It’s a small thing to build a locomotive:

Wind up its wheels and off it goes.

But if a song doesn’t fill the railway station–

Then why do we have alternating current?

Vladimir Mayakovsky, Order to the Army of Art, 1918

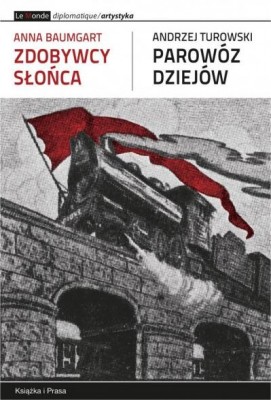

The film Conquerors of the Sun by artist and filmmaker Anna Baumgart and the accompanying book The Locomotive of History by art historian and critic Andrzej Turowski together tell a compelling story. Complex and fascinating as it is, it’s hard to properly respond to it without giving at least a short summary. The story starts with Turowski himself being offered in late 1990s Moscow, in exchange for a bottle of Ballantine’s scotch, access to a batch of top secret papers from the early 1920s. The documents turn out to include both names of early Bolshevik power as well as those of major avant-garde artists, teaming up for a major art and propaganda project.

After years of preparation, in 1921 – four years after the October Revolution, when the Polish-Soviet War had only just been ended with the signing of the Treaty of Riga – a propaganda train leaves Moscow, bound for Berlin via Poland. Dubbed “Locomotive of History” but camouflaged as an ordinary freight train, it is packed not only with agitprop material and military cargo to help boost revolutionary efforts in the West, but also major works of Suprematism. The men responsible for bringing most of these pieces together are trailblazing artists Kazimir Malevich and Władysław Strzemiński, whom had met in Moscow, and had become members of numerous commissions planning contemporary art museums throughout Russia. What they dream of is a new kind of museum: educating the proletariat how to see, how to appreciate contemporary art. Sharing Polish backgrounds, Malevich’s and Strzemiński’s intention was to include paintings on the train that would form the basis of a future museum of modern art in Warsaw. Part of the mission of the train was also to create closer links between avant-garde artists in Easter and Western Europe.

However, the political turmoils of these years didn’t help matters: whether it was the increasing limitations to artistic freedom under the Bolsheviks, the faltering economy, or the migrations of Poles in the wake of the Riga Treaty. The train got stuck for around a year in sidings in Poland, involving diplomatic complications and top secrecy, so that Malevich and Strzemiński literally lost track of it. Worried, Malevich tried to find out about the train’s whereabouts, and as it turned out, on its odyssey of years and years, it had been sent to Berlin. But here the diplomatic sensitivity of the matter didn’t decrease, and eventually the train, still sealed and unopened, was sent back to Russia via Poland.

Meanwhile, Strzemiński and his wife the eminent sculptor Katarzyna Kobro had changed plans and, having relocated to the town of Koluszki, decided to push for the idea of a future museum of modern art in nearby Łódź. By that time Strzemiński had all but given up on the train, and was all the more startled to learn that it was held right in Koluszki, a major railway junction. But all attempt to gain access to it failed, and eventually, it seems, the “Locomotive of History” was obliterated by an explosion in 1930, including all its cargo. As Turowski writes towards the end of his book, the train had become “a political spectre haunting, like a dead soul, the yellowing papers” that he had obtained in return for a bottle of whiskey. So much for my short summary.

Anna Baumgart, Conquerors of the Sun, 2012, film still, courtesy of lokal_30 WARSAW

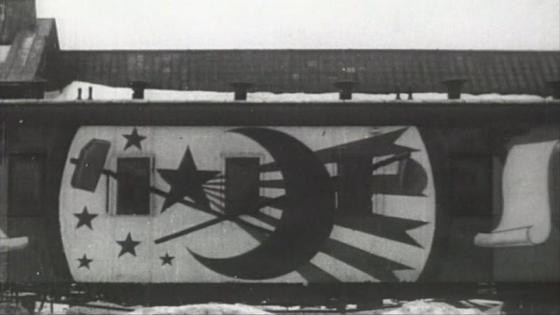

Anna Baumgart, Conquerors of the Sun, 2012, film still, courtesy of lokal_30 WARSAW

