ALAN LOCKWOOD: The King Roger you are directing at Santa Fe Opera will be the latest production of Szymanowski’s piece. What are you focusing on as the opera’s core issues, and how do you find these manifested in the title character?

STEPHEN WADSWORTH: The bones of the story of King Roger are very simple. A marriage is falling apart. Along comes an attractive force that presents both spouses with a choice: stay or go. To complicate the matter dramatically, Roger is in a position of great responsibility, and his citizens become involved in a way of life on the edge of lawlessness, of rule breaking and foundation challenging. Roger becomes fascinated with this force, how to address and control it, but he is simultaneously tempted to allow it to control him.

There are lots of ways that people can approach the story. But there’s no question that emotional intimacy is an issue for Roger. And something about physical intimacy is deeply challenging to him. The wrong-gendered person comes into the room, compelling, invasive, absolutely challenging and unswerving in what he is preaching, which is essentially free love. Roger is very nervous: it’s like he’s on his first date. With Edrisi, the wise royal advisor, in the second scene, he says “My heart is in my mouth, I can’t figure out what to do.” It’s clear that for Szymanowski, this was an exploration. The scenario clearly deals with his sexuality – trying to figure out if it was something he could live, as opposed to dream or imagine.

In the years before he began composing King Roger, Szymanowski had traveled to Italy, Sicily and to North Africa.

Stephen Wadsworth

Stephen Wadsworth has directed opera and theatre with companies including Alla Scala in Milan, the Vienna State Opera, Covent Garden in London and the Metropolitan Opera, where his production of Boris Godunov was conducted by Valery Gergiev, and where his production of Handel’s Rodelinda was revived in autumn 2011, starring Renee Fleming. Wadsworth wrote the libretto for Leonard Bernstein’s opera, A Quiet Place. He worked with Maruisz Kwiecień while heading the Met Opera’s Landemann Young Artist Development Program, and directs opera studies at the Juilliard School in New York City.

He was super inspired, in those travels, by exposure to attitudes that didn’t demonise his sexuality. And then was challenged, when he came back north to the cold manor and sat to work: how might orchestral colours show all that? As in “I’ll write a piece of music that no one could write unless they’d really opened up the doors and welcomed in a sensual awareness.” You can make King Roger not gay or gay, you can be just as open as you want to be, but this sensual awareness is one aspect of the piece you can’t get away from.

The recent performance history of this opera is about visions of excess, where lots of symbols crash into each other, lots of excessive behaviour and symbolic behaviour. Actually, what the cast does in the Warlikowski production (at Opera Bastille in Paris in 2009, and Teatro Real in Madrid in 2011 – AL) seems to me quite interesting, more so perhaps than David Pountney’s people (at the National Opera in Warsaw in 2011 – AL). Both productions are totally out there, but there’s more of a sense in Warlikowski’s of these people struggling with the things Szymanowski was thinking about. With that said, I may well feel differently about both of those productions, after directing the piece myself.

I want the viewers to have a strong identification with the people on stage, not to have the music be a soundtrack for a visual bonanza of symboliste decadence. If I didn’t deal with the intimacy, but there was overt sexuality, no one would be shocked. And they probably wouldn’t be worried. But the minute that the Shepherd, sung by William Burden, walks into the room and the two men just look at each other – or the two people, because the same thing happens with Roxana, sung by Erin Morley – it’s got to be unsparing. It’s the intimacy in the piece that you can’t get away from, and there won’t be much scenery on that vast stage to get in between us and it.

Clearly when we meet Roger, he’s burdened, in some kind of torment, not connecting with Roxana. Edrisi says, in the second act when they’re waiting for the Shepherd, “When was the last time you kissed your wife with passion?” That could be supporting evidence for any of the things we’re talking about, but clearly the marriage is in some kind of stasis.

And clearly she’s wonderful – Szymanowski reworked her exquisite second-act aria into an orchestral song – so it’s not about Roxana.

She’s got to the point where she needs to push the envelope. She needs to encourage debate. Push is coming to shove in the marriage, and it’s about intimacy. It’s just the most invasive, complex subject there is.

Stephen Wadsworth,

Stephen Wadsworth,

photo: courtesy of the Santa Fe OperaHow will your approach maintain what is so important yet elusive?

