ADAM MAZUR: How did you become a curator at the Berlin Biennale?

ARTUR ŻMIJEWSKI: An advisory body organises a sort of closed competition with candidate submissions. I was invited to participate in that competition, so I wrote up a project which eventually got picked up.

What did you end up submitting?

I wanted art to start giving people answers. Instead of incessantly asking questions, we identify the problem and the artists propose possible solutions. I also proposed that artists participating in the Biennale should be very different when it comes to opinions and outlook. So we could bring diversity back to art, witness a visible clash of rationales. People other than artists should also be allowed to participate in the Biennale. I wanted to avoid a situation, where we once again host a meeting for the high and mighty of the art world, who motivated by good intentions want to change the world for the better, and usually end up doing nothing. I wanted the Biennale to be a place where we react to what goes in our reality, where we find solution to the problems of today. Without the artistic reaction being delayed for months or even years.

I understand that this outlook was borne out of your previous Biennale experiences, as well as your artistic practice and movies like Them?

The 6th Biennale – the most recent one – was very noble and admirable. And that’s all good, but that kind of exhibition does not really do anything to change even people like us – by which I mean the artists. In one of the issues of Brulion I read that the people behind it are united by a common vision of politics and culture. But among these people we’ll find both noble people, and people who are total assholes in private. That declaration revealed some fundamental difference.

Artur Żmijewski

Born in 1966 in Warsaw. Polish visual and conceptual artist, filmmaker, photographer. Graduate of Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. He is an author of short video films and photography exhibitions. In 2006 Żmijewski represented Poland at the 51. Art Biennale in Venice. Regular collaborator of the Foksal Gallery Foundation. Since 2006 he is the artistic editor of Krytyka Polityczna, the magazine.

I wanted Biennale to include people whose motivations are borne out of, e.g. violent experiences, distance towards the other, religious fanaticism, resentment, I wanted people who are firm believers in capitalism, etc. The art world is dominated by a humanist outlook with an extensive centre-left spirit. And I’m interested in violent differences of ideas, because that’s the foundation of politics. If we expose the differences, then there’s room to operate, whereas if we’re dealing with all noble and kind-hearted people then the situation turns stagnant and still.

Your statements carry a clear anti-establishment mark, you often express anger towards the world of modern art and towards the “ideology of the art world”.

Art, trying to pass itself off as going against the system, resisting the power structure and the economic structure, is a closed system in itself. The players of the art world, while criticising the violence of capitalism, foster economic violence in their own field. Only a few prominent artists have access to profits flowing from the art world, while the artistic proletariat hovers near the poverty line. I think that this is one of the reasons behind art’s ineffectiveness. This is art’s inner lie. I believe in its intrinsic possibilities – art is an alternative way of experiencing and transforming reality. It offers opportunities to think and act which not even politics or the bureaucratic systems of government could give you. It has this “impossible” inventiveness that enables us to redefine the world. Unfortunately, it’s dominated by an ideology of helplessness, periphery, and ineffectiveness.

How would you define yourself as a curator?

I think the closest term is “moderator”, someone who mediates between conflicting view and doesn’t try to create consensus, but rather wants to create a place where differences can flourish. It can lead to a sort of ideological war, but the baseline is that we start with “a common cause”, the Biennale. But that’s not all there is to it. Being a curator is a brutal job, because you have to disagree with the artists’ initial proposals. I like to foster a vision, where the curator gets together with the artists and they try to solve a problem. Where the curator disagrees with the artists, and vice versa, that there’s a tough game of back-and-forth going on between them.

If I were a curator of the previous Biennales, I think I’d be offended by your statements about the curators’ limited imagination, the aestheticisation and their tendency to avoid the big issues. Are you speaking as an artist-experimenter, a radical who is able to shake the foundations of the petrified, cloistered art world and propose something new?

When talking about limited imagination, I’m talking about my own imagination too. And I wasn’t saying it to offend anyone, but rather to point out the limits of art. The imagination of artists and curators traces the limits of art. I’m not interested in novelty or originality, and I’m not going to yield to the dictate of these categories. I also wouldn’t like to be labeled a “radical”. Many people in the art world, including curators, exhibit radically conservative views.

You don’t want to “radically” oppose that?

I’d like to avoid a situation, where you represent the moderate centre, while I’m the radical who wants to demolish a well-constructed reality. I’d rather say that you represent the institutional status quo that wants to reproduce culture in its current shape, along with the ideology of helplessness that permeates it. And I’d like to speak for people who want ideas to dominate over procedure, who want culture to dictate policy, and who posit that art should be able to quickly react to events taking place around the world.

