Clad in traditional leather Malian garb and a playful hat, the African sculptor Yossouf Dara smiles in a picture on the front page of the weekend section of the local paper. He was photographed at work, squatting over a rough-hewn tree trunk. The caption below the image announces: “Africa comes to Bródno”. The paper promised an exceptional event.

Toguna

Paweł Althamer, Toguna, 2011

Paweł Althamer, Toguna, 2011

photo: Bartosz Stawiarski /

Museum of Modern Art in WarsawOn a overcast mid-July day in Bródno Park, right by the Szpital bus stop, a small crowd gathered: some set up lawn chairs, others stood around, while more curious spectators tried out the toguna. A toguna is a traditional meeting place found in Dogon villages. A few squat, sculpted posts support a thick, thatched roof. The artist, Yossouf Dara, like the builders of the Palace of Culture in years past, incorporated local motifs into his project. One of the pillars holding up the rook features a bas relief of the Warsaw mermaid, her face covered with a kanaga, a traditional Dogon mask.

Members of the Targówek borough government were on hand to deliver speeches at the official event, along with curators from the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, an official sponsor of the transformation that will turn Bródno Park into Sculpture Park. The process began in 2009 with the unveiling of the first pieces, including work by Monika Sosnowska and Olafur Eliasson. The Malian sculptor spoke to the crowd in French, explaining the significance of the toguna. In Africa, village elders gather in the structure to resolve family disputes and make important community decisions. The low roof of the toguna guarantees peaceful discussions: anyone who suddenly stands up in anger will bump their head on the ceiling. “That‘ll calm him down, at least for a little while”, added Dara.

After the official portion of the program, the audience moves over to the area around Rirkrit Tiravaniji’s “Teahouse”: a metal cube balanced on one of its corners. The structure was recently taken over by Michał Mioduszewski. Tiravanija is known for his custom of preparing meals in galleries. Mioduszewski follows in his footsteps, selling coffee, tea, and candy in the cube on weekends. Customers pay whatever they want. The bar has a competitor tonight: the Museum has prepared free refreshments. Bródno denizens crowd around a table of wine glasses and salads.

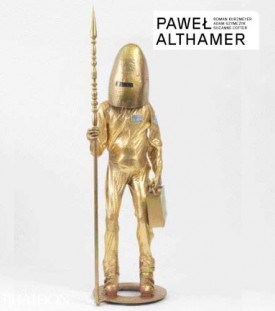

Yet the mastermind of the whole affair is nowhere to be seen: artist Paweł Althamer is out of town, attending an opening of his exhibition. Althamer is the same artist who got his neighbours in his apartment building at Krasnobrodzka 13 to welcome the new millennium by lighting up their windows to form the number “2000”. Then came the renovation of a playground, trips to Brazil, Brussels, and Mali with his neighbours, all dressed up in sci-fi style, gold costumes (“Common Task”), and the Sculpture Park. Althamer met Yossouf Dara during one of his trips to Dogon country and decided to invite the sculptor to Poland. Almost everyone in Bródno knows Althamer.

A shaman and an artist

Roman Kurzmeyer, Adam Szymczyk,

Roman Kurzmeyer, Adam Szymczyk,

Suzanne Cotter, Paweł Althamer

Phaidon Press, London, 2011,

160 pages, in English,

in bookstores from June 2011The art-book publishing house Phaidon recently devoted an entire title to Althamer, thus inducting him into the club of modern classics featured in the “Contemporary Artists” series. He is the first Polish artist to earn the distinction, which he shares with a host of famous names, from Marina Abramović and Vito Acconci to Lawrence Weiner and Franz West. But Althamer is somewhat unbefitting of the term “classic”.

I was fascinated by the juxtaposition of the interviews conducted with Althamer by Artur Żmijewski (author of the book Trembling Bodies: Conversations with Artists) and the interview by Adam Szymczyk, published in the Phaidon book. In Żmijewski’s piece, Althamer assumes the role of a “shaman”, talking about his dreams and drug-induced visions. The pair shot a series of films a few years back, depicting Althamer’s journeys into his own mind. He is assisted by drugs, a truth serum, and a hypnotists. In the course of one hypnosis session, the artist discovers that he was a Jewish boy named Abramek in a previous lifetime. He sees himself in the smoldering ruins of Warsaw, accompanied by a dog named Buruś. Althamer later transformed this vision into a sculpture which now stands in front of his building at Krasnobrodzka 13. Abramek holds a real stick in his hand. The neighbours borrow it when they take their dogs out on walks.

