AGNIESZKA SOWIŃSKA: You recently wrote on your blog that “books, as stupid as this might sound, should have paper, a cover, and should be read in peace and quiet. Every work of art, be it The Magic Mountain or a comic book about Batman, or a Master’s Hammer album, has encoded in it a certain way in which it is intended to be experienced. And that’s something we should respect.”

ŁUKASZ ORBITOWSKI: I stand by those words, of course, and I’ll try to explain what I meant in a second, but I think that we’ve started taking the words of writers too seriously?

You mean we treat them as engraved in stone?

Exactly. And yet when I write something on my blog (in Polish — ed.), I’m influenced by the moment. I sometimes try to make too great of an impression with my blog posts. Or I could be sad, or trying to infuriate someone, or I could be hungover, or I could have just gotten some crazy idea in my head that I can’t shake, even though there’s this voice in the back of my head telling me to snap out of it. Even now, as I’m talking to you, I’m trying to be funny and impressive and I’m exaggerating some of my opinions.

Łukasz Orbitowski

Łukasz Orbitowski, born 1977, is a writer and journalist. He is the author of the books Tracę ciepło (I’m Losing Warmth), Horror show!, Święty Wrocław (Holy Wrocław), Nadchodzi (It’s Coming), and Prezes i Kreska. Jak koty tłumaczą sobie świat (Kreska and the President: How Cats Explain the World).

The winner of numerous awards and scholarships, Orbitowski spent his colourful college years mired in Kraków’s night life and the black market. He once built houses and drove a snowplow in Boston, but has since focused his attention on his literary-conceptual work. Now well into his thirties, he is the father of one straw-blond son, Julian. He is a cinema and video game lover torn between the gym and the bar.

He writes for the Polish magazines Przekrój and Nowa Fantastyka, and describes himself as either “the Luke Skywalker of Polish fantasy” or a “cheerful hothead”.

He currently lives in Copenhagen.

But when I’m practicing the “alchemy of the word” (a quote from Jan Parandowski — ed.), there’s something within me, within the core of my existence that produces feedback and focuses in a manner that is completely unachievable in any other situation. Sitting here talking to you, I can’t come up with the ideas or ways of expressing them that (I hope) I manage to produce when I write. It’s like with the Ouija board: I sit down to write and my hands suddenly start tapping at the keyboard all by themselves. But that wasn’t your question.

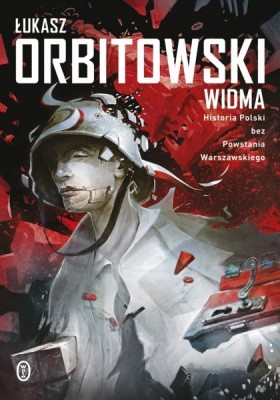

Right. I asked you about the ways of experiencing works of art encoded within them. For instance, how exactly are we supposed to read your book Widma (Phantoms)?

Piously (laughs). I like to imagine my readers sitting down to that book in peace and quiet. The format itself calls for…

Exactly. Who has time to read a 644 page book these days? It’s a bit too heavy to carry around in your purse.

Who says you can’t sit down on the couch, put your feet up on an ottoman, open up a bottle of wine (just one — I don’t want to give my readers the wrong idea) and sip it along to some music while reading a book? I think we need to organise our everyday lives in a way that gives us time to read in peace. I don’t think we should be applying to literature the ways of experiencing culture that we’ve learned from the internet and music videos.

But can the two be kept separate? Hasn’t our perception already been shaped by the internet and music videos?

I at least try to keep the two apart. Books have something to give us, they have whole worlds of potential that we just won’t perceive if we read them on our computers where they share our attention with gossip sites, twitter and funny videos. That’s not what it’s about. Although that is one way of reading.

Perhaps the prolonged concentration that books require of us is a thing of the past?

