Paweł Łoziński (born in 1965), a son of the esteemed documentary film director Marcel Łoziński, assisted Krzysztof Kieślowski on the set of Trzy kolory: Biały (Three Colours: White). Later, when making a documentary film celebrating the centenary of cinema, commissioned by the British Film Institute, he also executed Kieślowski’s concept. Beginning a filming career in the shadow of the old masters could have been burdensome, but time has proved otherwise.

Polish School of Documentary,

Polish School of Documentary,

Paweł Łoziński DVD

(The National Audiovisual Institute, 2009)His father did not try to talk him into studying film. “On the contrary”, says Paweł Łoziński, “and maybe that had more of an effect on me than if he’d tried to persuade me. When I finished high school I couldn’t decide what I wanted to do for a long time. I gave up the idea of studying maths and found manual work - first, as a film set carpenter, then as a grocery shop assistant. I painted a subway, built a house in Pyry and did electric maintenance work at the Central Office of Weights and Measures. Finally, I became weary of that and thought that perhaps there was something I wanted to say through film. I thought I’d give it a go and see if it was really so hard. Father helped me a lot. But that sort of help can be overbearing. I had to redefine our relations and rebel at some point. Today, I’m his critic - and he is mine.” In his famous debut Miejsce urodzenia (Birthplace) (1992), which was awarded a Grand Prix in San Francisco and Marseille, Paweł Łoziński found his own path and showed his temperament as a documentary film maker. At the same time he remained a continuator of the Polish documentary tradition. Perhaps the greatest one?

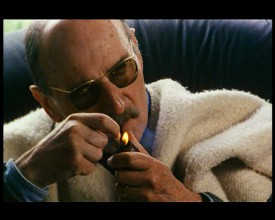

Still from Sławomir Mrożek przedstawia

Still from Sławomir Mrożek przedstawia

(Sławomir Mrożek presents) (1997)In the era of globalisation, documentary films are made on an ever grander scale. They surpass one another in being eye-catching, spectacular and based on increasingly elaborate formal concepts. Both, clandestine and overt staging is employed, and cameras sneak behind the curtain of world politics and economy as well as private lives of celebrities. World mysteries are penetrated and exposed courtesy of assorted TV channels. Paradoxically, while bringing the world closer to us the media isolate us from it, portraying it as great fiction and turning the viewer into a consumer of images. We appear to be living next to each other in increasingly isolated worlds and ever more stratified societies. In view of all that, the ordinary reality – the lives of our neighbours and the dramas next door – is becoming a “world not depicted”, a world which is as exotic as in the early days of Kieślowski and Łoziński, whose realism of the 70s was revolutionary and “iconoclastic”, and a protest against the official media. Their films were aimed at building social solidarity. Today – in a different political system – cinema is still intended to build bridges between people, though it is unlikely to play an equally important social role. It is vital to rebuild the trust of a viewer immersed in a world of fiction and used to being humoured with cheap thrills and close-ended narration formats.

Paweł Łoziński comments on the Polish school of documentary tradition, “I try to take a close look at the world which is seemingly unattractive. After all, what can be attractive about people being confined to their beds and undergoing chemotherapy? But to me, that’s interesting. I don’t look for outward attractiveness. I look for things which are completely ordinary, yet which people can identify with and see themselves in.”

Still from Sławomir Mrożek przedstawia

Still from Sławomir Mrożek przedstawia

[Sławomir Mrożek presents] (1997)Such situations are rarely noticed by the media which bow to sensationalism and go after drastic themes that are more marketable. One should stop, however, and allow reality to play its drama before one’s eyes. This requires a special gift – an ability to combine sensitivity with discipline, and empathy with distance. Paweł Łoziński is adept at doing both.

His curiosity about ordinary people and the world in earshot is something Łoziński shares with the old masters. But there is an element which differentiates his films from the films of his father and Kieślowski. The two men would first set a premise and a structural concept which would lead to a metaphor. In his older films Marcel Łoziński contrived interpersonal relations and situations, and employed psychodrama. He observed people within the framework of a certain system. If he ever came close to his objects, it was via special envoys who provoked them, such as in Wszystko się może przytrafić (Anything Can Happen), where his son Tomek (Paweł’s stepbrother who featured in his 100 lat w kinie [100 Years at the Cinema]) approaches strangers in a park.

Paweł Łoziński tries to follow reality. As in his father’s films, there is grudge, mistrust towards human nature and a sense of injustice in the world, but there is also greater acceptance of reality. He is intuitive and has ease in coming close to people and inducing them open up to him. When making a film he has no compelling desire to know where the material will take him.

Regardless of the theme, Łoziński’s films contain exceptional psychological portraits - human types as if borrowed from literary classics. Even Sławomir Mrożek, who features in one of his documentaries, and who tries to elude the director, unfolds before him like a character from a Chekhov’s drama. Caught at the moment when he is leaving Mexico for Poland, he tells a story of his many getaways and liberations: from his parents, the state, success and, finally, from himself.

