The biennale itself isn’t all that large. It’s not one of those events that will have you dashing from one venue to the next, breathless and anxious about missing something. Anyone expecting to attend a grand festival of Art may leave disappointed. The curators have clearly eschewed the concept of the exhibition as a show, and in many instances have even relinquished their own power. Artur Żmijewski and his team — Joanna Warsza and the Russian group Voina — have redefined the biennale format. The event’s slogan, “Forget Fear”, applies as much to the political impact of art — an issue Żmijewski has been vocal about for years — as it does to the art machine, in which all of us are cogs. The curators have decided to ignore certain rules of artistic decorum, which is probably why they have had to overcome a certain amount of institutional friction.

Fear not

7. BERLIN BIENNALE

Curator: Artur Żmijewski in cooperation with Joanna Warsza and Voina group;

Location: KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Akademie der Kunste, Deutschlandhaus, Saint Elisabeth Church; Berlin, runs till 1 July 2012

I don’t really get the sense that I’m viewing an exhibition. The shows are more like descriptions of projects that are going on elsewhere: congresses that have yet to take place, a handful of initiatives being implemented online, and some projects that are grounded in a mental, rather than physical, space. The biennale abandons the concept of the autonomous, complete work of art as the fundamental medium of communication between the artist and the audience. A certain blurring occurs. But then what is the 7th Berlin Biennale? It is an umbrella venue for all sorts of events, projects, and initiatives that combine art and political activism. Some have more in common with the former — others, with the latter. The exhibition on display at KW is a compromise. The art world can’t get by without openings, and sometimes even without champagne (“art of champagne” read the t-shirts worn by waiters at the reception that I managed to crash). But – again – the opening of an exhibition is just an arbitrary date when it’s not the exhibition itself that matters.

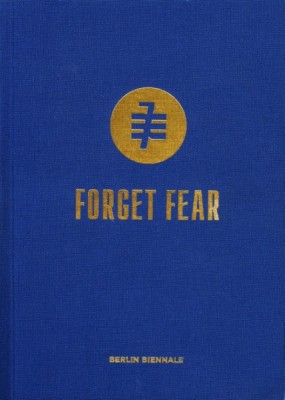

Forget Fear, editors: Joanna Warsza,

Forget Fear, editors: Joanna Warsza,

Artur Żmijewski. Includes conversations

with political leaders, artists, activists

as well as articles by Olafur Eliasson,

Jan Tomasz Gross, Jerzy Hausner,

Joanna Tokarska-Bakir and others.

Berlin Biennale, Berlin, 416 pages, in bookshops

from February 2012Żmijewski and Warsza, as they themselves admit, were driven in their explorations by what they call “news logic”. They followed the buzz. They were interested in learning how a grassroots movement was born in Iceland in the wake of the financial crisis, and how a local comedian founded a new political party, The Best Party. They analysed Hungary’s shift to the right. They sought out manifestations of non-violent ideology. And perhaps the most interesting product of the biennale was the result of this research, the book Forget Fear. A kind of Shivering Bodies 2, but on a global scale (Shivering Bodies is a Political Critique publication comprising of interviews with artists conducted by Artur Żmijewski — ed.). Among the choices made by the curators was to invite representatives of various Occupy movements, who are now occupying the biennale. They’ve pitched tents and posted slogans. There’s a complete radio studio behind the great window just right of the main entrance to KW. Inside, a separate programme from that of the biennale has been posted on the wall. But does it make sense to call it occupation if the occupiers are invited guests? And will they be able to maintain their momentum now that they’ve moved into an art gallery that offers no resistance?

Silence

The surprises started with the press conference. The activists had arranged the space according to the idea that no one is “more equal” among equals. Breaking with the traditional order of such events, the speakers proclaimed their manifestos before attempting to engage the journalists in dialogue, using the gestures employed at Occupy general assemblies. For example, to express approval or disapproval without disrupting the meeting, participants will perform “jazz hands” or “limp wrist” gestures, respectively. Everyone thus agreed that world is mired in crisis and is in dire need of change, but when the leader of the conference posed an open question to journalists about what they could do to change the situation, a silence fell over the crowd. “Preschool”, someone offered.

But I found the silence significant. All you really need to do is to stop hiding your ideology and give up your pretenses of being “objective”. Sometimes you just need to reveal your allegiances. Who’s paying us, and for what? I, for example, traveled to Berlin on the invitation (and dime) of the Adam Mickiewicz Institute. And as the popular adage goes, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. Or, to be exact, no free lazy breakfasts at the Holiday Inn Berlin Mitte.

