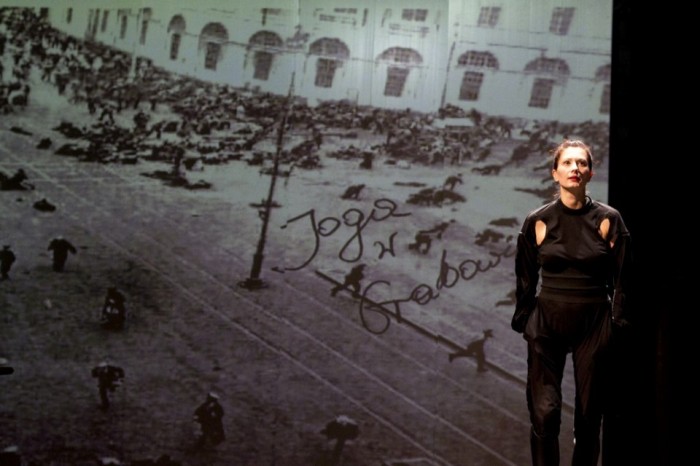

By introducing the stalker/author of a reinvented biography into the script, Bartek Frąckowiak and Weronika Szczawińska self-ironically comment on their own prerogatives as well as the gender context in which Maria Komornicka is usually placed as an author. This time, the pieces of her biography are put together by a man: a self-proclaimed, rather insolent biographer. He gets away with more. Instead of dwelling on Maria’s relationship with her mother (as Izabela Filipiak does in her excellent monograph Obszary odmienności), he analyses the traumatic bond between her and her father. Instead of her book Forpoczty, he talks about weasels, attics, mental institutions, and her travels in Europe. Instead of focusing on how she nobly stood up for her Jewish friends against insinuations leveled by other Polish writers, he reveals – spitefully and with obvious pleasure – virulently anti-semitic excerpts from her letters. He is equally ruthless about Maria’s lack of political sensibility, her apathy in the face of the evil flooding Europe and the immediate surroundings of the Komornicki estate in Grabów, while she (now as Piotr) practices yoga in an act of escapism. Maria’s transformation into Piotr, an absolutely crucial event to all her biographers and critics, is nonchalantly and provocatively omitted in the Sculptor’s version of the story (“He felt no mystery, no madness, no threshold or breakthrough.”), seriously violating the consensus on Maria and her gender that has reigned among feminists ever since Maria Janion published her first essays on Komornicka thirty years ago.

Komornicka. The Ostensible Biography

First staged 24 February 2012 on InVitro Stage of Culture Centre in Lublin, and 9 march 2012 in Teatr Polski in Bydgoszcz.

Director: Bartek Frąckowiak

Playwright: Weronika Szczawińska

Maria Komornicka performed by Anita Sokołowska

In order to liberate Maria from any appropriating discourse, even the most noble and righteous, Frąckowiak and Szczawińska attempt to strip her character of heroic masks (cleverly employing the Sculptor to this end): the “holy martyr”, an icon of the struggle for “third gender” rights, a patron of transgression who dared question the status quo, and paid the terrible price of exclusion – thus expanding our own freedom. They attempt to defuse these myths in order to rehabilitate individual experience and so that the biography may regain its rightful proportions. Their Komornicka can’t be a permanent monument. In that case, who is she supposed to be?

“Exiled from culture”, she returns as a conscious madman, or a jester who questions the gravity of all possible narratives, even those about himself. This return takes place in an exhibition space (designed thoughtfully and with restraint by Anna Maria Kaczmarska). Komornicka appears surrounded by shreds of her own biography, selected according to some non-canonical concept and displayed in showcases placed on pedestals and hung on walls. Shoe-shapers, a handful of teeth, a glass head filled with nuts, anatomical sketches, a two-headed doll and a reproduction of Bellmer’s famous Dolls. Maria/Piotr is intended to be something of a guide to all of this cryptic visual commentary on her biography; an ironic, hyperconscious subject that cannot be enclosed in a showcase. And this is where the trouble starts. She instead becomes yet another exhibit. An animate one, yes, but nevertheless an exhibit. A speaking, moving doll. A prisoner of form.

No longer a cunning jester who specialises in ridiculing authority and desecrating the status quo, Frąckowiak’s Komornicka (the Sculptor is now just the director) turns into a circus clown, a master of effects and a purveyor of entertainment. But in this case, the next part – laughter checked by its unceremonious disruption of the sense of order, leaving all questions unanswered – never comes. The circus performance is limited to play, display, and showmanship.

Anita Sokołowska’s task, on the other hand, is to show us what she’s capable of as an actor. To borrow a term from Motokiyo Zeami, she is an actress/squirrel: agile, lively, eagerly releasing mad bursts of energy, generously putting all her cards on the table – there’s no ace left up her sleeve. Can she play the saw? Sing like Nina Hagen? Leap onto a vaulting buck? Pretend that she can’t do it after all? Split phrases into micro-meanings? Shout them out, whisper them, chant them? Hit a high, emotional C and then wink at the audience? Be a man? A woman? Neither one nor the other? Both one and the other? Why, certainly!

The genre of the monodrama is ruthless: the lone actor must seduce the audience by all available means. The skomorokh – one version of the ancient clown figure, shown beating a drum, reciting poetry, and performing somersaults and crude gestures in Andrey Rublyev – has no other way to capture the spectators’ attention (and encourage donations). His art involves the combination of skilled craft and the readiness to improvise – essentially, the acceptance of the unexpected. Frąckowiak directs the actress/skomorokh in a way that relies exclusively on the former.

The Sculptor/director is a perfectionist. He creates a tight, rhythmic, and mathematically precise score, to which he subordinates all other parts of the performance, assisted by the vigilant onstage presence of a musician (Krzysztof Kaliski) – or perhaps even more so, by a metronome. In an attempt to save the character from unambiguity, he pushes the actress into the trap of restricted form (constantly emphasising that it is nothing but form), which simulates the multitude of meanings that are there to be discovered. The display draws attention to itself above all else.

Komornicka/Włast disappears between circus tricks. That was probably the intention. The disappearance of the character can be proclaimed a victory of metanarration over narration and the ostensible over the real biography. It also teaches us that even the most subtly implemented biographical project is doomed do failure, and also that culture (text, exhibition, play) is always more powerful than biography.

And what about the Sculptor? “Maria erased herself before he even saw her.” Despite the above reservations, one cannot but appreciate the honesty of that statement.

translated by Arthur Barys