MAGDA CHOŁYST talks to ŁUKASZ BARCZYK

MAGDA CHOŁYST: Your latest film, Italiani, came out in theatres two weeks ago. Have you read the reviews?

ŁUKASZ BARCZYK: I have.

There’s no doubt about the fact that you’ve made an exceptionally original film in formal terms. But the jury’s still out on whether there’s any content behind the images. Łukasz Barczyk and his actorsNinety nine percent of all films grab the audience by the face. Filmmakers keep pulling tricks in a constant effort to impress viewers and keep them in front of the screen. When your film requires a certain level of cooperation on the part of the viewer, there’s always the risk that the viewer simply won’t collaborate. This can happen for a number of reasons. They might not like the aesthetics of the film, their sensibilities could be different, or they just might not be in the mood. Film is something that occurs where the screen and the audience come together. As a filmmaker, you always run the risk of experiencing interference on that plane, but that’s the entire point of making movies – otherwise, everything would be predictable. When I was making Italiani, I thought it would be fascinating to shoot a movie that wouldn’t guide the audience, one that wouldn’t impose any emotion or interpretation. But if the viewer refuses to cooperate, then the interaction vanishes and all that’s left are empty images.

Łukasz Barczyk and his actorsNinety nine percent of all films grab the audience by the face. Filmmakers keep pulling tricks in a constant effort to impress viewers and keep them in front of the screen. When your film requires a certain level of cooperation on the part of the viewer, there’s always the risk that the viewer simply won’t collaborate. This can happen for a number of reasons. They might not like the aesthetics of the film, their sensibilities could be different, or they just might not be in the mood. Film is something that occurs where the screen and the audience come together. As a filmmaker, you always run the risk of experiencing interference on that plane, but that’s the entire point of making movies – otherwise, everything would be predictable. When I was making Italiani, I thought it would be fascinating to shoot a movie that wouldn’t guide the audience, one that wouldn’t impose any emotion or interpretation. But if the viewer refuses to cooperate, then the interaction vanishes and all that’s left are empty images.

Is form even a topic of discussion in Poland?

No one talks about form at all. Our discussions revolve around scripts, around the stories that filmmakers want to tell. And of course, we talk about Poland and Polish reality. Meanwhile, film is language, form, and style. When I watch French, American, or Asian movies, I get the impression that they’re not too preoccupied with reporting on the state of reality. They’re more focused on reporting on what goes on inside us. Directors such as Kim Ki-duk and Gaspar Noé don’t shy away from extravagance and taking formal risks. They don’t strive to describe reality. Does Gaspar Noé make films about France? If a movie of his features a rape scene in a pedestrian underpass in Paris, does that mean he’s telling us about France? Or take Enter the Void: if the events take place in Tokyo, does that mean the movie is about Japan? These aren’t films about the real world, nor are they about France or Japan. We don’t just live in Poland anymore. It’s time we abandoned the notion that we have any obligation towards Poland. Our obligation is to make good films. Until something changes here, filmmakers are going to continue to believe that they’re expected to tackle issues that involve describing reality. Then viewers will watch these movies and get stuck at the level of the screenplay, thinking to themselves whether the film was a faithful rendition of reality. This leads to a vicious cycle. Of course, I don’t mean to say that I’m the only one doing things differently – that would be ridiculous. People make movies however they can and however they feel they should.

Does it annoy you that the Polish Film Institute continues to support historical films?

That’s just cultural politics, and politics always freaks me out.

How would you suggest we discuss form in film?

If people want to talk about a film, it means that they’ve somehow been moved, touched, pissed off, or offended by it. Emotions are a prerequisite for any discussion at all. But if we’re going to talk about film, I’d rather we use our intellect and start calling a spade a spade. I want us to stop discussing what films talk about and start discussing what films are. How they use sound to tell a story, what happens in the images, what goes on in the editing, what the shots were like, how the scenes and sequences were staged. I don’t want to listen to all that sappy drivel about how a movie is all about people being lonely and needing love.

Before we talk about form in Italiani, I have to ask: how did all of you end up in a Tuscan villa?