Baumgart’s film opens with a mesmerising sequence from a silent movie that, as we are told, was shot by the young revolutionary poet Vladimir Mayakovsky himself. He is seemingly struck by the charms of a young lady he meets in a garden, and in one close-up during a classroom scene in which he sees her again – she is the teacher – we see his eyes widening as if in shock, or epiphany, and that very moment is looped twice. Has his love been fully aroused? Or has he just realized he has been betrayed? We don’t know, but in any case, “it was revolutionary poetry [...] that led me to the flat of Mr. & Mrs. K.,” says Turowski, interviewed, about what brought him to he place where he would eventually get hold of the secret papers that prompted the film, and his book. It was because of figures such as Mayakovsky that Turowski started his research – because of figures who wrote poetry about being a handsome lover and pamphlets for heroic revolutionaries all at once, who were ready, if need be, to strike up a “conversation with the taxman about poetry” (the title of a Mayakovsky poem from 1926). Or to put it in the purposefully flippant words of the Russian-American novelist Gary Shteyngart, Mayakovsky was “the first and only early-Soviet rap star”. And just as some American rap stars such as 2Pac, like Mayakovsky capable of the “intimate yell” (James Schuyler), this is a tragic star who died too early. As Roman Jacobson, the groundbreaking linguist and literary theorist, observed devastatingly with his 1930 essay On a Generation that Squandered Its Poets, in fact a whole generation of Russian revolutionary poets starved, wasted away, or committed suicide like Mayakovsky, marginalized, ridiculed, and often directly persecuted during the early years of Stalin’s reign.

But then of course, as the film’s story unfolds, were are thrown into the blazing heat of the early years after revolution, prior to things being shock-frosted by the following Stalinist terror. The attention switches from the restless energy of Mayakovsky to the more quiet struggles of Malevich and Strzemiński, and a mesmerizing suite of images ensues ... a Russian ca. 1940s newsreel with its quick succession of Red Star, the Kreml, farmer, bicyclists, functionaries meeting, all accompanied by the kind of triumphant fanfare music typical for newsreels from all around the world... as Turowski recounts his story of finding the secret papers, the voice-over mentions meetings under the presence of “...the highest echelons of power”, illustrated with an image of Lenin giving a speech from a balcony, next to a big red flag... more contemporaneous footage, of Russian intellectuals meeting, of steam trains fitted with agit-prop material... the narrator reads out a quote from Malevich from an artists’ council meeting of 1919, an appeal to the youth “... to tear off the mask from your faces, file off the rays of sunshine, so that the creative light would touch upon the new dawn of the intuitive superwisdom of phenomena and the mystery of night. Fly away from narrow calls of professionalization, towards worldwide development, the spread of revolutionary art beyond the boundaries of nations.”... and while we hear that quote, we see members of today’s “Occupy Wallstreet” movement during a demonstration in New York, chanting “Eat the rich, feed the poor!”, as if Malevich’s strangely overblown and pompous appeal was still flying through the ether, like a radio message lightyears from home, almost a century later... another striking image from an old propaganda newsreel: a man pounding an earth globe in chains with a big hammer... school classes lead to a propaganda train, accompanied by Alexander Mosolov’s modernist music of 1927, his symphonic piece The Iron Foundry, with its dramatically threatening brass section and flurry, nervous strings, like machinery gone crazy... a phonetic Dada poem, books thrown from propaganda trains... explosions – the Polish-Russian War... and then switch to talking heads today, scholars in the history of revolutionary movements, or in Russian-Polish avant-garde, all confirming the findings of Turowski... a blast! The train is finally blown up...

The film ads up to a persuasive documentary, the kind of short feature you might come across late at night on history channel, when the more sophisticated, auteur-defined ways of storytelling mix with the conventions of the genre: accounts of eyewitnesses and scholars, suggestive use of music, persuasive voice-over combined with rhythmic sequences of found footage, all meant to make you fully believe in what you are told...

