Run by artist Grzegorz Klaman and curator Aneta Szyłak, the Wyspa Institute of Art at the Gdańsk Shipyard appears to have changed very little in the many years since its inception. The walls remain unpainted and coldly post-industrial. The single addition since my last visit (I’d be dating myself if I were to admit how long it’s been) is a club called Buffet, located on the ground floor.

The shipyard is collapsing in on itself, even though the enormous home of the future European Solidarity Centre is being built just across from the Monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers of 1970, and Lenin’s name was recently reinstated over the main entrance. The communist revolutionary was the shipyard’s original namesake. The reconstructed gate is a replica of the one seen in footage of the historic events of 1980. But not everyone has taken kindly to this quotation from the past. In a bold move, Lenin’s name has been covered by the Solidarity logo and a fluttering white and red flag.

Alternativa 2012

Gdańsk Shipyard; open till 30 September 2012. Exhibitions:

Now is Now, Wyspa Institute of Art, curators: Dominik Kuryłek, Anna Ptak, Ewa Małgorzata Tatar;

Materiality, Hall 90B, curators: Arne Hendriks, Inês Moreira, Aneta Szyłak, Leire Vergara

The Solidarity Shipyard in Gdansk isn’t just another factory that’s become a home to artistic endeavors. The artists behind Wyspa are constantly challenged to live up to the context they’ve inherited. Wyspa is like a bracket fungus, a growth on this gigantic yet partially necrotic body. Whatever the subject of their next exhibition, the shipyard will always play a supporting role.

The Island

The 2010-2012 series of exhibitions titled Alternativa is no exception. The project has just entered its final phase. This year’s edition comprises two exhibitions, Materiality, on display in Hall 90B, and Now is Now, at the Wyspa Institute of Art.

Wyspa’s roots go back to the 1980s. Grzegorz Klaman, who arrived in the Tri-City area during Martial Law, recalls how he had hoped to encounter cultural processes that mirrored the political turmoil of the time. Meanwhile, he himself was forced to become a leader of the independent art scene in Gdańsk. Along with other artists such as Kazimierz Kowalczyk, Klaman created works of land art and launched a series of events in venues he scouted out himself.

The abandoned and crumbling Granary Island on the Motława river, just outside Gdańsk’s Old Town, was especially attractive to young artists, and several outdoor events were held there. The student gallery run by Klaman and a group of his friends was also named Wyspa (the island).

Like a hiccup

The curator trio behind the WIA’s exhibition about these pioneering days, Now is Now, borrowed the title from a two-day show held at Granary Island in 1988. Their choice reflects the contemporaneity of the institution that grew out of those experiences and Klaman and Szyłak’s work in the 90s (Open Atelier, Łaźnia). On the other hand, this emphasis of the contemporary is intended as a reflexion on the phenomenon that is the archive and the inaccessibility of the experience it conveys. Where does all of this take us?

There are hardly any works of art in this rather sizable exhibition. You can make out a pair of sculptures from the period in the dark hall, along with a handful of drawings, but the bulk of the space is dedicated to archival material arranged in square, glass exhibit cases that resemble large drawers, all thoroughly labeled with an abundance of text by the curators.

The exhibition appears interesting at first sight, but is revealed to be somewhat incoherent upon further inspection. I’m willing to bet that its creators had more fun putting this multi-storied structure together than I did trying to unravel it. It comprises photographs, slides, documents, fliers and catalogs, all sorted into four categories: work, places, encounters and myths. Work, because the artists executed large-scale, labour-intensive outdoor compositions. Places, because their work was consciously done in specific contexts, as demonstrated in Klaman’s manifesto, titled Archeologia odwrotna (Reverse Archeology). And encounters, because their art served as a social glue within and above their own milieu.