Karina Kleszczewska, my wife and camerawoman, was exhausted after shooting footage for the film Tea in Slovenia. We decided to drive down to the south of Italy. As we were crossing the Italian border, I called up an old friend of mine, Jacek Poniedziałek, just to find out what he was up to. It turned out that he was in Tuscany, along with Małgorzata Szczęśniak and Krzysztof Warlikowski. As luck would have it, they ended up in a villa in Montebamboli. Since it was the day before Jacek’s birthday, we decided to join them.

As we were exploring the area one night, I saw Małgorzata, Karina, Jacek, and Krzysiek standing next to each other, and I thought to myself: “We’re going to make a movie here.” Krzysztof and I started working on a script and getting people on board. Renate Jett came over from Switzerland. Margherita di Rauso cut her Greek vacation short just so she could join us. Thomas Schweiberer happened to be in a nearby Italian Buddhist monastery at the time. Meanwhile, we were busy piecing together the equipment, which arrived, along with Karina’s assistant, in a truck, just two weeks from the moment we decided we were going to make a film. And that’s how we all ended up on location.

What was the artistic process like, from the visual standpoint?

Just the usual, but in fast-forward. Once the screenplay is ready, Karina and I sit down and come up with images that would be the equivalent of what we were trying to get across. We do a shooting script, a storyboard, and design all the details of the film. We vet everything on set, but we usually stay with most of our ideas. With Italiani, the shooting script was put together pretty quickly and was very simple. We decided that the space and the people we had there were so strong that we needed to find simple, credible techniques like the ones used in old movies, where the staging only got you so far. We didn’t use any dollies or jibs, because we didn’t have the equipment. We just had to make do with a very rudimentary kit.

You and Karina form a director-camerawoman duo. How does that work out for you?

Both of us are hard to work with, but vision isn’t what we argue about. We strive to achieve a certain result, and when it doesn’t work out, we get tense and start arguing. We argue a lot. But we usually know what we’re looking for, and we both know when we get it. Then we go on to production, and have a lot of fun doing it. Italiani, dir. Łukasz Barczyk. Poland 2010As your wife, is Karina better able to convince you to agree to things that she can later do as your camerawoman?

Italiani, dir. Łukasz Barczyk. Poland 2010As your wife, is Karina better able to convince you to agree to things that she can later do as your camerawoman?

Our professional relationship goes back further than our personal relationship. We’ve been together for five years, and we shot our first movie together 15 years ago, so we’ve had time to find some stability in our professional relationship. Besides, our artistic exploration isn’t driven by the need to have fun or experiment. The story we have to tell is the sine qua non of making a film. The form is intended to be an internally cohesive medium for that content. Even if we a find an interesting technique, we’ll give up on it and keep on looking if it doesn’t rhyme with the language of the film. Despite its references to a huge number of languages and genres, Italiani is internally cohesive.

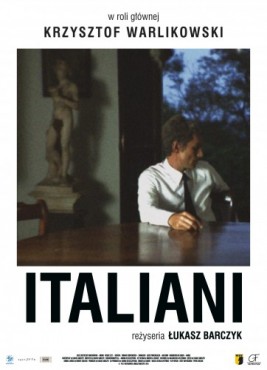

How does the director Krzysztof Warlikowski fare as an actor?

Krzysztof is the perfect actor. The perfect actor is someone with the ability to behave intelligently and authentically even in the most difficult situations. They have to be interesting people, regardless of how you look at them, because a person’s appearance, their physicality, is really all that’s left of them on screen. Krzysztof is an exceptionally intuitive actor. He’s an interesting and experienced director, and a wise, beautiful person. Working with him was an explosion of sorts, an initiation into a different reality that I hadn’t been to before. It was a very inspiring experience.

Were there any moments when you disagreed?

No. Well, maybe two. Our collaboration was based on enormous trust, so those two incidents aren’t even worth mentioning, especially since we’re both happy with the results.

Both of you had already worked on Shakespeare productions. Who came up with the idea of developing the theme of the Oedipus complex in Italiani?