Łoziński made Taka historia (The Way It Is) (1999), Siostry (Sisters) (1999) and Pani z Ukrainy (A Woman From Ukraine) (2002), featured in this album, single-handedly with his personal camera in the courtyard outside his home and even in his own flat. He was alone with his characters - his neighbours in the Warsaw district of Powiśle: the caretaker, the retired hairdresser, the two elderly ladies, as well as the Ukrainian gastarbeiter who came to his flat to clean and cook. Owing to his unobtrusive presence, the audience gets the impression that they are alone with the characters, and share in their loneliness. The act of filming serves as a means of breaking the loneliness, which appears to be the dominant theme in Łoziński’s most recent films, such as Chemia (Chemistry) (2008), filmed in a cancer ward, where the director found himself when visiting his sick mother, and Kici, kici (Kitty, Kitty), a seemingly light yet unsettling documentary about caregivers who feed feral cats.

His artistic credo is simple. “A documentary rises out of a curiosity about the world and people. Loneliness is the key. Just as in literature. You read it and think: that’s about me; I feel the same; I’m not alone anymore. And though film is a blunt tool by comparison with prose I dream of it being able to fulfil that role.” A documentary film maker whom Łoziński holds in particular esteem is Sergei Dvortsevoy, author of famous single-take films which look as if they have been stolen directly from reality.

Siostry, a short film shot in one brief session, is an example of a dramatic masterpiece yielded by life itself. In a single scene, two ladies in their 80s sitting on a courtyard bench reveal their whole life together. The older, stronger, sister is proud of looking after the younger one who is lame. She triumphs over her and drills her. She monologues to the camera while the latter submissively walks around a flowerbed in order to exercise her hip, at each round asking her sister imploringly for the key to their flat.

Still from Siostry (Sisters) (1999)Both sisters live their own drama. We can only see what they choose to reveal to us, and can only guess the rest. The younger, weaker, sister is a prisoner of the older, stronger one. This predicament may have lasted all their lives. Now, dependent upon each other, they are prisoners of their old age. Having performed their drama (or black comedy) about life-and-death matters, the two sisters disappear in the depths of the building. The courtyard becomes deserted. A storm, which the younger sister feared and the older ostensibly neglected, has been brewing for a while now. It finally breaks out with a full force closing over the picture like a curtain. What transpires at each minute of the film is the elementary characteristic of cinema whereby reality becomes a metaphor. Every gesture and word gains a double meaning. The absurdity and misery of old age, the relentless fight for life, and the grinning and bearing - all of that finds its form on the screen and is turned into a drama. That is as much as one can do for them. They, on the other hand, seem to enjoy the bit of attention which the camera proffers to them.

Still from Siostry (Sisters) (1999)Both sisters live their own drama. We can only see what they choose to reveal to us, and can only guess the rest. The younger, weaker, sister is a prisoner of the older, stronger one. This predicament may have lasted all their lives. Now, dependent upon each other, they are prisoners of their old age. Having performed their drama (or black comedy) about life-and-death matters, the two sisters disappear in the depths of the building. The courtyard becomes deserted. A storm, which the younger sister feared and the older ostensibly neglected, has been brewing for a while now. It finally breaks out with a full force closing over the picture like a curtain. What transpires at each minute of the film is the elementary characteristic of cinema whereby reality becomes a metaphor. Every gesture and word gains a double meaning. The absurdity and misery of old age, the relentless fight for life, and the grinning and bearing - all of that finds its form on the screen and is turned into a drama. That is as much as one can do for them. They, on the other hand, seem to enjoy the bit of attention which the camera proffers to them.

Still from Taka historia (The way it is) (1999)The same building is home to another outstanding documentary entitled Taka historia [The Way It Is]. The protagonist by the name of Wiesio is an ex-caretaker. Only just past his prime, afflicted with illness but still imbibing, Wiesio rummages through garbage bins which he calls Pewexes (a chain of opulent dollar shops in communist Poland). He and the director (“our Pavelek”) strike up a special rapport. Both Paweł and Wiesio want the film, and the presence of the camera is often brought to attention. The film serves as a proof of their mutual trust and a testament to their friendship.

Still from Taka historia (The way it is) (1999)The same building is home to another outstanding documentary entitled Taka historia [The Way It Is]. The protagonist by the name of Wiesio is an ex-caretaker. Only just past his prime, afflicted with illness but still imbibing, Wiesio rummages through garbage bins which he calls Pewexes (a chain of opulent dollar shops in communist Poland). He and the director (“our Pavelek”) strike up a special rapport. Both Paweł and Wiesio want the film, and the presence of the camera is often brought to attention. The film serves as a proof of their mutual trust and a testament to their friendship.

