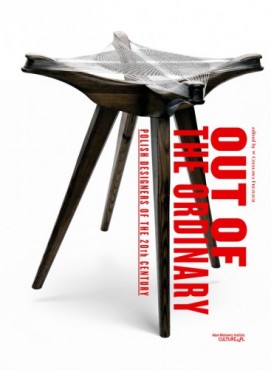

I hold in my hands the voluminous tome Out of the Ordinary. Polish Designers of the 20th Century. This exceptional book has been published in English by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute (although a Polish edition is in the works). It contains a collection of essays, edited by Czesława Frejlich, devoted to outstanding 20th century Polish designers, from Stanisław Wyspiański and Stanisław Witkiewicz, through Karol Stryjeński, the avant-garde couples Helena and Szymon Syrkus and Barbara and Stanisław Brukalski, to Maria Chomentowska and Andrzej Pawłowski as well as Jerzy Antkowiak and Barbara Hoff. The articles — most of which appeared previously in the magazine “2+3D” — have been arranged into five parts. Each part is preceded by a brief introduction penned by David Crowley, a specialist on Central and Eastern European industrial design and curator of the widely-discussed London exhibition “Cold War Modern. Design 1945–70” (Victoria & Albert Museum, 2008). The book itself is decently designed (although some might find the typography a bit old-fashioned), and features quite impressive illustrations.

The authors open the history of design with the early attempts at creating a Polish national style prior to 1918 (the Zakopane style, Wyspiański) and in the first years of independence (the Kraków Workshops), before moving on to state-commissioned design in the Second Polish Republic. The story is relatively well known and has been widely discussed.

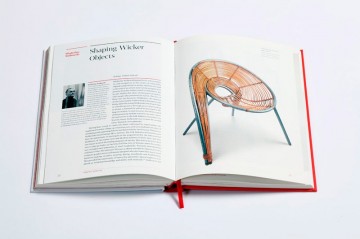

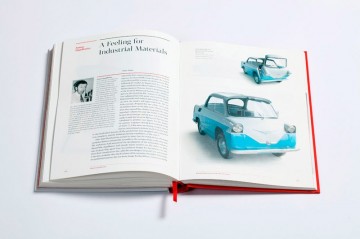

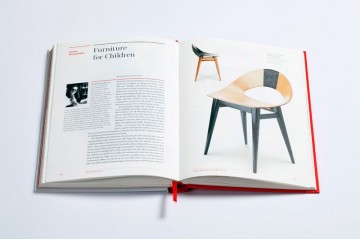

The chapters devoted to design in the People’s Republic of Poland aren’t quite as outstanding. One might get the impression, having read them, that post-war designers focused their efforts exclusively on particular objects and their own narrow fields, such as wicker, ceramic, or fabric. The section lacks a bio of Jerzy Sołtan, nor does it devote much space to the Art and Research Center at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. Paradoxically enough, pre-WWII design, while created with craft production in mind, is described instead as an intellectual endeavor inscribed into the context of its era. Post-war design on the other hand, developed for the purposes of industry, is narrowly defined as an activity detached from practice or ideas.

graphic project by Kuba Sowiński

graphic project by Kuba Sowiński

The authors have also ignored the latest trends in research on the visual culture of socialist Poland. It’s a pity, considering the great attention devoted to the phenomenon of advertising in the People’s Republic of Poland, especially with regards to neon signs, an important element in the image of the modern city. A number of exceptional shows have also been held in recent years, such as the presentation of exhibition designs by Stanisław Zamecznik, held as a part of the Warsaw Under Construction festival (Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2010). These themes have been overlooked in the book, which might as well have been published 10 years ago.

A history of objects or a history of ideas?

In result, Out of the Ordinary simply perpetuates the propagandistic myth of Poland as a modern country, a myth built up through years of international exhibitions. The introduction by Czesława Frejlich even states that “The contents of this book will help readers grasp the value and originality of Poland’s material culture.” Meanwhile, in the introduction to the chapter on post-war design, David Crowley writes that “The modern character of the thaw was more frequently expressed through paintings than objects. Only a small number of the projects created in state design institutions ever went into production. […] Despite the propaganda of success enshrouding design, neither the IWP [Institute of Industrial Design] nor any other design institutions ever became successful parts of the planned economy, and the nationalised industrial sector was habitually uninterested in innovation. Yet these products were widely publicised and exhibited in Poland and abroad. To put it briefly, modern design gave Eastern Bloc socialism a certain liberal elegance.” Nothing more, nothing less.