On the wall of the Occupy camp, someone had written the words “Das Schweigen wird überbewertet” — silence is overrated, a paraphrase of Joseph Beuys’ famous critique of “Duchamp’s silence”. The creator of the ready-made abandoned art for chess, an act that provoked a variety of interpretations. If the journalists and critics (and myself, I admit) responded with silence, it might have been because of the sudden reversal of roles, the feeling of finding oneself in a situation for which one is unprepared. Or maybe we just didn’t have anything to say.

So who gets the Nobel Prize?

Meanwhile, a visit to KW lifts your adrenaline. The whole place is abuzz. The entire upstairs floor is filled with films depicting demonstrations from around the world (“Breaking the News”). The footage is fresh, captured in such locations as Palestine, Hungary, and Poland. The long videos offer a different viewing experience than the short clips seen on television. My attention is drawn to one particularly spectacular stunt by the Kiev-based protest group FEMEN. Stunning Slavic beauties, blond and bare-breasted, shout out slogans from the top of a belfry, ringing church bells to attract attention. “We don’t give birth for you!”, they yell. When the police and security guards show up, the protesters behave in an exceedingly professional manner: they offer passive resistance, assuming the appropriate positions and lifting their fists in defiance. The devushki are then thrown into riot vans.

Key of Return, KW courtyard, photo: Artur Żmijewski

Key of Return, KW courtyard, photo: Artur Żmijewski

But there are also bitter reflections to be made; the facade of KW is graced by an advertisement by the Egyptian telecommunications company that infamously cut its subscribers off from the internet at Mubarak’s behest, curtailing the protesters’ ability to communicate with each other. Today, the very same company employs imagery of the Tahrir Square protesters in their advertisements, accompanied by the words of Austrian president Heinz Fischer, who described the activists as worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize. Apparently the company feels it deserves at least a little bit of the credit.

Propriety works in mysterious ways. But will a corporation step up to make an advertisement out of the enormous key sculpted by Palestinians forced to flee their homes? And from the point of view of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Althamer sending golden people to Brussels in a golden airplane is one thing, but his making gold the colour of a political awakening in Belarus is another.

The Colossus of Świebodzin

Nothing but the head remains of the giant Jesus of Świebodzin, who can be seen looming over the horizon from the Warsaw–Berlin express train. The head, to be precise, is still a work in progress. Mirosław Patecki has moved his entire workshop to KW. Next to a model of Świebodzin’s statue of Christ the King, a Styrofoam copy of the head — also said to be filled with Styrofoam — is being constructed. Patecki had made his way up to the forehead by the time the biennale opened. Next to the sculpture is a film by Anna Baranowska and Luise Schröder depicting the blessing of the giant. The artists captured the people gathered for the celebration, the market stalls, and the whole folklore of the event, while carefully omitting the statue itself.

Construction of Christ the King in Świebodzin, photo: Tomasz Stafiniak

Construction of Christ the King in Świebodzin, photo: Tomasz Stafiniak

Inviting the sculptor/craftsman was an ambiguous gesture. On the one hand, the curators have subjectified an artist from the bottom rung of the operation, a mere contractor. On the other hand, the true artist behind the giant statue is the pastor of the local parish in Świebodzin, undoubtedly a true believer in the propagandistic power of art.

The fact that Paweł Althamer’s “Draftsmen’s Congress” takes place in a desacralised church is not without significance. Professional draftsmen — as well as the general public — are invited to draw something on the white plywood-covered walls and floors of the building. There’s plenty of space to vent your creative energies. Everything is taken very seriously in this venue: anyone who starts drawing is immediately approached by an assistant and asked to sign a copyright release form for their work. The mere idea that my doodles could be copyrighted left me feeling subjectified.

Surrounding the entrance of the church, a deft hand has drawn an enormous vagina. As you enter the church for the first time, you make an unconscious return “to the womb”. But is it the womb of a mother, or the womb of the church? Looking out from within the vagina, you see fresh spring foliage in bloom. There’s a certain solemnity to this debauchery.

Do it in Berlin

Joanna Rajkowska offers visitors another act of birth, this time a naturalistic one in 1:1 scale. Her film is being screened in the underground level of the Akademie der Künste. The scenes depicted in the piece are rather private: the joy of pregnancy, birth, and the presence of her newborn child. Perhaps this is why the film is somewhat uncomfortable to watch. Not to mention the images of pain, screaming, the dripping blood, and the burial of the afterbirth in the Reichstag lawn (why?!).