It was an obvious choice to us. Having worked on Hamlet, we knew what was left to be done. But Italiani is not Shakespeare. I’m saddened by the reviews that say I’ve pauperized Hamlet. There’s not a word about Shakespeare in my film, and my protagonist is named Bruno. I simply employed a motif, a theme, the same one Shakespeare used to construct his own play. Everyone falls into this trap. Interpreting Bruno as Hamlet helps people find their ground in the story, it gives them a sense of security and helps them decode the events on screen. But Bruno, who lives in the ‘30s, is an educated man and has probably read Hamlet. And that’s precisely where the strength of the film lies, in that the protagonist recognises his own myth. He takes part in the spectacle that life has forced him into, but he refuses to co-participate. He refuses to be Hamlet, in a sense, while at once being him.

You once said that one cannot improvise film, nor can it be born out of discussion. But with Italiani, there was quite a bit of room for improvisation as well as discussion.

This film wasn’t improvised. When Krzysztof and I decided that we were going to co-author the screenplay, which took two weeks, then it’s only natural that we were in a constant creative state, talking and agreeing on what we were going to do next. Whenever we had differences in terms of concept, we would do both versions, and I would make the final call in editing, as the director. But such situations were the exception. When I have a screenplay that I’ve been working on for two years, there’s nothing to talk about, I just have to make the film.

Yet when I imagine you in that Tuscan villa, discussing the best way to shoot a three minute scene for four hours, I get the impression that the movie was made in a creative laboratory, rather than a restrictive film set.

We were very open to the situations we encountered. Our freedom resulted

from a lack of expectations. We didn’t know whether we would ever finish the film. We wanted to make it as best as we could in the conditions at hand. Our Tuscan adventure was an intellectual and spiritual meeting of sorts, one that we found to be a valuable experience in itself. But we also had a specific plan to fulfill. We had a script and we demanded a certain discipline of ourselves. We knew what we were going to do every day and how much time we had to do it.

Production took you a total of four and a half years.

Time was another cost that we had to bear in order to see the project to the end. What was that time? It was my own work, work usually done by a team of ten people. It was my life, the cost I paid to remain independent of state funding.

Italiani is your second solo production. The Błyskawica Film Company was founded during the making of your previous film. What was the story behind that?

The screenplay to Unmoved Mover was troublesome because of how it portrayed the subject. The story of a rape without an unambiguous indication of the perpetrator and victim was unacceptable. Stories about the dark side of human nature have no place in Poland. And when they do, it’s always a zero-sum game. People are always either good or bad, and rarely is it pointed out that the cause of the problem lies elsewhere, that the balance is different. Aside from the controversy over the subject, there was also the issue that no one knew just what form I would give the film. I didn’t get funding, so I produced it myself, and everyone who worked with me invested their time and energy in return for an unknown reward. I managed to receive funding from the Polish Film Institute later on, in post-production, but Unmoved Mover was a risk we all took.

Is your professional life easier now that you have your own company?

I would say it’s become more difficult. Launching Błyskawica wasn’t a question of choice, it was more an act of desperation. Making films out of your own pocket isn’t convenient, it’s a necessity. I don’t want to complain, I’d rather just make movies. But I won’t say that my situation is perfect. I’m no Hearst. Everything I’ve been earning, I invest in film. That’s no cause for celebration. I’d rather have a producer whom I could pay to take care of me. The way things are now, I have to take care of myself.

But at the same time, you can afford to be independent.

There’s no such thing as independence in the film industry. Directors are dependent on everything: an actor’s mood, the weather, the money. There’s no such thing as independence in this profession. Poets can be independent. My job comes down to being dependent all the time and knowing how to balance all these dependencies while still remaining myself. If I have any semblance of freedom, it’s thanks to the great number of people who want to help me out and do something outside the system.

Didn’t it make you feel independent when you refused to submit Unmoved Mover to the Gdynia Festival, as an act of defiance?

There are certain advantages to making your own films. I don’t have to consult what’s going on in my films with anyone. In that sense, it does give me comfort and independence. I don’t have to worry about whether someone will let me do something or not. I still hope I’ll be able to work on my next film in better conditions.

You’ve mentioned a project you’ve been working on with Kadr Studio, Soyer. Can you reveal any details?

Life has taught me not to talk about movies until I’m actually on set. Movies are made when they’re made, not when you’re still thinking about them and planning. It’s an unwritten rule.

Never mind then. Thank you for the interview, and good luck on your next movie.

translated by Arthur Barys