“I never realized how many words were needed to cover the confusion in my mind. A confusion that immediately eludes any words found to describe it,” writes Herta Müller. “And yet I have always had this urge to ‘Say it.’” Her words sound like more than just desire: they sound like compulsion.

Herta Müller endlessly tells the story of her own biography. She cuts words out of newspapers and pastes them into collage-poems, she quotes her own books and stories in essays; the same events, the same objects, the same people and words all come back insistently ― in various configurations ― throughout her writing. The past is relentless. Not only does it refuse to go away, it constantly demands renewed efforts to name that which has no name. It demands our full attention, extreme discipline, and faithfulness to a particular experience, while requiring us to perform the mental gymnastics necessary to disassemble and reassemble it, each time anew.

So what is the theatre to do with this heap of quality words, piled on to “cover the confusion in the mind”, with this experience that cannot be expressed through these words, with this dramatic biography, which, recorded on the pages of books, takes on even greater meaning?

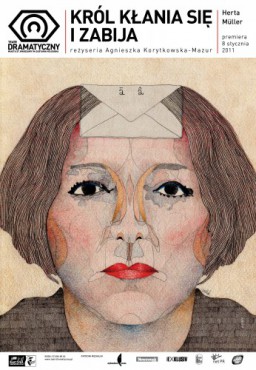

The screenplay for The King Bows and Kills has been compiled from different bits and pieces of Müller’s writing. The authors of the adaptation, director Agnieszka Korytkowska-Mazur and Magda Fertacz, have chosen to use the collage technique, a reflection of Müller’s own use of newspaper cutouts in her poems. The pair focused on painting a synthetic, unapparent picture of the writer, rather than simply conveying a selection of biographical elements, or rather than searching for the theatrical equivalent to essential and sagacious paragraphs of her prose. They also opted for brevity and terseness. The whole show lasts maybe an hour, no more. There are no spectacular scenes, and there isn’t much in the way of words; anyway, they’re usually not the words that we would underline while reading. But there is a lot of music ― ethnic music, performed live.

Herta Müller is portrayed with three faces. As if to subversively play on the original German title of The Appointment, which translates to “I’d Rather Not Meet Myself Today”, the three Hertas meet in the very first scene. Each wearing a black wig, pale, somber, with accordions in their hands. There’s Herta the child, played by Klara Bieawka, a little girl brought up on the plains of Romanian Banat, among German peasants, in a home without a single book. Then there’s young Herta, played by Agnieszka Roszkowska, who has moved to the city, goes to university, has a husband and serious problems with the Securitate. And finally, contemporary Herta (Beata Fudalej), who has lived in Berlin for years, becoming an accomplished writer and recent Nobel Prize laureate. This last Herta, the oldest one, sets the mood and sticks firmly to the rhythm of the three-tone melody played on the accordions.

The decision to triple the main role is a key element in the play. It makes time more dense and strips chronology of any significance. What it achieves is more than just a banal narration of memories, it is a coexistence of the past and the present, in the same moment and on equal grounds. The time warp technique aptly conveys the phenomenon of irreversible scarring by the past described by Müller. Time eludes any linear arrangement, any succession of cause and effect, branching out instead in all directions. The past is still happening, Müller says, ready to attack and materialize in full detail as a nightmare, at any moment and for any reason.

The flat space retains nothing of the relentless memories aside from a long, filthy wall and an improvised swing door. Poverty and squalor. The interior also serves as an interrogation room, a waiting room, a train corridor, and a childhood home; two meager photographs hang on the peeling, patterned wallpaper: a family picture and a cow in pasture.

Everything, we may assume, is happening simultaneously. A train passes by, its illuminated windows flickering on the face of little Herta as she stands in a corn field, dreaming of one day having asphalt under her feet, and holding a severed finger wrapped in a bloody rag, resembling a rat found in the cucumber patch; it is also an unspoken reminder of torture, threats, the deaths of friends, and constant fear. Wendel (Sławomir Grzymkowski), a childhood friend with whom she plays house, has a spot reserved in her memory, next to her real husband Paul (Henryk Niebudek), who reeks of vodka but offers her support. Nor can she free herself of her screaming, obsessive potato peeling mother (Ewa Telega), who haunts her daughter even when Herta is a successful writer appearing on TV. Barely having finished answering the questions of a stupid, dense journalist, Herta must once again listen to her mother’s complaints, asserted into the same microphone. Her father, a former SS officer, wears knee-high military boots and breeches, which also go perfectly with the Securitate officer played by Miłogost Reczek. Her grandfather (Maciej Szary) is also a chess king. After all, the true name of the dictator-king must not be uttered, just as the word “checkmate” is used instead of “death”, and the game goes on.

Memory takes things out of context and combines them into new, broken and disconnected patterns. Agnieszka Korytkowska-Mazur does the same with the writing and biography of her subject. Her picture of Herta Müller is one of many possible portraits ― not necessarily the most adequate one. But it isn’t very obtrusive either, and is actually quite modest. Perhaps this is the source of the unfulfillment one feels when the curtain falls. The play lacks determination at times, the kind of determination found in Müller’s “Say it”: definitive and tenacious ― the kind of determination made possible by ruthless literature and the biography of a relentless woman.

You can see by her face and gestures that the oldest Herta has grown weary of her memory’s cruel mind games. But she still has the energy to mock the conventions ― in a liberated, dancing final monolog ― and show her defiance and class as an outsider. But this manifestation of internal freedom makes no impression on her audience. “Thank you for awarding me the Nobel Prize,” says Herta, not without irony. The characters gathered by the gray wall respond as one, nonchalantly, “You’re welcome.” She isn’t the first crazy writer we’ve seen. She was strange and she will remain strange.

The cruel humor of this ending contains the stifling ruthlessness that one would like to see throughout the entire play.

translated by Arthur Barys