Anna Baumgart, Conquerors of the Sun, 2012, film still, courtesy of lokal_30 WARSAW

Anna Baumgart, Conquerors of the Sun, 2012, film still, courtesy of lokal_30 WARSAW

But wait a minute. Something perplexes me. Prompted by Turowski’s and Baumgart’s project, I have looked into the few firsthand sources available to me about Strzemiński – and I can't find anything about the train in them. I feel humbled by my inability to read original Polish, lest Russian sources (I can't even decipher Cyrillic), and realize how little this artist and pioneer of modernist art theory is actually known in the West. Strzemiński’s theory – and painterly practice – of Unism puts forth a new kind of painting that rejects not only the dualism of image and represented reality, but also the traditional logic of painterly composition in general, in favor of a uniformly flat plane. The aim is to produce a unity between painting and object, so that, as Strzemiński writes in 1928, the “picture is not an illusion of a phenomenon seen elsewhere or simply imagined and then transferred into picture, but that it exists in itself and for itself.” Isn’t this an anticipation, by several decades, of Clement Greenberg’s painting theories about flatness and the rejection of illusionist space in painting, and the work (and theoretical argument) of artists such as Frank Stella in its wake? Isn’t it all the more absurd that this anticipation until today, in the Western hemisphere, is largely not acknowledged? Moreover so taking into consideration that Strzemiński – by co-creating the International Collection of Modern Art including 111 avant-garde art pieces of great quality of works by the likes of Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst or Theo van Doesburg – also significantly pushed towards the founding of the Łódź Museum of Art, in 1931, at a time when New York’s MOMA was still just a provisional venture without a permanent location that had started three years earlier with an initial gift of eight prints and one drawing?

But back to my perplexity about not finding anything about the train in other sources. This same Strzemiński, whom pushed Malevich’s Suprematism towards a Unism that strangely anticipated the dominant US post-war art and art theory, and who helped one of the first museums of modern art in the world on its way, is also the person who according to Baumgart and Turowski is concerned for years and years with the project of the “locomotive of history”. The fact that there is no mention of it in his 1928 Unism in Painting manifesto is not surprising – this was a treatise that wasn't concerned with the practicalities of propaganda or founding a museum. But in the exhibition catalogue published by Łódź Museum of Art in 1994 (Władysław Strzemiński 1893-1952. On the 100th Anniversary of His Birth), there is a detailed chronicle of Strzemiński’s life – and the train is not mentioned in it at all.

For the year in which the train, according to Turowski and Baumgart, got on its way, 1921, the chronicle just notes that the artist and his wife Katarzyna Kobro “‘smuggled themselves’ into Poland”, and that “surprisingly there is no evidence of the artist’s creative work in that year”. For 1930, the year the train was supposedly blown up, the chronicle lists a busy schedule of exhibitions and publications, further efforts to gain gifts for the International Collection of Modern Art, negotiations about the location for the museum in Łódź, a summer heat stroke, and teachers including Strzemiński going on strike due to irregular payments. No mention of a train.

The reason for this could be explained with the very details that Turowski gives in his account: the train was so top secret that it wasn’t until the late 1990s – i.e. after the publication of the aforementioned catalogue, for which he himself had contributed an essay – that he came upon these sources by chance. The reason why it had remained secret for so long is, however, another matter: was it that its state of limbo was a cause of continuing embarrassment? Or was it that the (post-)Soviet Union had no interest in admitting that the same artist who had “defected” to Poland in 1928 had been so instrumental in a major effort of bringing together a significant collection of the kind of art that had been denounced and neglected under Stalin?

Anna Baumgart, Conquerors of the Sun, 2012, film still, courtesy of lokal_30 WARSAW

Anna Baumgart, Conquerors of the Sun, 2012, film still, courtesy of lokal_30 WARSAW

In any case, there did exist propaganda trains. Already in 1920 Arthur Ransome, British Moscow correspondent of the Daily News, wrote his famous report The Crisis in Russia. Ransome was friendly with Lenin and Trotzky, and according to documents released in 2009 he had been recruited by MI6 as a spy, while allegedly being more of a go-between, if not a double agent playing off both sides against each other. One chapter in the report is entitled Propaganda trains, and it starts like this:

When I crossed the Russian front in October, 1919, the first thing I noticed in peasants' cottages, in the villages, in the little town where I took the railway to Moscow, in every railway station along the line, was the elaborate pictorial propaganda concerned with the war. [...] There were posters illustrating the treatment of the peasants by the Whites; posters against desertion, posters illustrating the Russian struggle against the rest of the world, showing a workman, a peasant, a sailor and a soldier fighting in self-defense against an enormous Capitalistic Hydra. There were also –and this I took as a sign of what might be – posters encouraging the sowing of corn, and posters explaining in simple pictures improved methods of agriculture. Our own recruiting propaganda during the war, good as that was, was never developed to such a point of excellence, and knowing the general slowness with which the Russian centre reacts on its periphery, I was amazed not only at the actual posters, but at their efficient distribution thus far from Moscow.