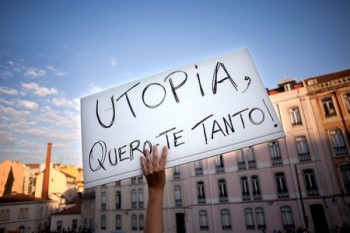

Occupy Berlin, Berlin, November 2011

Occupy Berlin, Berlin, November 2011

photo: Sandra Teitge, 7. Berlin Biennale blog

Maybe you postulate these kinds of things, because as an outsider, you can allow yourself to be fearless in your artistic work?

I’m not an outsider. Placing me outside the system enables people to think that “he’s an outsider, unconstrained by the same obligations, he can do what he wants. He’s working with miracles, so even if today everything is blank and bland, tomorrow Żmijewski’s gonna drop by and conjure up a whole new reality for us.” Meanwhile, I’m in the exact same place as you are, the same place as Kathrin Rhomberg, the curator of the previous Biennale. What distinguishes me is the fact that I’m not playing for keeps, I’m not looking to be hired as a curator again.

Can we consider your Biennale a work of art?

That’s a wrong way to go about it.

How do you perceive the Biennale then?

It’s still a mystery to me. There’s a lot of unclear relationships, institutional dependencies, and games in that world. From all the decisions a curator can make, letting go is still the most desired one, because it fits the institution’s logic the best. I spent over a year talking, convicing, fighting fears both mine and other people’s. And fighting this ideologic coercion, demanding that artists keep away from the political fire and not think about the permanent effects of artistic action.

How did you end up in that position?

Miracle logic is one of the reasons. Picking me was on one hand supposed to support the notion, that in the world we can just “flip a switch” and save the world and that we can forget the systemic limitations that we helped create. On the other hand, this choice was motivated by a desire to hire someone with no intention of curating again, someone who might just take a shot at and try to truly change something in the art world. The only problem is that I’m also a node in the institutional web of fears, fears of losing your position in the field, a part of the battle to keep your influence and the present power structure intact – and all of this weakens the force of the artists’ expression, it softens and diffuses the language we use. The logic of institutions dictates that politics be appropriated and limited to exclusive cabinet meetings. Artists are left with worthless pseudo-political spectacle. The institutions’ reaction to a given subject is an excellent barometer of its importance and timeliness. And allow me unjustly radicalise this opinion by stating that you can recognise the most important subjects by the fact that cultural institutions won’t touch them.

You said you’re not playing the curating game for keeps. What is it that you do want?

I want to find the answer to one particular question: “Where and how does art truly make a diffence?” Where does the truth of artistic action really lie? And by truth, I mean that things happen, the reality is formatted, while the artists and other participants suffer the consequences? Is there even art that really works? Let’s try to find just a few artists, who actually take part in some unceasing transformation of reality. We’re imprinted with the notion that art dabbling in transformation always results in the rise of totalitarianism or some other ideological dictatorship. And as we know, there’s dozens of artists who decided to engage in transformative art and ended up dictators, right?

I see it this way: reality is constantly in flux. We’re constantly facing new challenges. There’s 7 billion people living on Earth. Why do some countries have overabundant food supplies, while others starve? How do we deal with the fact that we made a business out of charity and humanitarian help? With colonialism still thriving in Europe? With the total loss of trust in the political process? How can we help these few billion people to decide their own fates? So they could have access to education and healthcare? What do we do with our ineffective economy? How do we deal with those issues when they rear their head in Poland and Europe?

Why do you think that art has any answer to these questions you mentioned? Wouldn’t it be better to just drop art and get yourself involved in social or purely political activism?

The rise in activism and involvement in politics is a very good trend. I don’t have anything against people who join a think tank instead of wasting their time on empty artistic gestures. Doing something that has actual influence on society is great. But I’m talking about equipping art with tools that will enable it to act effectively, and creating new politics through art. For our brainwashed minds, the cynical political spectacle which we’re subjected to every day is completely natural.

When reading the „P/Act for Art” magazine issued for the Biennale, I was under the impression that you were very harsh on Berlin, which is Mecca for many Polish artists. What’s your attitude, as a curator, towards Berlin and Germany?

Berlin is an amazing city: it’s soft, cozy and safe. It’s not about taking out your anger on Berlin – it’s about Berlin’s cultural sector acquiring enough importance that its representatives could enter the city’s authorities, where they could shape Berlin’s cultural policy. When I was making “P/Act for Art” I knew that Berlin’s cultural circles represent various interests and would rather wait for the politicians’ decision than try to force them to realise some of their postulates. So it was more about an important institution – like the Biennale – supporting brave artists who want to speak about their basic problems: social, economic and professional.