Paweł Althamer, Abram and Buruś,

Paweł Althamer, Abram and Buruś,

2008, courtesy of Foksal Gallery Foundation

In the interview by Adam Szymczyk, director of the Kunsthalle in Basel, Althamer speaks as a professional artist, one whose work is displayed by galleries and museums, one with a certain standing on the art market. My previous impression was that Althamer avoided issues such as these, preferring instead to hide behind institutions and exploit them to his own ends. But in the Szymczyk interview, he makes the following remark: “The context of my activity as an artist has changed. All of the sudden, I’ve adapted to and become a part of the art world. I take part in too many exhibitions to enjoy each one, but I’m still excited when I’m given the conditions I need and when I get invited to take active part in the process.”

Open form

I wonder how Althamer manages to strike a balance between his internal trips and his social projects; how he combines introspection with participation. These attitudes seem to lie at opposite ends of the artistic spectrum. The artist confirms my suspicions about this tenuous balance, invoking the Christian motto: “Love thy neighbour as thyself.” “We often forget about the second part of that commandment,” he says. The commandment of love also tells us to love ourselves.

Paweł Althamer, Cardinal, 1991

Paweł Althamer, Cardinal, 1991

courtesy of Foksal Gallery Foundation

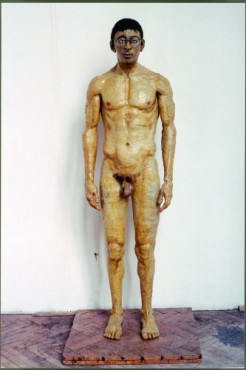

Althamer is one of the few mainstream artists who continues to employ tradition methods of sculpting. The human figure, especially the self-portrait, remains a central theme in his work. By collaborating with others, and often receding into the shadows, Althamer has managed to produce a signature style, one whose roots lie in the work of his mentor, Grzegorz Kowalski, and Oskar Hansen’s concept of Open Form. Kowalski spoke of a “potential form”, opening up his artistic activities to the participation of others beginning in the 1970s. The questions he posed were existential in nature: “Do you wish to return to your mother’s womb?” he asked a group of men, whom he then photographed naked in bathtubs. It was he, however, who made the crucial decisions and shaped the form. Althamer’s approach to form is often lackadaisical, much to the chagrin of the critics.

A specific type of divergence occurs in “Common Task”. Althamer doesn’t settle for one vision of the events, nor does he express much interest in documenting the events. Hence the doubts surrounding the trailer for the Jackass-style film shot by Cezary Ciszewski, one of the participants of the trip to Mali. But playful motifs are a common occurrence in the events associated with Althamer’s work.

Paweł Althamer, selfportrait, 1993

Paweł Althamer, selfportrait, 1993

courtesy of Foksal Gallery FoundationOn the other hand, there’s no telling what would happen if Althamer, who collaborates with enough people as it is, were to attempt to control how others write about his work, how they document it, and how they display it. It would probably push him to the brink of insanity. Many artists like to micromanage their exhibitions down to the last square inch, picking out their own promotional photos and carefully checking their interviews. They fear for their image. Althamer is not one of them, which is why he is sometimes accused of amateurishness. His “weak”, random documentation isn’t worth much in the eyes of the gallery, the market, and the museum. But it isn’t necessarily a sign of disdain. It also stems from his courage and trust in others. Althamer has long done away with fear. Especially the fear of what might happen if it turns out that he isn’t the only one who knows how to do it right. After all, isn’t that the very fear that lies at the heart of the artistic ass-covering practiced by the “classics”? Althamer’s work method practically does away with the concept of plagiarism.