Ransome goes on to vividly describes the logistics behind this efficient distribution – the propaganda trains:

Russia, for purposes of this internal propaganda, is divided into five sections, and each section has its own train, prepared for the particular political needs of the section it serves, bearing its own name, carrying its regular crew – a propaganda unit, as corporate as the crew of a ship. The five trains at present in existence are the “Lenin,” the “Sverdlov,” the “October Revolution,” the “Red East,” which is now in Turkestan, and the “Red Cossack,” which, ready to start for Rostov and the Don, was standing, in the sidings at the Kursk station, together with the “Lenin,” returned for refitting and painting. [...] One wagon contains a wireless telegraphy station capable of receiving news from such distant stations as those of Carnarvon or Lyons. Another is fitted up as a newspaper office, with a mechanical press capable of printing an edition of fifteen thousand daily. [...] There is a special hole cut in the side of the wagon, and through this the kinematograph throws its picture on the great screen outside, so that several thousands can see it at once. [...] I doubt if a more effective instrument of propaganda has ever been devised.

Again there is no mention of a “Locomotive of History”, and again that absence can be accounted for with explanations given by Turowski: at the time of Ransome writing, the train was still only in planning stage. However, if Ransome was so close with the likes of Lenin and Trotzky as is generally assumed, wouldn't he have gotten wind of such a project and would have found it worth mentioning, given that this would have been the first propaganda train to be sent not only to the five sections of Russia, but to the West? Or is it that the alleged double agent Ransome precisely held back any ruminations along these lines for purposes of secrecy?

I feel increasingly enmeshed by layers of lack, absence, secrecy. And doubt. And one-eyedness. It doesn’t help matters that Turowski himself actively sows the seeds of doubt. Starting with the piece he contributed to the 1994 catalogue; here, he talks about the question of how 19th century scientific theories of binocular, stereoscopic vision and the understanding of art history – in the vein of John Ruskin – as a progressive thrust towards visual truth mentally prepared the discursive landscape for Strzemiński's particular utopian vision of fully developed visual awareness, and of painting as a purely visional experience – a utopia maybe not least borne out of Strzemiński himself having lost, due to an injury he suffered during World War I, sight on his left eye. As Turowski suggests, this one-eyedness tragically mirrors a Modernist discourse seeking to “ensure the triumph of the mind’s organizational functions over indeterminate instincts.” “The corporeality of physiological vision,” he goes on to argue, “fascinating in its purity, was defeated by the Cyclopean eye of the mind imposing a human order upon the disorder of nature. The utopias of Modernism were both its strength and its weakness. About Strzemiński’s utopias I have written often, and may do so again.” And so he has done, approaching the issue of the strength and weaknesses of Modernism in terms of looking at efforts of writing and propagating Modernism's own history. In The Locomotive of History, Turowski clearly makes numerous allusions that allow you to think that the status of truth in this whole matter is a contested one, at least as contested – and fascinating – as the cyclopean vision preparing us for a stereoscopic utopia.

Anna Baumgart, „Conquerors of the SunZdobywcy słońca”, 2012, film still, courtesy of lokal_30 WARSAW

Anna Baumgart, „Conquerors of the SunZdobywcy słońca”, 2012, film still, courtesy of lokal_30 WARSAW