Observers and organisers of the Biennale treat it as an international event, which is supposed to highlight Berlin’s position on the cultural map of the world, while you expose complex local problems, tensions, and conflicts.

There’s nothing complex about the fact that in a time of crisis, where cultural institutions don’t have money to carry out their own programmes, the mayor of a city proposes to organise a large exhibition, just a few short months before the start of his reelection campaign, financed by the local authorities and a million euros that he conjured up from a lottery. We’re in the middle of a local news item. It was the talk of the town for weeks.

In your critique of the Berlin scene you talked about the “false depoliticisation of art”, something which you mentioned in your interview with Sławomir Sierakowski. Is authentic politicisation of art its opposite? What would that politicisation entail? By the way, it’s very interesting how invested you seem in categories like “true” and “false”. From what I can gather, you sensed that falseness, that lie, in Berlin?

Berlin isn’t a city of culture because creating that kind of image was necessary to promote the city, but because a certain hope was kindled there. That it is a place where you can enjoy your freedom. And that’s true – Berlin isn’t as suffocating as the Netherlands, where art and culture are mocked by the right-wingers. It’s not like in Budapest, where nationalists get picked as heads of cultural institutions. On the other hand, the Berlin art scene turned away from politics and is now being manipulated by politically savvy players. After an era marked by rising prosperity, artistic success, and increased investments in cultural infrastructure, the Berlin-based artists started realising what role they were assigned in the grand scheme of things. Klaus Biesenbach said that right now Berlin looks a lot like Kassel during Documenta. And there is something to it.

We need to keep fighting, because Berlin is full of artists – and the stakes are high, it’s about how these artists will be “utilised”. Right now, the commercial use concept seems to be winning, and this concept orients the culture industry toward increasing profit. We need to stop that trend, we have to retake our right to decide about our fate. Artists comprise a fairly large group in Berlin – but they’re unaware of their collective power.

What would an authentic politicisation of art look like?

I don’t know, I’m still looking for an answer to that question. That’s the question the Biennale is supposed to ask: “If art were to act truly politically, what would this action be like?”

Is not finding an answer, or failure, even an option for you?

I can already see that the answer’s out there. We’ll have to see whether it’s satisfactory. The problem lies in alienating that answer.

You once mentioned that Yael Bartana’s trilogy didn’t dig deeper, past the aesthetic level. You also criticised the previous Biennales for over excessive aestheticisation of art’s political potential. Did your attitude towards the issue change due to the fact that you’re a curator at the Biennale now and you invited Bartana and her Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland to participate in the event?

Excessive aestheticisation results in spectacle, instead of giving you a real, measurable effect. Yael’s intent was that by starting with a movie she begins the process of self-education, looking for a political objective, looking for substance for her idea, which would then turn into a collective motivated by a common idea. The idea morphed into a common goal and work towards reaching of that particular objective. We can escape aestheticisation by finding something that unites everyone: people have to be playing for the same stakes. That’s what the congress is for. And we’ll see what will be the visible effect of that process. Art can turn a political idea into worthless spectacle, an empty gesture. The logic of turning ideas into spectacle is a trap also in this Biennale, and I don’t think any of us – meaning Joanna Warsza, Wojna, and I [“Wojna” is the acronym formed by the names/aliases of Żmijewski’s collaborators – Oleg Worotnikow, Natalia Sokol, Kacper Nienagliadnyj Soko, Lonia Jebnięty – ed.] – will be able to escape it.

Occupy Wall Street, New York, October 2011

Occupy Wall Street, New York, October 2011

photo: Peter Snadik, 7. Berlin Biennale blog

The fact that you, an artist, are a curator at the Biennale is unique in itself, you can’t escape that, can you?

Neither the fact is unique, nor am I. Another artist – Maurizio Cattelan – has already been employed at as a curator at an earlier Berlin Biennale. I just want to direct the artistic action that will take place during the Biennale to achieve certain effects, e.g. I want the Political Critique club in Berlin, established as part of one the Biennale’s project, to exist and flourish after the exhibition ends, I want the leftist international to keep forming. I want to do as much as I can with this tool that has been given to me for a period of time.

Are you planning to work on critics and criticism itself?