A neighborhood paradise

You can’t have your cake and eat it too. You either work “with” someone or “on” someone. The artist assumes multiple roles in parallel. He is at once in the center — directing and initiating events — and on the sidelines: he observes, retreats, gives way to others. If he is the shaman of his own neighborhood tribe, he does not play the role naïvely. As Massimiliano Gioni writes, Althamer knows “perfectly well that the obscure forces to which he has access are not supernatural powers but social pressures and forms of exclusion and control. Althamer is fully aware that as a shaman, or at least as its contemporary equivalent, he holds a crucial position in his community — for it is through him and his work that society speaks its fears and its desires. He realises he has the potential to be a vehicle for other people’s voices, a conduit for them to channel their dreams and hysterias. And he knows that sometimes he can heal, but only if his tribe agrees to work as one.”

Paweł Althamer, Heaven, 2009, photo Jan Smaga

Paweł Althamer, Heaven, 2009, photo Jan Smaga

Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw

Althamer is often portrayed as a spiritual heir to Joseph Beuys and his concept of “Social Sculpture” — art as a force that can shape the world we live in. Beuys sad: “Jeder ein Kunstler.” Everyone is an artist. Althamer adds: “But if we’re all artists, then no one is an artist.” And just as Beuys had a founding legend — according to which the artist was saved by a group of Crimean Tatars — so Althamer’s own story opens with his Grand Tour: his first trip to Africa in 1990, where he met the Dogon people. Yet the artist doesn’t write his own legend. There is hardly any self-mythologising to speak of, although his art does involve his family, neighbours, curators, and the artist himself. Althamer takes advantage of his own position, but he doesn’t live out the role of the superstar, although he certainly could. Nor is he a theoretician. He has no interest in conflict. This always raises the question: what exactly has he swept under the rug?

Paweł Althamer, fountain

Paweł Althamer, fountain

The Sculpture Park in Bródno,

photo: Bartosz Stawiarski

Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw At the opening of the toguna in Bródno, local politicians and art curators stumbled over each other to offer the greatest words of praise. There was cause for celebration: the Sculpture Park, one of the most interesting landmarks on the artistic map of Warsaw as of 2011, was expanding. But they were also excited about the neighbourhood paradise that was forming in Bródno. Sebastian Cichocki from the Museum of Modern Art described it as a “utopia incarnate”. But what exactly is all this excitement about? A few sculptures in a park surrounded by a concrete apartment complex? The fact that there was less vandalism than had been expected? That people were eager to participate in the artist’s projects? This isn’t the utopia that the Constructivists envisioned. It’s no utopia at all. Althamer merely proves that art is just another mode of communication: sometimes more appropriate than others in that it makes room for intuition. But is it also a method of transformation, one symbolised by the colour gold in Althamer and Beuys’ work?

Szwedka

The construction of Yossouf Dara’s toguna took place over the course of two weeks in front of a defunct bakery called “Szwedka”, next to the apartment building at Krasnobrodzka 13, famous for its role in “2000”. Dara was accompanied by a group of helpers led by Daria, his Polish guide, and Jan, a sculptor from Belarus. New people were constantly showing up: curious onlookers, curators, neighbours, and journalists, all directing their questions mainly to Althamer.

The artist was eager to talk about his recent trip to Mali. When photojournalists asked to take pictures, the artist preferred to retreat into the background: the lead role wasn’t his, after all. Although everyone wanted to see him as the author of the project, Althamer made efforts to distance himself from it. “I don’t want to get in the way. I think they’re doing just fine without me”, he said, whittling away at a wooden horse off to the side.

Paweł Althamer, Path, Münster, 2007

Paweł Althamer, Path, Münster, 2007

courtesy of Foksal Gallery Foundation

One of the neighbours finally showed up to voice his doubts about the project. Why were they making an African toguna? Poland has its own culture, after all. Why do they keep calling it art? Althamer patiently explained everything. He responded to accusations of unnecessary exoticism, saying that he feels perfectly at home in Africa, just as he does in Poland. Similarly, upon returning from one trip to Africa, it struck him just how exotic the common Polish apartment complex is. “There are people who will never accept what we offer them. They will always play a different game. Perhaps my fundamental task is to accept their game. I used to find it schizophrenic, but not so much anymore. I think I can do what I want to do while admiring what others do or don’t do. I don’t have to be conflicted”, he explained.

translated by Arthur Barys