Is there any point in fighting for love in a world of pornography? There might not be, but we try anyway. I’m enthusiastic about the internet, I like watching videos, and I enjoy fast culture. I don’t want the message of this interview to be that books are important and music videos are dumb. I love playing first person shooters on my gaming console, and sure, I love watching a good blockbuster. But that’s not all there is. There’s a time for one thing and a time for another. Winning someone’s heart is one thing, and a back alley quickie at the dance is another. The former gives you more satisfaction. Not that back alley quickies don’t have a certain charm; by no means am I questioning the significance of the back alley quickie. But if that’s all there is in your life, it’s not going to be a good one.

Winning someone’s heart takes time, hard work and attention.

But isn’t life about more than just pleasure and relaxation? I get a bit worried when I hear someone say “that’s a great book, you just can’t put it down”, or “that was a great movie, I felt really relaxed”. I understand that, and I know that that’s important. And I find myself gravitating towards such uncomplicated entertainment at times. But there’s no way to comprehend complex worlds without some effort.

With all the different kinds of narratives available to us today, books are seeing a lot of competition.

But notice how younger media aspire to the status of books. Once the comic book had matured as a genre, by which I mean it became more than just a bunch of stories about guys who wear pants on top of their trousers, the term “graphic novel” was immediately coined. The popular game “Alan Wake”, recently released on PC, is divided into chapters and the character is the writer, while the box edition, which I have at home, includes a novel. The entire game takes the form of a novel. Modern TV shows have become the equivalent of serialised fiction. That’s Jacek Dukaj’s observation, I’m only repeating it here. Areas abandoned by novelists have been recolonised by artists in the field of film and television. But the book is still the medium that is most open to the imaginations of others. It’s irreplaceable.

But notice how younger media aspire to the status of books. Once the comic book had matured as a genre, by which I mean it became more than just a bunch of stories about guys who wear pants on top of their trousers, the term “graphic novel” was immediately coined. The popular game “Alan Wake”, recently released on PC, is divided into chapters and the character is the writer, while the box edition, which I have at home, includes a novel. The entire game takes the form of a novel. Modern TV shows have become the equivalent of serialised fiction. That’s Jacek Dukaj’s observation, I’m only repeating it here. Areas abandoned by novelists have been recolonised by artists in the field of film and television. But the book is still the medium that is most open to the imaginations of others. It’s irreplaceable.

You moved to Denmark last year in December. What does an émigré writer like to read?

I’ve taken a great interest in Iwaszkiewicz recently. Iwaszkiewicz also lived in Denmark. He moved here for a year or two back in the 30s, developed a fondness of the country, and maintained strong ties to Denmark for most of his life. Before I left I bought his book Gniazdo łabędzi. Szkice z Danii (Swan’s Nest. Sketches on Denmark). I believe that’s the title. Inevitably, I began to feel the urge to explore other books, not just one novels and short stories by Iwaszkiewicz himself, but also the damn Danish writing he had read. Martin Hansen’s The Liar is one example, a bit of hackneyed writing from the 50s, and yet there’s something beautiful about it. Plenty of Danish titles came out in Poland in the communist era thanks to Wydawnictwo Poznańskie (publishing house — ed.).

Iwaszkiewicz isn’t very widely read these days, if you don’t count his recently published Dzienniki (Journals).

I completely don’t understand why. I recently read a collection of his short stories, and he’s nothing short of a world class writer. Take Mother Joan of the Angels, which can and should be interpreted as an existentialist work of art or a probe sent down into the depths of hell by a non-religious person. At the same time, the writing is modern and extraordinarily cinematic. A director like Guillermo del Toro could turn it into a beautiful gothic picture. I’ve also been reading Kierkegaard.

I read on your blog that his name means cemetery.

That matched his personality, in a way. He was an incredibly sad figure. He was a result of that terrible Freudian dream of compensating a sexual calm with a storm elsewhere. I don’t mean to sound vulgar, but his fear of sexual intercourse is what made him let open the gates to God and Abraham. Of course God and Abraham, his existential longings, and that terrible anxiety had been pent up inside him all along, but his sexual impotence is what allowed him to express it all. Kierkegaard was one hell of a bastard, in a sense: he rejected a woman who loved him. Hence my message to philosophers: remain chaste.