Myth

There remains the myth. This isn’t Wyspa’s first foray into automythology; the institute recently hosted a Klaman retrospective. The curators of the current show appear to be taking a critical stance toward that mythologisation, but fail to assume that same critical attitude toward their own work. I’d be willing to overlook these shortcomings, if only out of respect for Klaman and Szyłak’s oeuvre, if it weren’t for part two of this exhibition.

Not satisfied with merely putting the archive on display, the curators have also chosen to elaborate on all the obstacles they had to overcome in doing so. Among the revelatory conclusions they reach is, for instance, the statement that archival images and footage fail to convey the immediacy of the direct encounter with art. Eureka!

Now is Now exhibition view, photo: KS

Now is Now exhibition view, photo: KS

To prove their claim, the curators have taken images from the catalogue of the original 1988 Now is Now show and created flat, black contour models. What was once three dimensional is now filtered through a two dimensional photograph to become a flat and distorted perspective shortcut, like a photogram or shadow. I stared in disbelief as I made my way around this installation, which occupies an entire floor.

I’d rather the curators made an attempt to overcome their impotence rather than emphasise it.

The workshop

Fortunately, no such slip-ups can be found at the Materiality exhibition in Hall 90B, the main part of Alternativa 2012. The two shows do share a few common themes however, while the shipyard inevitable serves as a common denominator – the shipyard seen in Adam and Anna Witkowskis’ film The Past, in which the couple watch as plant life engulfs the enormous factory (on display at Now is Now as a quote from the 2005 exhibition Dock Guards), and the same shipyard photographed by Michał Szlaga, who, day after day, observes and documents the plant’s gradual collapse (on display at Materiality). And a glance out the window reveals a crumbling landscape in which materiality finds its ultimate representation.

It’s as if all life has abandoned the giant, defunct factory hall. Not just because of the empty warehouses and the fact that it’s been years since anything was actually manufactured here; at times, it’s the exhibition itself that seems devoid of life. At the time of my visit, the mini-factory designed by Sjef Hendrickx to produce paper bricks out of documents wasn’t operating.

Materiality, photo: 8485, Wyspa Institute of Art

Materiality, photo: 8485, Wyspa Institute of Art

In a corner, the group Partizan Publik set up a Gastev workshop. At the behest of Lenin, engineer/artist Alexei Gastev created a machine that would transform farmers into workers. To operate tools and machines, they needed to acquire new knowledge and muscle memory. The revolution needed a new type of person. The phenomenon of the human/machine is alluded to in another reconstruction, a 1960s dance performance titled The Dance of the Machines.

The new shipyard gate is also more than merely an attempt to produce a simulacrum of the past, one efficiently disarmed by disgruntled shipbuilders: it is an expression of nostalgia about a time when labour was labour, and progress was synonymous with pushing the industrial revolution forward.

