AGNIESZKA DROTKIEWICZ: You’re a graduate of the Tadeusz Czacki High School in Warsaw, you also studied political sciences and law at the University of Warsaw, you’re familiar with musical notation and played the piano. What kind of technical abilities and predispositions does one need to become a stage manager in an opera?

TERESA KRASNODĘBSKA: Well, stage managers are like explosive ordnance disposal techs: they have only one shot at things. You need to be a multitasker with an ability to achieve intense states of concentration, nerves of steel, a few pairs of eyes and ears, at least three sets of hands, be emotionally unavailable during a show, and control things that are beyond your purview – for example, a torrential downpour about to fall down on my head (the stage humidity control system failed over the stage manager’s post during Traviata). Another time, the monitors that show me the stage and the conductor stopped working during a live satellite stream to Germany. Every stage manager, like a guerilla, needs to be prepared for these kinds of accidents, we have to manage somehow, control our nerves, control the situation on the stage, and continue with the show like nothing (!) ever happened.

Teresa Krasnodębska

Stage manager at the Grand Theatre-National Opera in Warsaw, where she works since 1977, and on the stage since 1982. She cooperated among others with: Laco Adamik, Marta Domingo, August Everding, Maria Fołtyn, Achim Freyer, Marek Grzesiński, Agnieszka Kreiner, Andrzej Kreutz-Majewski, Harry Kupfer, Marek Minkowski, Krzysztof Penderecki, David Pountney, Robert Satanowski, Mariusz Treliński, Krzysztof Warlikowski, Emil Wesołowski, Robert Wilson.

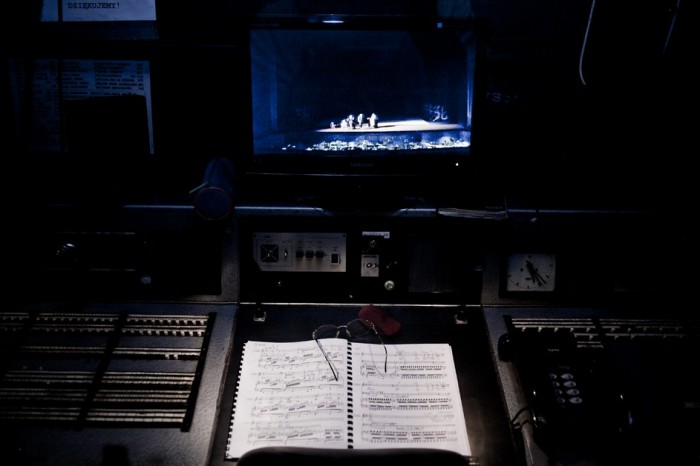

Her workplace – stage manager’s post – looks like the cockpit in a pilot’s cabin and it’s a post operating ever since the Grand Theatre was reconstructed after war damages and opened to public in 1965.

This is where stage manager runs the show from the first call to the very end. Among various buttons there is also a “doctor call” – pressing it enables a lamp in a seat of a doctor present at every performance. When the lamp goes on the doctor leaves the audience, knowing that someone needs help.

Ever since Teresa Krasnodębska was almost tread down by a horse running from the stage into the backstage, the stage manager’s post is protected with a plexiglass.

You acquire these skills over time, with practice. But: under no circumstances can practice become routine, the latter is terrifyingly dangerous to our profession. You need a lot of mental stamina and imagination. Of course, knowledge of musical notation is absolutely basic. You need to know or learn a few languages – it’s better, safer and more professional to understand the lyrics of a show you’re trying to run. Besides, we often have visits from producers, singers, dancer and conductors from around the globe and you just have to have a way to communicate with them. A stage manager runs concerts, recitals, musical matinees, ballet and vocal competitions, the La Folle Journée festival, assists with guest performances in the National Opera. The manager is also responsible for shows that feature no actors, where the mechanics of our stage is the protagonist (Theatre Without a Curtain). I also managed to perform in an opera once, I played a... stage manager, a character devised and introduced into the show by the director.

Is there a school for future stage managers?

The legendary Theatre Techniques High School closed its doors in 1969 (it was replaced by the Theatre Techniques College, sans the stage management department), besides, they only taught theatrical stage management, doing that job at the opera is different. Therefore, you learn the stage management trade according to the ancient rule of “master and apprentice”. I learned it this way and at some moment I myself started teaching a younger generation of future managers. Kasia Fortuna, the youngest of the four stage managers we have on staff, was such an apprentice. She started working at the theatre as a volunteer, when she was still studying musicology: she worked the ticket booth and brought flowers to the artists on stage. Working in the theatre appealed to her and she decided to become a stage manager. She has been on her own for three years now, and we have a tremendous working relationship.

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

So you probably need solid psychophysical abilities to do this job, combined with a talent for smooth collaboration.

Yes, it’s very important, because the stage manager is a liaison between the artists, the run crews, the management and the administrative staff. The artists are the most important ones, of course, but on the other hand you can’t run a theatre without a running crew, so you need to be able to pat both on the back and ensure that there is much love between them.