Still from Born in Berlin (2012), Joanna Rajkowska and Andrew Dixon

Still from Born in Berlin (2012), Joanna Rajkowska and Andrew Dixon

Rajkowska’s daughter Rosa was born in Berlin, a deliberate choice on the part of the artist. Berlin is a unique city, full of contradictions and a indelible history. “Rosa is my answer to Berlin,” Rajkowska writes. Several months after the girl’s birth, Polish doctors diagnosed her with a rare form of cancer afflicting both eyes. A benefit auction of Rajkowska’s work was held in Warsaw to raise money for Rosa’s expensive and complicated treatment.

I believe that a similar rationale underlies the choice of Berlin as the location of the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland Congress, as well as the New World Summit — a conference of organisations placed on lists of international terrorist groups. The same is probably true of the Berlin Biennale itself.

In defense of lost causes

At KW, I pledge never to use drugs, a pact I seal with my own blood from a pricked finger. Considering the fact that I haven’t smoked a joint since high school, much less consumed anything harder, and that I quit smoking a few years back and don’t even eat potato chips, there’s nothing at stake in the promise. Just a quick prick of my finger.

PM 2010, Teresa Margolles, photo: Marta Górnicka

PM 2010, Teresa Margolles, photo: Marta Górnicka

Drug consumers in Europe and America drive the narcotics trade in Mexico and South America. The drug wars on the US–Mexican border have left hundreds dead. Teresa Margolles has wallpapered an entire wall with covers of a glossy magazine published in a Mexican border town. The images are pin-up style photos of the bodies of murdered women. Former Bogota mayor Antanas Mockus, a politician known for his unconventional ideas, is taking a stand against the killings by collecting blood pledges. He has stated that if the project doesn’t succeed, he will consider himself a failed artist and art itself pointless. I wouldn’t be too optimistic.

Erika Steinbach’s grandfather’s wagon

Her grandfather planted turnips in his garden, but he never got around to harvesting them, forced to flee from the approaching Red Army. But he did take along a cardboard suitcase, some papers, and a few belongings in a little wooden wagon. Now these salvaged objects — family souvenirs from places long abandoned — are on display at Deutschlandhaus, a building/palimpsest soaked in the ideologies of the German state’s many incarnations, soon to become the headquarters of Stiftung Flucht, Vertreibung, Versöhnung. Invited to participate in the biennale, the foundation assembled an ad hoc exhibition of family memorabilia. Full of old attic junk, the exposition resembles, at first glance, a cross between an anthropology museum and a Holocaust museum. Each object contains the story of a particular family, a personal tragedy.

Berlin-Birkenau, Łukasz Surowiec, photo: Marta Górnicka

Berlin-Birkenau, Łukasz Surowiec, photo: Marta Górnicka

The exhibition sets aside revisionism and issues of responsibility for World War II. At what point does personal history become political? When does it become an international problem? And when does an exhibition turn into a scandal, as a few government officials probably feared? The biennale is, after all, partially funded by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute.

Birch saplings from Auschwitz followed the expellees to Berlin. The trees were brought and planted at various locations throughout the city by Łukasz Surowiec. An attempt at demystification, or a pang of guilt? Did your grandpa serve in the Wehrmacht, too? Every German, and even every Pole and every Russian, can take a sapling home and look after it like a tamagotchi.

After the birch trees came historical reenactors from Poland to recreate the Battle of Berlin on the first Sunday of the month, a sin they’ll confess come first Friday. Poles playing Germans, the Red Army, and Anders’ Army. But they’re shooting themselves in the foot: what’s there to reenact once Berlin’s been captured? They’ll capture Berlin in Warsaw. The Centre for Contemporary Art will serve as Hitler’s secret bunker.

What next?

The 7th Berlin Biennale certainly won’t convince anyone of the political impact of art. “Everything has already been done,” after all. There’s no point in preaching to the choir. And yet the curator has made inroads. How deep they go still remains to be seen.

Battle of Berlin ’45, photo: Maciej Milecki

Battle of Berlin ’45, photo: Maciej Milecki

Żmijewski has set a clear course. He has identified a place where art abandons its autonomy or exploits it: such is the rationale behind the symbolic gesture of taking on as curators the anarchist anti-Putinites in Voina. In terms of the biennale, these are no longer the sidelines we’re talking about. This is the very heart of the change. Everywhere I went, I heard opinions about how the next biennale, the one in two years, will once again be about art. Perhaps even reactively so. How permanent will 7BB’s influence on the so-called art world be? I’m reminded of what Tracey Emin once wrote about getting her driver’s license: “I’m so worried I’m going to fail. Everyone else is worried I’m going to pass.” The biennale is like driving with no hands. I’m concerned that the art world might just bury the idea of “political impact” out of its fear of having Żmijewski in the driver’s seat.

translated by Arthur Barys