We wrote down a few conversations that Joanna Warsza and I had with a number of people – we worked to distill it into book form which we could release for the Biennale. That was supposed to be a process of convincing ourselves that art could be really pragmatic. A wide selection of these texts will be published in Polish in the next issue of The Political Critique. The idea was simple, and I hope shared by many people – I want art to manipulate reality. And I’m not using “manipulate” in a negative sense, I just want it to be a basis for effective action. I don’t want people to think that art is “useless”, that artists have some freedoms that others don’t enjoy. And if they do, they can be used for achieving pragmatic objectives.

One of your significant successes is joining The Political Critique, which published the Applied Social Sciences manifesto, but you haven’t yet had a project, where you expected people to rise up and join, one which the people would treat like a sort of call to arms? Like, for example, Bartana, who founded the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland.

I didn’t build any social movements which would be founded on artistic action. I have, however, tried to understand what I am part of. That working with The Political Critique to open the world of politics to average people, especially in the case of decision making, to democratise the government, and to politicise culture. Culture and art cover a significant part of the public opinion, therefore it’s a method of putting pressure on those in power using the means available in a democracy – symbolic ones.

Anti-G20, Toronto

Anti-G20, Toronto

photo: Eduardo Lima, 7. Berlin Biennale blog

That’s why Bartana’s work is unique to me, while your actions don’t really result in works of art, your work is institutional and allows others to assimilate ideas and calls to action via the Biennale.

Bartana’s work might be unique, if she only manages to find some ideological glue to bring people together, and if she decides to be the leader of this undertaking. If Jewishness will become a political idea for the movement, instead of a collection of religious rules. It might be an idea of a minority retaining its autonomy, or a batch of social ideas proposed by a minority operating in very hostile conditions – of exclusion, isolation.

We don’t commission artworks from Biennale artists – we commission them to come up with solutions to social or political problems. In the end we’ll perceive them all as works of art, because that limited conceptual framework is all we have to work with right now.

You’re planning some Biennale-related events in Poland, there’s going to be a companion exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

Working on the Biennale would have much less sense if its effects were to be limited only to Berlin. We need to transplant them here. The Museum of Modern Art, in its own way and through its own research is trying to find the answers to questions we pose in the Biennale. Both here and in Berlin, we need to find the answer to one question: “where does our art really belong?” For example, I’m reading Gazeta Wyborcza [biggest Polish daily - ed.] and the headlines are all politics-related: “Qaddafi dead”, “Greece is bankrupt”, “Kaczyński on the defensive”. Then I reach the culture section and I can see that everything past these political headlines is confined to some dusty borderland of reality. The world is in upheaval – people create pan-European social movements, people are occupying New York, wars are ending, capitalism is going bankrupt, not just morally, right in front of our eyes, while culture is still dominated by this “art is useless” outlook.

Has working on the Biennale changed the way you think about art?

Experiencing such an awesome institution from the inside is amazing. I saw, and familiarised myself with, the constraints present within art itself, stemming from e.g. the fact that the institution and the artists keep playing for different stakes, that procedures are often more important than ideas. The institution wants to survive in a system marked by changing governments, uncertain financing, and multiple entities fighting for the same money. When I sign on as curator, my artistic freedom and freedom of ideas goes on hold, because the only thing the artistic director listens to is numbers. I can still choose, but my job as a curator involves mostly talking – I’m incessantly trying to convince people to see things my way, and trying to win people over.

All this energy that artists put into draping the paradoxes in substance or matter really tires me out. I know that this energy is lost on constructing that paradox. And that this paradox, now in the form of an artwork, will be used deliberately in a way that will make the audience try in vain to solve its riddle.

So we need to transgress the boundaries of modern art?

I think there’s a treasure deep within art itself. I think that art is the enemy of that terrible ideologic cynicism that’s spreading like wildfire through the entire world, through institutions of the state, and the world of politics. I don’t know whether we should transgress the borders of modern art, because I feel that we’ve done this multiple times already. I think we should rather be more pragmatic. If pragmatism were to replace the production of these “intellectually astonishing” paradoxes, then I’d say that one of art’s limitations has been demolished. We’re hearing in the news that the stock exchanges are being run by people who are addicted to risk, and can see with our own eyes that capitalism produces people addicted to certain lifestyles. Striving after satisfaction through experiencing paradoxes and questions without answers that the art world produces is also a kind of addiction. This entire field resembles a kind of anthropological chaos: a vortex of formal inventions, not quite sociological, unfinished analyses, a mixture of visual languages, grammars, requests for breaking taboos, some subversive practices, participation, group conformity, traditionalism, etc. That doesn’t satisfy me at all.

Warszawa, 1 November, 2011

translated by Jan Szelągiewicz