Does being a stage manager include providing motherly support to the people you work with?

When we took Mariusz Treliński’s version of Othello to Japan, José Cura, the actor who performed the eponymous role told me: “Teresa, you’re like my stage mother!”

Do you ever hug people?

There are times when you have to go “There, there,” to hug someone, talk to them, soothe them, joke around to relieve some built-up tension. Generally, you need to take care of the artists, they need to feel good, need to know that they’ll be asked to step on stage at the right moment, that if they ever need something backstage, be it a glass of water or help from a dresser, they will get it. The actors need to know that the stage manager will always keep them in mind, even when he or she has a show to run. This requires particular mental predispositions that are not all that common. Some people get so caught up in reading sheet music that they stop reacting to all external stimuli.

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

Your post looks like the cockpit of a jet airliner. I think the comparison especially apt, because just like a professional pilot, the stage manager also has to look professional and calm even when everything goes wrong.

You simply cannot look nervous in front of the people you’re managing – and I’m no different from any other human, I have fears, emotions get to me. To this day premieres make me nervous in some way. It’s a completely different set of feelings than what I experienced back in 1982 when I managed my first show – I remember pushing the button that would allow me to welcome the audience something like 10 times. I was aware that a great number of people is sitting on the other side and I couldn’t see them, it was terribly stressful! To calm me down, the long-time conductor at that theatre, maestro Andrzej Straszyński said to me: “Imagine you’re talking to only one person, and smile at them.”

Do you have any pre-show rituals that are supposed to relieve the stress?

Half an hour before a premiere I paint my nails.

Any particular colours?

Something elegant, I stay away from greens and dots. When we were staging Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelung tetralogy, directed by August Everding, I was needed in the audience during the last tech rehearsal for Twilight of the Gods, the last opera in the cycle. So I sat far in the back, away from the director, the set designer, and the lighting tech and I started to paint my nails (luckily that particular polish didn’t have an intense smell).

Suddenly, one of the directors working at the theatre approaches me and says: “Unbelievable, everyone’s close to snapping from all the pressure, and here she is, painting her nails!” I calmly replied (even though on the inside I was just a tangle of frayed nerves): “That’s right, because this particular activity requires me to be absolutely calm.” The show went great.

I’ve been doing it ever since.

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

The French word for stage manager is regiseur, while director translates to metteur en scene.

Yes, the Russian term for stage manager literally means “the one leading the show”. The stage manager has to realise all the ideas coming from the director, the conductor, the choreographer and the lighting designer – they’re the ones who create the show – they’re the key producers, while the stage manager belongs to a group of co-producers that also includes heads of various workshops, assistants to the producers, lighting and sound techs.

Does the director sit in the audience during a show, and not somewhere near your post?

Absolutely! The director should sit as far away from the stage as possible during a show. The reign of the director ends at the last rehearsal. Then the stage manager takes over and everybody has to submit to the will of the latter. It’s like with air traffic control – you need single, final decisions.

So you can’t have any assistants?

I always have one – there’s an assistant stage manager, but he or she stays on the other side of the stage. Sometimes, the assistants walk around the stage to control the situation, they have their own set of tasks, but the leading stage manager has to control the entire show.

When we were taking our shows abroad during the tenure Robert Satanowski, Sławomir Pietras or Jacek Kaspszyk, we always took the entire theatre on the road: the orchestra, the soloists, the ballet, the choir, all the run crews we needed – but back then I went by myself, there was no assistant stage manager.

But when we’re staging something at home, there are always two managers at work – one of the reasons behind this is that when something happens to the leading manager, the assistant takes over the panel as if nothing is wrong – the show must go on, the curtain has to go up every day, no exceptions.

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

Do stage manager panels look alike in theatre across the globe?

Every theatre has a different one! Some are so small that they barely have a place to hold the sheet music, sometimes it’s only a table equipped with a microphone and a monitor, while others are incredibly sophisticated, they look like something out of a NASA flight control room. The most important part of any panel is its communications module. When we were working in Japan – 11 shows, the same opera but in eleven different cities and theatres – each day we worked in new one. Every theatre had a different stage, a different auditorium, but the Japanese run crew that accompanied us had all of these places down pat – working with the Japanese was simply fantastic. Each day had a surprise in store for me – where am I going to be working from tonight?

As long as we’re talking about different spaces – in our theatre, when you look from the stage towards the audience, you see the “Moliere side” on the left (because Moliere Street runs behind the wall) and “Wierzbowa side” on the right (that’s where Wierzbowa Street is).