Wiesio gets together with Zdzisław, an 84-year-old retired hairdresser with slightly pretentious aristocratic manners, haunted by memories of his beloved dead wife. His head appears in one of the ground floor windows. The young man with a camera observes the two older men who, by allowing him to film them, draw him into their drama. A dandy and a tramp (who, too, has a sense of dignity and peculiar elegance) joke and chaff with each other. The duo of contrasting characters build the drama structure and spur the action onward. Both protagonists might not be around for much longer. They might suddenly vanish from the courtyard as if down a trapdoor. They touch on questions of death even when talking about fishing and mushroom picking.

Does Samuel Beckett, the author of Happy Days write the lines for all elderly people? In Malone Dies the protagonist, who has found himself in a cul de sac, hopes to last as long as does his pencil, with which he writes down his thoughts. The camera serves Łoziński as the Beckettian pencil. When asked how he is, Wiesio answers nonchalantly, “Dying.” But Taka historia is not a film about death, and neither is Chemia, although they deal with a series of irrevocable facts such as illness, debilitating addiction or social situation which pushes old people to the social margin.

Still from Taka historia (The way it is) (1999)However, the act of filming is of great value in itself. It is a kind of holy communion or prayer and an act of taking responsibility for another human being. Before the camera, reality gains shape and meaning and becomes more interesting. One doesn’t die in front of the camera, does one? “There was a point where I didn’t care about the film anymore just as long as my characters were alright. Mr. Szymański died in the end but if I hadn’t turned up with my camera he would have been more lonely. This way he told someone his life story.” Łoziński deliberately uses the hairdresser’s amateur videos from a holiday with his wife. They are contrived images of happiness: a forest, lake, smiling wife, heaps of freshly picked mushrooms and two long-gone pooches. Taka historia could, to an extent, be placed on a par with such home videos, because, although it does not shrink from showing some of the darker sides of Wiesio’s life, it somewhat elevates, redeems and exonerates them. This precisely is Łoziński’s notion of the role of the documentary and the camera. While depicting the murkier not to say evil sides Łoziński renounces his role as a judge and denouncer who passes a verdict on his characters. He shares Kieślowski’s belief that a film can do something good, not so much to the world, which would be a conceited ambition, but to the viewer, and the author himself.

Still from Taka historia (The way it is) (1999)However, the act of filming is of great value in itself. It is a kind of holy communion or prayer and an act of taking responsibility for another human being. Before the camera, reality gains shape and meaning and becomes more interesting. One doesn’t die in front of the camera, does one? “There was a point where I didn’t care about the film anymore just as long as my characters were alright. Mr. Szymański died in the end but if I hadn’t turned up with my camera he would have been more lonely. This way he told someone his life story.” Łoziński deliberately uses the hairdresser’s amateur videos from a holiday with his wife. They are contrived images of happiness: a forest, lake, smiling wife, heaps of freshly picked mushrooms and two long-gone pooches. Taka historia could, to an extent, be placed on a par with such home videos, because, although it does not shrink from showing some of the darker sides of Wiesio’s life, it somewhat elevates, redeems and exonerates them. This precisely is Łoziński’s notion of the role of the documentary and the camera. While depicting the murkier not to say evil sides Łoziński renounces his role as a judge and denouncer who passes a verdict on his characters. He shares Kieślowski’s belief that a film can do something good, not so much to the world, which would be a conceited ambition, but to the viewer, and the author himself.

Chemia, one of Łoziński’s greatest films, emanates an ardour for life in defiance of death, evil and the inexorable. It epitomise the battle of hope against hopelessness. The title relates to cancer treatment as well as to human chemistry - closeness, solidarity and understanding. The director doesn’t try to shock the viewer with hospital scenes or physiology. The patients take their doses of chemicals but we don’t see the drips with the colourful fluid that is meant to kill their cancer cells. We see their faces from close up. They lie on beds in pairs. They talk. Through careful editing Łoziński creates the impression that they are together, gathered in one circle and listening to one another. The act of filming, which this time is not made obvious to the viewer, creates intimacy. We listen to them from a distance so close as if we were sitting on the side of their beds. We experience the wonderful charm of these people. Why do those who suffer radiate so much hope?