I am trying to be nonreductive about it. The stage will be set up in a certain way, with various visual homages to the symboliste painters, the Byzantine, and the eastern and western influences in the piece. Szymanowski’s life was exactly simultaneous with Freud’s career, so fin de siècle Vienna, Jung, inter-war Europe, early Hitler, as well as other leaders in moral and personal crisis, are as much parts of the fabric of the piece as medieval Sicily, where it is set. We’re in the very end of the Victorian era, in the sense that complicated psyches are about to burst out into new ways of living in moral and sexual freedom. When Szymanowski was writing King Roger, he wasn’t surround by Fitzgerald-era flappers flaunting convention for the sake of it, in a free America.

He had seekers around him. He was close with Witkiewicz, whose painting and portraiture and writing remain challenging work, and Artur Rubinstein, who interpreted his piano music and later helped bring him on concert tours in the United States. Bronislaw Malinowski was another member of those circles, and was formulating structural anthropology in books including The Sexual Life of Savages, then taught in London and at Yale University.

Szymanowski had brilliant sensibilities. His was obviously an intellect with a mixture of analytical thinking and sensual needs, and a deeply unsatisfying emotional life. Think of the 1920s. Europe is emerging from a war that fractured it utterly, Poland is reborn but, as ever, squeezed by its neighbours: Germany, where the Weimar Republic is a pressure cooker of anarchic art, and the new Russia, which is losing many of its best artists to western Europe. There’s Diaghilev, and Szymanowski was I think deeply influenced by Diaghilev’s collection of artists. There’s a wonderful description, in Rubinstein’s memoirs I think, when he talks about sitting in Paris in some restaurant with Diaghilev and then there’s this depressed, obsessive, black-hole Szymanowski sitting there, mooning after the guy who’s with Diaghilev. He was pretty dark by all accounts, and suffered from severe depressions.

Erin Morley (Roxana),

Erin Morley (Roxana),

photo: Ken Howard, the Santa Fe OperaHis fascination with the melting pot of Sicily and with the multicultural, open-minded court of Roger II also tells us something about his intellectual and emotional Gestalt. Roger’s court was for Szymanowski perhaps a fantasy or an ideal of tolerant discussion on all subjects, and Sicily itself hosted a melange of cultures – western, eastern, middle-eastern, Christian, Islamic and so on – seemingly in opposition but somehow harmonious on this island. There will be some Eastern figures in the court in our production.

Eastern figures as members of the court?

And as visitors to the court. The opera has symboliste aspects, some of it very Christian, some very un-Christian, some of it Muslim and North African. I was in Vence when the attacks of

11 September 2001, occurred. We weren’t able to fly to the States, and got on a plane to Sicily. We were wondering how you could sightsee after 9/11, and Sicily gave us our answer. Everywhere the architecture is a merging of Muslim and Christian cultures. It was very heartening, and that experience helps me understand something of what Szymanowski felt there.

Szymanowski’s writing provides an attractive, compelling, mysterious mixture of unfamiliar Eastern influences. Eastern European history often features the constant threat of the Ottoman Empire. In Poland, obviously, this is in the national memory, a fear that is also alluring.

The Polish king, Jan III Sobieski, led the relief army in 1683 that turned the Ottomans back at Vienna.

And the threat of the erotic was also part of the west’s fascination and fear of the east. Ecstasy is imagined and expressed in different, titillating ways, ways that were not at all western European, which is all about buttoning up. That excitement was of course naively idealistic, often wrong, and there’s a kind of easy superiority in it, and fear. But exposure to eastern thinking and art galvanised Europe in the 18th century, the 19th, and the 20th. Szymanowski challenges Roger with a new, radically different, east-inspired way of life: if you open yourself to it, if you’re really open, what would happen?

In these ways, is King Roger a timely piece to be exploring?

I wonder about that. I think it is more timely because of the weird universality in the mythic element of the story. In that sense, I think King Roger is one of the great stories. It is so hard won, what Roger comes up with. His search is like bobbing for French fries – it’s dangerous, he gets burned, terribly hurt, lost, terrified. But in the end he also comes up with a way of seeing that seems to be relieving. He seems glad of having gone there.

The opera’s working title was The Shepherd, in the years that Szymanowski and the librettist Iwaszkiewicz were developing it, before Szymanowski drew the focus to Roger.

It’s still called that, parenthetically. For Szymanowski, it was a hymn to the fabulousness of what he’d encountered in Sicily and North Africa. It’s not just about whoever those boys he met were. It’s what that represents, that relief of true identity, of freedom. It’s huge, and raw, like „I haven’t been able to feel like myself.” A lot of people live with this: if they’re gay, if they’re dyslexic but don’t know it, if they’re Jews in Nazi Germany, if they don’t believe in the God they were taught, and so on. Then learn about others who share their plight, and may eventually find a life free of that sense of fraught differentness. This must have been Szymanowski’s deepest wish.