Circulation of matter

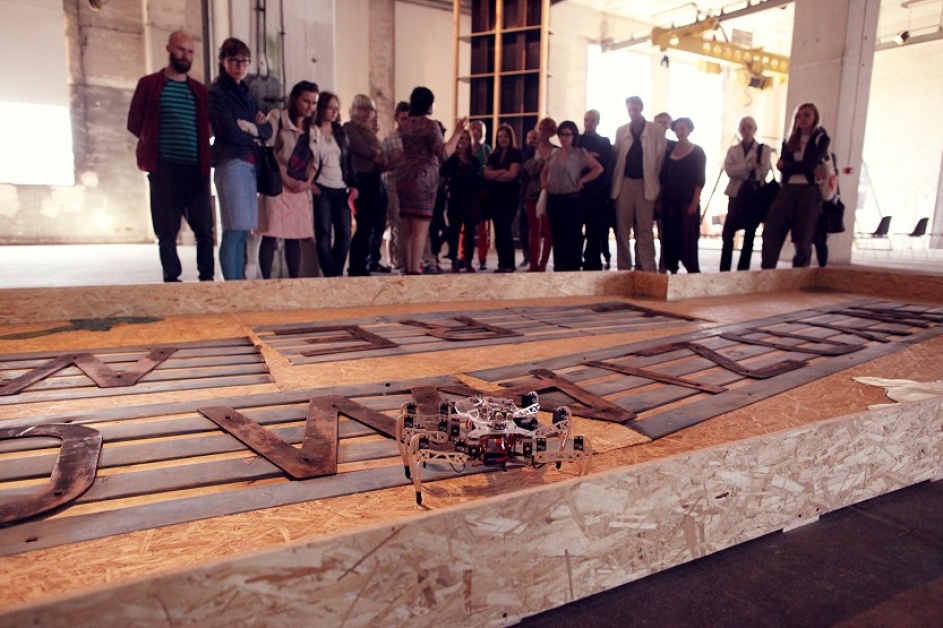

A robot spider crawls over the original sign that hung over the Machine Repair Plant, now laid flat. The mechanical creature appears to be observing its surroundings carefully. There are a few organic blotches here and there – bioactive material “grown from fungus cultures found on the grounds of the former shipyard and human DNA.” Grzegorz Klaman’s The Machines Return to the Factories appears to pose questions about the local and contemporary context. The changes are irreversible. The shipyard machines need more than just repairs. And the future lurks around the corner.

Materiality, photo: 8485, Wyspa Institute of Art

Materiality, photo: 8485, Wyspa Institute of Art

Meanwhile, accepting the destruction of the artists’ work, claims Klaman, was among the main activities that went on at Granary Island in the 80s. But destruction doesn’t spell the end of the world. It is believed that every single carbon atom takes part in some life process every 200 years, on average.

Global (and local) recycling represents an attempt at finding an answer. Shipyard documents can be processed (Hendrickx); mines, bombs and missiles can be disposed of, like the main character in Hiwa K’s film Nazhad; and surplus airplanes can be repurposed in any number of ways. Some are broken down to make DVDs, while others, ironically enough, are destroyed in spectacular explosions on the sets of action films. A film by Hito Steyerl explores these very themes. Industry, in this case, is inextricably linked to spectacle.

As Steyerl demonstrates, recycling escapes the logic behind the circulation of atoms: there’s also the logic of the spectacle. In nature, nothing is lost. A film by Sally Gutierrez depicts a form of cruel recycling that is the organ trade. And, finally, a former warehouse can be reused as an exhibition space.

Other objects

The exhibitions is full of objects of all sorts. In a 45 minute video, Inaki Garmendia examines the various parts of an S.T. Orbea racing bike. Martí Guixé hires a bondage expert who, using a series of complicated knots, horizontally suspends two Tizio lamps designed by Richard Sapper. These are name brand objects.

Materiality, photo: 8485, Wyspa Institute of Art

Materiality, photo: 8485, Wyspa Institute of Art

Mateusz Herczka designs new tools and new applications for them: his parasitic chapel is intended to enable a human to marry a building. The artist doesn’t explain why anyone would want to do so, but the prospect remains enticing, regardless. The project is the polar opposite of the story of Cuban work brigades that built their own prefabricated housing complex, which they then moved into.

The whole exhibition is reflected in a row mirrors set up by Lex Pott. The artist has accelerated their oxidation, leaving them neither new nor old.

Stagnation

Materiality explores many themes concurrently: labour and architecture, recycling and design, humans and objects. Atoms circulate through the universe, though not always at a speed that we would find satisfying.

The Islanders’ have the rare gift of blending their own local reality with global processes. Alongside international artists, the exhibition features a rather robust roster of local talent, from Grzegorz Klaman to Mariusz Waras and Katarzyna Józefowicz.

As you pass by Gdańsk’s famous port crane, it is apparent that for several decades, little has changed across the river on Granary Island: a billboard has been set up, advertising a low-cost airline that makes Gdańsk feel closer than ever. With its cracked walls and overgrown concrete, the shipyard is stuck somewhere between the Industrial Revolution and the post-industrial era, whatever the sign above the front gate happens to say at the moment.

translated by Arthur Barys