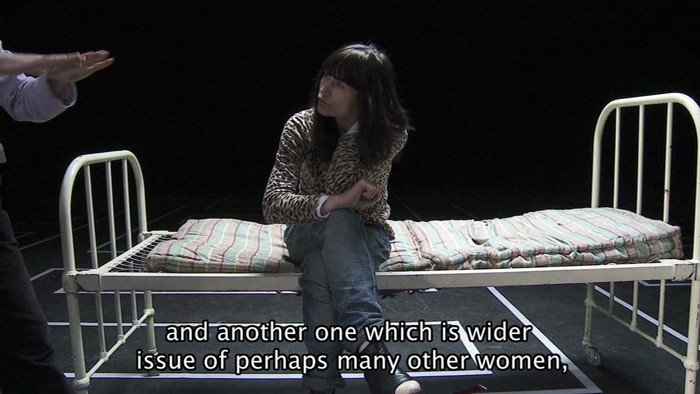

In a somewhat similar vein, in previous artworks and films, Anna Baumgart has appropriated existing media productions, “perverting” them to her own artistic ends. In the video series True? of 2001, Anna Baumgart inserted her own image into classical films of the socialist era, such as the Russian war movie The Cranes Are Flying (1957) by Michail Kalatozov, which tells the tragic story of a woman whose fiancée dies in WWII without her knowing while at home she is forced into an unhappy marriage thinking her loved one is still alive; or the Polish comedy Teddy Bear of 1980, directed by Stanislaw Bareja, which is a hilarious tale about absurd bureaucracy and black market economy in the late-socialist state. Baumgart literally enters these fictional scenarios to confront the factual realities and truth claims they enwrap – for example their claims about female behavior, as impersonated by the female lead roles – charging the ideological role models of cultural production with personal, feminist investment. In her video Fresh Cherries of 2010, it seems as if it is exactly the other way round: a factual reality and the historical truths it has produced are entered from the vantage point of a fictional scenario. A young actress tries to enter the roles of women forced into prostitution in Auschwitz, while a director, standing in the actual concentration camp’s crematorium, says: “The most important thing for me is that it should look good” (he is impersonated by the real-life director and screenwriter Marcin Koszałka); like Locomotive of History, the film includes historic footage, in this case for example of women being publicly stigmatized as whores, with signs around their neck and their heads shaved. In Locomotive of History, similarly to Fresh Cherries, historic reality is confronted with the contradictory dream reality of artistic production, its aspirations, failures and traumatic kernels.

But to be clear, Turowski and Baumgart are not lazily messing around with historical fact. Turowski's book, with all its footnotes and critical mass of historical detail, is clearly written from an expert’s point of view. However, the first short chapter telling the story of how he first met the person who would give him the secret papers bears the title The poetics of history and the trouble with fiction, and a few pages on he states that “the material clues or perhaps just literary inventions that emerged from the documents became a critical method that could be applied both to a historical reality thus reconstructed on the basis of facts, and to fictional narratives based on this reality.” Turowski employs the language of fictionalization when he headlines a chapter The action moves to Warsaw, ironically playing on the language of the kinds of documentaries that are shown on history channel: presented with the authority of authenticity, with booming voices and drum rolls, while aping the narrative shape of fiction films, promising indeed suspense and action rather than cool-headed analysis. That said, Turowski also continuously quotes from sources that – counter to the ominous secret papers wrapped in newspaper – are publicly accessible and prove not only his expertise but also his scientific research efforts, from an El Lissitzky letter to Malevich held in the archive of Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum to Interior Ministry papers of the 1920 Polish government held in Warsaw’s Archivum Akt Nowych.

Nevertheless towards the end of the book, Turowski uses a kind of parable to illustrate his point about the contested status of truth in regard to the historical reality of Malevich's and Strzemiński's modernist endeavours and utopian visions; the parable tells the story of the tyrant of an African state who escapes being hung by rebels, as his body is being replaced by that of an insurgent who had accidentally been killed; being brought to an island by arms traders, he strikes up a conversation with the captain of the boat, who says the “historical truth” is that he was dead, whereas “you being alive is the physical truth... [...] Historical truths are caused by some events in the future...” In other words: it is only in retrospect that we arrive at a certain version of historical reality that is agreed upon to be truthful, in a process in which scientific discourse and political manipulation usually become hopelessly intermingled.