Or if they’re in a relationship with a spouse that they haven’t kissed ardently in too long.

Yes, that is so true, we sometimes find ourselves entrapped in complex relationships that really are wrong, or damaging, for us. Perhaps that’s part of what is ailing Roger and Roxana, though they clearly love each other deeply. Their problem seems to be –

Intimacy.

(Laughs) Yes. You know, it’s the only shocking thing left in the theatre. It’s the only thing that will shut the audience up, and you will hear a pin drop.

‘King Roger’ at the Santa Fe Opera

The Santa Fe Opera premiered King Roger by Karol Szymanowski on 21 July 2012, directed by Stephen Wadsworth and starring Mariusz Kwiecień as Roger. It is the first new US production since Lech Majewski directed the opera at Bard College in 2008, along with Szymanowski’s ballet, Harnasie.

The Santa Fe Opera is the second largest producer of new productions in the US, after the Metropolitan Opera. To achieve the full sound of Szymanowski’s orchestration, SFO has added two dozen orchestra musicians, and a similar number of additional choristers. The guest conductor is Evan Rogister, who is cited in the August issue of Opera News as among the two dozen rising stars in US opera.

In the US you can do it sometimes with a kind of sly, challenging political incorrectness. There’s an interesting moment in Master Class (Wadsworth’s production of the Terrence McNally play about Maria Callas transferred from Broadway to the West End in London, at the time of this interview), which we chose to mine because it’s perverse. She’s introducing herself to the pianist, who as it turns out played for her yesterday. He says he’s Emmanuel Weinstock. She says, „Emmanuel.” He says, „Yes.” She says, „That is a Jewish name, I would imagine.” He says, „Yes.” She says, „And are you Jewish?” And he looks out at the audience and says, „Yes.” And he nods. (Slows) And she pauses, and says, „I don’t think there’s a single person in the auditorium that doesn’t realise that...” And of course you think, is she going to say something horrifying about Jewishness? But she says something about what they’ve just been talking about: She reverts back. Boy, was that audience quiet and alert in that moment.

Intimacy, it’s a weird thing. You can take your clothes off onstage – it’s not shocking. You can put up a badly thought-through production with a lot of garish choices – people will just think it’s dumb. But if you have a scene where people look at each other – especially people who are very close, who need to be close or need to maintain closeness but are having issues with each other – that gets people’s attention. I find it essential to good theatrical story-telling

When did you know you could develop this core of intimacy in King Roger?

When I listened to it. What interests me, especially in opera, are complex relationships, and playing a scene in terms of who the person is and what that person wants or needs at that moment. There’s not a lot of complex work being done in opera. It’s a given in theatre, where we sort of expect it. I think directors need to do it in opera. You can only get the audience in on the people, you can’t get them in on the scenery. What’s scary is people developing needs, bumping into one another. The degree to which people are able and unable to make contact is what gets a human being’s deepest attention in the theatre. Or keeps their attention—there are a lot of things that can get attention, but not keep attention.

Roger carries something from his conflicts into the dawning day, the new, Roxana-less day. He’s lost both the figure of his wife and the animus figure, Dionysus, the Shepherd. The yin and the yang were pulling him in different directions. He lost both of them, but perhaps gained a clearer sense of his true self, his true identity. And it’s purifying. He’s ready for the next chapter. Ready to move on.

With the orchestra playing a C-major chord.

Right. Szymanowski made a wonderful musical synthesis. Like in the Betty Boop cartoons, where the background looks like an acid trip – it’s insane what those guys put in there. This score is the orchestra letting go of control, letting it fly with all of this sensuous experience, hardly ever certain of its key for long, meters constantly shifting, and ultimately dissolving into a big, blinding, C-major sun chord.