You brought your cats with you to Copenhagen. What about your books?

My girlfriend got a good job in Denmark, so I thought, why not? I can write anywhere, after all, it’s been years since I lived in America, in Boston, and I felt like seeing a different country and spending some time there. We had to take everything we had. And this is where we run in to a certain kind of savagery: I had to weed out the books I didn’t want to take.

You’re scaring me.

Don’t worry, I didn’t burn them. I donated them to a library, which I hope is a kind of karmic compensation for all the books I once borrowed in other libraries and never returned. I hope that the forces ruling over this world saw me stumbling under the weight of my enormous bag with upwards of 80 books in it, and that they’ll forgive me for any books I lost while drunk and never gave back.

Let’s be honest: you don’t reread every book you have, and there’s no point in hanging on to them. Most books, like most everything, are stupid and idiotic. Of course it’s not just the stupid and idiotic ones that I gave away. I also gave away books I didn’t understand, books that weren’t for me, or ones that I had two copies of. But despite my efforts we still had to buy another two bookshelves.

Have you considered getting a Kindle? It’s easier to move with a Kindle than it is with a ton of books.

I bought one for my girlfriend, but…

…you use it yourself.

That’s the thing: I don’t. I rarely ever pick up the Kindle. In our household, or as a friend of mine likes to say, our home Church, we a have a regime of separate property. We each have our own computers and our own bookshelves. But I’ve made some progress: I now let my girlfriend read my books [laughs].

And that’s a big deal.

It’s a very big deal. We decided we needed to live up to the ideal of a modern couple. I’m kidding, of course, because we’re a completely normal couple. Does every normal couple have to share everything? I don’t think so. The Kindle is like a book that’s being read. It’s not something you’re supposed to take away from someone. I do borrow it once in a while when writer friends of mine send files with their work and I to have find some way to read them.

It’s a pretty nifty little device. But still can’t bring myself to get my own Kindle. Perhaps I’m just too old, but a large part of my world is tied to the screen: I work on a computer, I watch a lot of movies, I play video games. Adding yet another screen, even though the Kindle screen resembles paper, isn’t something I feel like doing.

But I behave like an idiot. I’m forcing myself to be unhappy, because I could use it more often if I would just ask. Intensive travel takes up a large part of my life. I’m in Poland now, in Warsaw, but I’m on my way to see my little boy and my friends in Kraków, and I just got in from Poznań yesterday… My refusal to switch to the Kindle means that I have to lug an enormous amount of books with me.

How many?

I don’t have too many at the moment, just three or so: Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Douglas Rushkoff’s Cyberia, and some detective novel. But I’m going to take advantage of this trip to Poland to collect, buy, and borrow some more, so I’ll end up spreading an abundance of good books. I’ll buy a book, read it, and leave it with whomever lets me stay the night, because I don’t feel like carrying it. Orbitowski roams the country spreading print.

Like a spirit. But what do ghosts do in the 21st century?

Horror fiction expresses our human fears and anxieties. It’s the flip side of the explicable world. Our world, by which I mean European culture, is more explicable than even before. But our need for the uncanny hasn’t gone away.

But why fulfill this need with a chainsaw in a cheap horror novel?

Ninety percent of horror, detective, and romantic fiction or work with experimental ambitions is utter crap. That’s just how the world of culture works.

So maybe culture in general is pointless?

Culture, in the broad sense of the word, is the only way in which we can effect permanent change in the world. And I don’t mean the progress of civilisation in the technical sense, but the world of our imaginations or, to use that ugly contemporary term, the world of memes. The world was a bit different before the Matrix, and it hasn’t been quite the same since. Books, especially fiction, are a bit different. The books that have been changing the world recently are the bad ones. The Da Vinci Code is a complete intellectual and literary failure. Or take Twilight: total trash that has nevertheless succeed in reviving the conservative, even chaste, aspect of teenage love. Two thousand pages about gazing into each other’s eyes. It reminds me of those purity rings worn by girls in the American Midwest. So what? Culture changes our internal worlds.

translated by Arthur Barys