Anna Baumgart, Conquerors of the Sun,

Anna Baumgart, Conquerors of the Sun,

Andrzej Turowski, The Locomotive of HistoryThe crucial question hence is whether this retrospective interpretation is meant to ward off alternative readings and keep the power structure in tact – or whether it, on the contrary, is meant to unleash previously ignored counter-stories and readings. Turowski goes on to state that in his tale, the train is “the lost truth of future history which once drifted among the imaginary islands of modern Utopias.” In other words, the point is not to claim that the train – counter to the Łódź Museum of Modern Art co-founded by Strzemiński – ever existed as a “physical truth”, but that indeed it is an embodiment of the actual Suprematist and Unist ambitions and failures, the desire for a better society based on aesthetic education, diverted and sent to nowhere – just like the train – by political intrigue and blunt aesthetic functionalism. The point is that these utopian dreams did exist – yet by nature of them being dreams they can never be claimed as “physical truth”. Turowski’s and Baumgart’s endeavour is ultimately to honour the importance of these dreams, not least with a view to our current reality, from the disappointment with the Occupy movement’s lack of purpose and structure to frustration with Artur Żmijewski's impotent attempts to jolt art into political action (as exemplified by his Berlin Biennale 2012), which keeps bringing us back to the dilemma of the Left: dissent, self-reflection and the emancipatory possibility of doubt is arguably what fundamentally distinguishes the political Left from Fascism, which is all about trans-historical essence of blood and soil, personality cult, and the demand for unquestionable authority – but it is precisely these qualities that makes the Left feel impotent in the face of getting things done on a grand scale, of mastering difficult situations, of exerting discipline to do so, finally making it attractive precisely to flirt with the notions of trans-historical essence, personality cult, and unquestionable authority. So the “intimate yell” of Mayakovsky is still ringing in our ears, reminding us that the conundrum of artistic doubt and creativity versus political discipline and violence remains unsolved.

So what exactly are Turowski and Baumgart doing with their joint project? To come to an answer, we need to look at the underlying questions concerning the status of truth in regard to works of art, and fiction. In recent years, there have been numerous discussions in different fields – in art, film, theatre, literature, etc. – around the same underlying concern: a discontent with the conventions of fiction-making vis-à-vis social reality and historical fact. In literature, this discussion has maybe been lead most pronouncedly. The American writer David Shields published an anti-novelistic manifesto entitled Reality Hunger (2010), in which he expressed a fundamental impatience with literary convention, with sending fictional characters through fictional scenarios, and praised the literary incorporation of unprocessed, found sources, of essayist hybrids in the realm of storytelling. Shields diagnosed an underlying urge of our contemporary culture – characterised by reality-TV formats, facebook confessionalism, and not least fake memoirs and plagiarised novels – to somehow reach back (or at least pretend to be able to reach back) to what seems to be a thing of the past: direct access to profound first-hand experiences, and to art having real impact. The dilemma is of course that there is no resort really to “authentic reality” – that we get hopelessly enmeshed in contradictions if we pretend to have direct access to it.

In literature, the postmodern cure for that dilemma prescribes ironic aloofness, switching sovereignly between a Warholian copying and scanning of actual documents of banality (say, emails, news bits and fragments of informal conversations) and sarcastic, punchline-driven comments on these very findings. However, this postmodern cure – because of its pretense to stand above banality, only occasionally softened by self-effacing humour – quickly loses its allure; writers then have to face the fact that the attempt to turn “actual” social experiences and historical occurrences into story not only inevitably produces contradiction, but that one needs to immerse oneself in these very contradictions (it is this immersion into contradiction and the self-reflective awareness of the necessarily hybrid nature of literary material between being found and fabricated that David Shields seems to be after).

In other words, rather than sending fictional characters through fictional scenarios, one may as a rule rather send real-life characters through made-up scenarios – or made-up characters through real-life scenarios (or in fact create complicated mix-ups between these two options). “Sending through” however would be misleading, for this would not be the sovereign act of a god-like author, in the vein of a scientist sending a laboratory mouse through the maze. Because in that case, another pretension would come into play: that what is supposedly an experiment to gain true insight is in fact so controlled that the outcome is prescribed. Instead, that author would rather have to implicate themselves into that experiment, allow her- or himself to be co-immersed, to lose control over the scenario in order to gain some sense of control over the validity of its aesthetic outcome. Or to put it in Freudian terms: the point is to allow the super-ego to trip over the workings of the unconscious, so that the ego gets a chance to slip out of the terrible mess thus produced and beautifully reflect on it. This exercise implies that the unforeseen may happen, and that glitches and hick-ups are to be welcomed – for it is precisely in these unforeseen glitches and hick-ups that “reality” resides, unprocessed yet by memory and attempts to realign them into the “official” story.