Nearly all of the designers presented in the book share a common trait: most of their designs never saw the light of day. The photographs depict prototypes and museum exhibits. By focusing on distinguished names, the authors overlook the original character of visual culture in the People’s Republic of Poland and the ideological factors that played a role in the designer’s work. In their depictions of particular figures, the authors failed to take into consideration David Crowley’s fundamental thesis: “The history of design tells the story of not just objects, but values and ideas.”

The same mistake was made at the National Museum of Warsaw, where crowds queued last winter to see the exhibition “We want to be modern”. Instead of focusing on the material culture of the People’s Republic, they chose to emphasise a particular vision of the period. Seen from the perspective of the museum, the 60s and 70s look dazzling. And yet the bulk of the output of the two decades consists of tacky wall units, even if they were occasionally decorated with porcelan figurines from Ćmielów. The first edition of the Warsaw Under Construction festival (2009), however, did address this issue. The Museum of Modern Art put on an exhibition of prototypes from decades past at the Emilia furniture salon, a presentation that also featured the latest work of young designers. The exhibition contrasted with the store’s regular stock, raising the question: why is that the case?

Why are our apartments so hideous, so repulsive?

By mythologising the past, we forget about the fundamental purpose of design: better living. I would like to see books on design deal not just with the designers and their objects, but also serve as springboards through which to discover the users of these objects. I would like to read the history of design as a story of phenomena and ideas in the broad field of material culture, rather than just the history of prominent figures and artifacts, as in the popular Art Now series of books. Otherwise, we will remain torn between self-satisfaction and pride in the achievements of Poland, and complaining that so little has remained of their success.

***

A few days after the release of this review, we received the following comments from the book’s editor, Czesława Frejlich.

As the editor of Out of the Ordinary. Polish Designers of the 20th Century, published by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute, I feel obligated to respond to the criticism presented in the review.

Karol Sienkiewicz writes that “The authors have also ignored the latest trends in research on the visual culture of socialist Poland. It’s a pity, considering the great attention devoted to the phenomenon of advertising in the People’s Republic of Poland, especially with regards to neon signs, an important element in the image of the modern city.” I did, in fact, completely omit the applied arts. This was an entirely conscious choice on my part, as we are currently preparing a second volume devoted precisely to this subject. Excerpts have already appeared in the magazine “2+3D”.

The author goes on to write, “The section lacks a bio of Jerzy Sołtan, nor does it devote much space to the Art and Research Center at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts.” As I mentioned in the introduction, the selection of designers was based on their particular disciplines. Despite his incontrovertible contributions to the field, such as the foundation of the Department of Industrial Design at the Warsaw Academy of Fine arts, Jerzy Sołtan was an architect (see list of works, Jerzy Sołtan, ed. Jolanta Gola, Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts Museum, 1995). Many other distinguished artists have been omitted for the same reason.

Writing about Polish design prior to the end of World War I, the author states, “The story is relatively well known and has been widely discussed.” In my opinion, the story of Polish design is not well known at all, much less widely discussed. My experience shows that there is much primary research to be done, and not just on the post-war period. Furthermore, researchers have a tendency to approach applied art and industrial design from the perspective of art history, without using the tool of analysis appropriate to phenomena of this type. Despite the size of our country, we don’t even have a proper museum devoted to industrial design. The collections of the National Museum stored away in Otwock are not available to the public, nor are researchers given easy access to them. What more, no policies have been implemented to acquire new exhibits. The reason behind this is that we often treat objects with disdain, failing to appreciate handicrafts. We lack a culture of production. In order to “read the history of design as a story of phenomena and ideas in the broad field of material culture, rather than just the history of prominent figures and artifacts, as in the popular Art Now series of books,” as the author proposes, we must first discover the things that constitute the foundation of design before attempting generalisations about the phenomena. The volume contains over 250 photographs, most of which were specially taken for this book. The objects depicted were obtained from museum storerooms as well as private collections. The book also features archival images from old publications that could only be tracked down by writers conducting research for monographs about a given artist.

Let me end by addressing the most serious criticism, contained in the following sentence: “The latest trends in research on the visual culture of socialist Poland (…) have been overlooked in the book, which might as well have been published 10 years ago.” While this may be true, no such book as yet been published.

Czesława Frejlich

translated by Arthur Barys