This nomenclature was devised a long time ago by our dear friend Stanisław Zięba, a lighting tech and old theatre hand. It’s a pity he didn’t include the “Fredro side”, that would’ve been both beautiful and spot on. These names are necessary because the director always looks at the stage from the audience, while the crew, the mechanics – look at everything from the stage. So when the director shouts to put something on the left, the crew runs towards his right, so we use these names to keep everything straight. The nomenclature comes from Moliere himself who had a “garden” and a “courtyard” side in his theatre (our “garden” side is on our “Moliere” side so I’m basically working in the garden). These names we use serve us identically in every corner of the globe – whether we’re in Osaka, Poznań or Paris, when the stage manager says: “Attention, male choir coming in from the Moliere side,” everyone is on the same page.

Do you consider your job addictive?

It is for me, very much so. I wasn’t the first one to think of the metaphor, but the floor of the theatre is like a roach motel: once you enter, you just can’t leave.

Looking back, what were the most difficult shows you managed in your career?

Right now, I’m basically judging the difficulty by looking at the complexities of the musical side. I remember that doing Penderecki’s The Black Mask with Albert Andre Lheureux in the director’s chair was very hard for me. I wasn’t very experienced and the music was terribly complicated, as it usually is with Penderecki – as soon as your eyes leave the sheet music to check the stage, you’re lost, you don’t know where to go back to. Trust me, it’s very different with Verdi or Puccini (both of whom I love).

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

Given how well you know your theatre, is there an opera you would like to see staged there?

I dream of someone doing a beautiful, witty and modern rendition of Moniuszko’s The Haunted Manor, on our “fully open” scene (the one by Piłsudski Square), using our stage equipment, lighting and projection capabilities. The version I’d want to see would be done in the spirit of Sienkiewicz and Fredro, with appropriate costumes, but without making it look “olde-worlde” and whatnot. And it should definitely feature great Polish singers! Why shouldn’t we leave an opera happy? Or in a state of reverie?

I love Ferdinand Hérold’s The Wayward Daughter, it used to be my favourite ballet performance, I haven’t missed a single one we staged and I’ve served as stage manager on nearly half of them. It requires a great amount of artistry and acting chops from the performers, and it still remains very witty, just like Frederic Ashton’s Cinderella. The audience – the whole audience, not just the kids – has a great time. There are a lot of comedic operas, The Barber of Seville being one of them. I once heard a radio transmission of The Barber from the Metropolitan Opera, and you could hear bursts of laughter coming from the audience. We don’t laugh nearly enough, laughter massages the liver and oxygenates your brain.

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

What are the stages of preparing a show, from your particular perspective?

We pick up a piano reduction from the library and start with ensemble rehearsals with soloists. All of the ensembles that take part in the show – the orchestra, the ballet, the choir, the soloists – start rehearsing individually. Each ensemble has its own inspector and the latter are overseen by the stage manager, who also participates in the rehearsal to get acquainted with the musical material.

Learning material used to more complicated as there were no available recordings. If someone could play the piano, you could play for yourself (the stage manager rooms used to have pianos); everyone else bought records or tapes and listened in closely. Nowadays, especially when we’re transplanting other shows into our theatre, people supply us with complete DVDs, piano reductions from the theatre that the opera premiered at (you have to prepare your own reduction while working on the script), suggestions from the lighting designer – it seems that rehearsal with all that material will be a cakewalk but that’s just an illusion.

Personally, I like building shows from the ground up: when all professional ensembles are familiar with the material, we meet on a small stage to rehearse with a piano or a CD and the stage manager writes down all the instructions from the creators on sheet music (pencils and erasers are the most important tools that the stage manager has during those rehearsals). The show starts to come together in its most basic form, filling out over time. We finally get up on the main stage, the musicians show up, the stage design goes up, the lighting and costumes are arranged. And then everyone – both artistic ensembles and technical crews – are ready to start dress rehearsals.

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

photo: Krzysiek Krzysztofiak / krzysiekrzysztofiak.com

During special rehearsals, all technical crew prepare their scripts – signal no. 1: moonrise and smoke over the fjord; signal no. 2: sunset, the ship enters the port; signal no. 12: a small junk floats by; signal no. 32: the palace of the gods crumbles and falls, lightning strikes, the witches attack, there’s a tornado, lighting effects, a nightingale in a grove, a demon appears, the revolving stage turns, the trolleys come closer, the trapdoor opens, a limo explodes, a city catches fire, a golden rain falling down, everyone takes a bow and then the curtain falls.

All of these effects are managed by the stage manager – he or she calls up the appropriate tech crews in the appropriate moments, because the techs can’t be on stage all the time – there is no such need, besides, they need a break. So they wait in their rooms for the call to come, passing the time, watching sports.

Artists also get off the stage, have their breaks. You’re the only one who doesn’t get to watch anything else than the feed from your stage monitors.

A long time ago we had these old monitors that allowed you to switch channels, so when I was managing a show that everybody was already familiar with I switched the channels and watched a football game – no sound, of course. We had to watch ourselves, I had to make sure that the guys who were standing there next to me didn’t just start hollering “Goooooal!”

But that was a long time ago...

Warszawa, 19 May 2012

translated by Jan Szelągiewicz