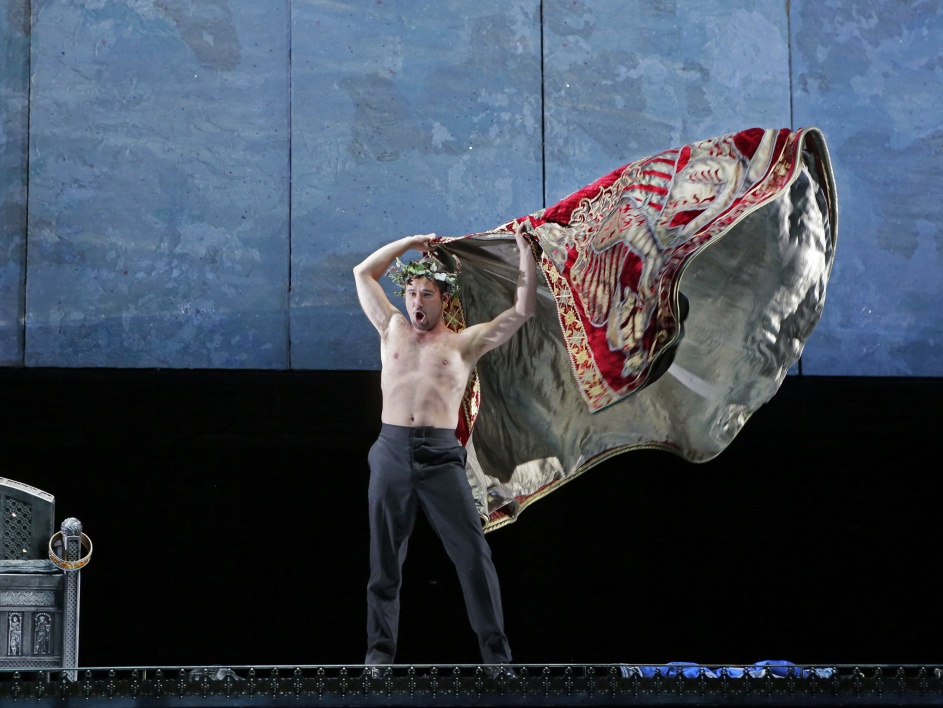

Erin Morley (Roxana), Mariusz Kwiecień (King Roger), chorus and dancers, photo: Ken Howard, the Santa Fe Opera

Erin Morley (Roxana), Mariusz Kwiecień (King Roger), chorus and dancers, photo: Ken Howard, the Santa Fe Opera

How have your lead singers played in to your preparations?

I know them very well, all of them. Erin Morley is a former student of mine, from the Juilliard School and the Metropolitan Opera’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program. She and I had some terrific artistic experiences in the classroom – I was the teacher and she was the student, but really, when teaching is working, it frequently feels like the relationship is the other way around. Erin is fearless and will go there. Mariusz was in the Met program also. Mariusz is like a tiger. He is an actor, a person who will go anywhere and can channel every kind of human experience.

These people are fascinating, and are wildly intelligent as well, people I’ve known for years, and I love them. My perception of them plays a role in how I imagine this production playing out. Not just because in rehearsals we’ll say, “How about if I do this?” But before that, when I’m thinking, “What if this particular actor does that?” That’s thrilling, because if you’re really going to do the play, you’ve got to cast the play first. It’s exciting to look forward to a project where I know the conversations will be as sophisticated and complex as with any actors I can think of.

I’ll set up, as I’ve always tried to do, encounters for these people, in all possible combinations of the characters. Allow them to see each other, want each other, need some effort from that other person, while they are forcing the audience to consider: what is that relationship? There’s an example in Rodelinda (Wadsworth’s 2004 production of the Handel opera, with the Metropolitan Opera – AL). It’s during an aria for Rodelinda. There’s a very dense staging for all the characters present, and they’re all coming into conflict in various ways. There are many, many musical beats of everyone looking into one other’s eyes, and also into themselves. It forces the audience to work on it, to figure out what it’s about, how the relationships work, what the characters’ private preoccupations are. Of course you have to tell the story, you can’t just leave them standing up there. But these underlying encounters are powerful in themselves.

Is King Roger a liberating piece, in its message, or in its conclusion?

Yes, but ultimately you have to be careful about saying it’s one thing or another. Yes, it’s a C-major chord at the end, and yes, Roger sings, “Oh, the sun! The sun!” But it’s not necessarily a clear, breathtaking, flawless C-major. There are a lot of wrong notes that are going to go on in that man’s head for the rest of his life. Yet there’s no question but that Roger wakes up from a dream, in the words of Edrisi, and is ready to move forward into a new version of his life. He does not follow the Shepherd like the others – and even among the others, there might be several who remain, soberly chastened by where they almost went.

Roger has made huge sacrifices to discover and own what he finds at the end. Nothing is easy in his world. Or ours.