Still from Chemia (Chemistry) (2009)In his film Łoziński touches upon the very mystery Thomas Mann spoke of in his Magic Mountain and Dostoyevski in The Idiot, namely that when seen from the other side, life reveals itself in all its worth and meaning. Why only then? And could one hold onto this feeling? From the perspective of a hospital bed the blocks of flats outside the window seem like oases of happiness. If only one could go back there… The film ends with a return to the world. Having had their chemotherapy, the characters walk through the hospital’s glass doors - some with a full acquittal, others with a suspended sentence. And yet again, we see a gallery of unforgettable distinct faces of life’s actors: the voluptuous Ela who runs a “fruit and veg salon” in the Mokotów district, the intellectual in tinted glasses and the young woman who are exchanging thoughts on their culinary favourites, and the nun who is just as perplexed about the sense of suffering as everyone else. A young man with testicular cancer who is about to get married hasn’t ordered his suit yet because he’s been loosing weight. He hopes that things will turn out fine for him and his red-haired girlfriend, mother of their new-born baby, who is lying next to him. If it was not for their headscarves, wigs and hats they would be showing no visible signs of illness. Removed from the timeline, they talk in front of the camera as if they were outside both life and death. Just like Wiesio from Taka historia they dart from jokes to solemn matters. They comfort each other. This film has nothing to do with observing illness or suffering. It arouses a sense of solidarity with the characters. “How could this have happened to me? I have so much to do in this life. For me, it’s not about fighting. It’s about winning!”

Still from Chemia (Chemistry) (2009)In his film Łoziński touches upon the very mystery Thomas Mann spoke of in his Magic Mountain and Dostoyevski in The Idiot, namely that when seen from the other side, life reveals itself in all its worth and meaning. Why only then? And could one hold onto this feeling? From the perspective of a hospital bed the blocks of flats outside the window seem like oases of happiness. If only one could go back there… The film ends with a return to the world. Having had their chemotherapy, the characters walk through the hospital’s glass doors - some with a full acquittal, others with a suspended sentence. And yet again, we see a gallery of unforgettable distinct faces of life’s actors: the voluptuous Ela who runs a “fruit and veg salon” in the Mokotów district, the intellectual in tinted glasses and the young woman who are exchanging thoughts on their culinary favourites, and the nun who is just as perplexed about the sense of suffering as everyone else. A young man with testicular cancer who is about to get married hasn’t ordered his suit yet because he’s been loosing weight. He hopes that things will turn out fine for him and his red-haired girlfriend, mother of their new-born baby, who is lying next to him. If it was not for their headscarves, wigs and hats they would be showing no visible signs of illness. Removed from the timeline, they talk in front of the camera as if they were outside both life and death. Just like Wiesio from Taka historia they dart from jokes to solemn matters. They comfort each other. This film has nothing to do with observing illness or suffering. It arouses a sense of solidarity with the characters. “How could this have happened to me? I have so much to do in this life. For me, it’s not about fighting. It’s about winning!”

Can this humanistic belief be also found in Łoziński’s famous debut Miejsce urodzenia (Birthplace)? Writer Henryk Grynberg returns from the U.S. to the village where he and his family were hiding during the occupation and where his father Abram was murdered. In the early 90s the film fit in the vast and endless debate about the responsibility of the holocaust witnesses. As in Grynberg’s writing, Łoziński takes the Jewish tragedy out of the realm of abstraction and turns it into a concrete event. He seeks to answer Grynberg’s question of, “how could people do this to the Jews?” Walking from house to house on a bleak winter day, Grynberg looks people in the eye and asks about the circumstances of his father’s and brother’s death. He seeks to learn the truth, and he does in the presence of the camera. We learn who killed Abram Grynberg, we find his remains and the very milk bottle he had on him.

Still from Miejsce urodzenia (Birthplace) (1992)As one of the villagers says, “there’s the good and the evil folk.” The film tries to encompass that “good and evil” by observing the faces of the people Grynberg meets in his home villages. Account after account, the people fill in the details of the atrocious truth and become more and more disparaging of the “local folks”, and thus, to a certain extent, of themselves. “Those Jews were our people but you couldn’t hide them because your neighbours would rat on you.” Another speaker bursts out, “Our folks killed them, our folks, not the Germans! Christ! Our sons of bitches were there!” Łoziński peers at the human countenances trying to discern any traces of humanity such as shame, regret or guilt in both the witnesses and those who partook in the atrocities. It is in that observation where the profound sense of this film lies. And here lies the principle of Łoziński’s camera.

Still from Miejsce urodzenia (Birthplace) (1992)As one of the villagers says, “there’s the good and the evil folk.” The film tries to encompass that “good and evil” by observing the faces of the people Grynberg meets in his home villages. Account after account, the people fill in the details of the atrocious truth and become more and more disparaging of the “local folks”, and thus, to a certain extent, of themselves. “Those Jews were our people but you couldn’t hide them because your neighbours would rat on you.” Another speaker bursts out, “Our folks killed them, our folks, not the Germans! Christ! Our sons of bitches were there!” Łoziński peers at the human countenances trying to discern any traces of humanity such as shame, regret or guilt in both the witnesses and those who partook in the atrocities. It is in that observation where the profound sense of this film lies. And here lies the principle of Łoziński’s camera.

translated by Aneta Uszyńska