It is precisely such glitches that Turowski and Baumgart, in the book and film respectively, present as the events that allow the story to be told about the Russian revolutionary avant-garde of the 1910s and '20s to unfold. The first one testifies to the often absurd logic of a society where information itself is tightly governed by the late Soviet state:

When I was studying revolutionary history in the famous library of Moscow’s Lomonosov University, I got used to being refused access to the majority of documents. One day, however, I was surprised and even a little alarmed to find that, having submitted fresh requests, everything that had hitherto been denied me started being brought out from the cavernous storerooms. It soon turned out that this was not the wind of history blowing, but that someone had tried to let some fresh air into the musty manuscript and book depositories and a humble draught had blown notices displaying the single word “Nelzya” (Not Allowed) off the shelves.

The glitch that allows access to whatever is manifested in forbidden documents is merely a breeze, or rather: it is the mishap of whomever opened that window and subsequently had no clue where exactly to put back the notices that had been blown off, and the mishap of whomever then decided to not tell the superior and thus to perpetuate the temporary suspension of “Not Allowed”, until the glitch is discovered and the censors realign the parameters.

The second accidental event is of course the aforementioned incident of clandestinely held documents wrapped in newspaper being handed over in return for a bottle of whiskey. Again, it is about getting access to hitherto unaccessible documents. What all of this exemplifies – and as the film goes on to exemplify with the means of visual-narrative persuasion and suspense – is that we have encountered a shift in philology and historiography. Since the 19th century, one could argue, historians thrived to present us with a cleaned-up version of history, allowing us to see history's essence – to filter out who really were the deciding figures, which really where the triumphs and defeats that changed the course of history. With the advent of globalized information culture in the 21st century, however, this urge to present a clean, clarified vision of the past has been replaced by a fascination with its fuzzy outlines, its grey zones, the awareness of loopholes and gaps in our knowledge of the past, despite of our increasing access to sources. This paradigm shift does not mean that truth is suspended – rather on the contrary, by admitting the contradictory nature of our readings of the past, we come a little bit closer to truth. Often it is precisely the constellation in which staged scenarios are “tried out” on actual reality and vice versa that bring about an insight into what really is the fabric of what we are supposed to take for proven knowledge about the past. This is also the reason why fabrication and staging in relation to historical events is not an excuse for plagiarism, or for false confessional claims to absolute authentic experience as in the case of the numerous fake Holocaust memoirs, such as Herman Rosenblat’s Angel at the Fence (2009) or Binjamin Wilkomirski alias Bruno Dössekker’s Fragments: Memories of a Wartime Childhood (1995). Actual trauma – Rosenblat was indeed a survivor of Buchenwald, and Dössekker had been sent, as the illegitimate child of an unmarried mother, to a Swiss orphanage – here becomes the foil for a desire to be celebrated for a confession built on fragments from other confessions (for example, Rosenblat’s story of his future wife throwing him apples over Buchenwald's fence seems directly lifted from Art Spiegelman's Maus, in turn a testimony of an actual Holocaust survivor, Art’s father Vladek). The point is that the need to “embellish” the story with symbols and heart-wrenching anecdotes is a direct effect of a popular culture that is receptive to these trigger points of redemption, turning the unbearable horror of the Holocaust into a bearable, tear-jerking love story (Rosenblat and his wife where guests on Oprah Winfrey’s television show several times).

Anna Baumgart, Fresh Cherries, 2011, film still, courtesy of lokal_30 WARSAW

Anna Baumgart, Fresh Cherries, 2011, film still, courtesy of lokal_30 WARSAW

Not mentioning, lest making accessible the sources from which one appropriates inevitably produces curiosity. Postmodern thought and writing thrives on this curiosity: even if it pretends to praise a kind of anarchist ideal of uncredited appropriation, it still thrives on the aura and authority of much of what it appropriates, while at the same time claiming to deflate that very aura and authority – say, a postmodern writer who mixes uncredited Kafka quotes with lists from his last visit to the supermarket, with dialogue from Godard, also uncredited. What we have here then is a postmodern version of modernist mysticism: the Modernists did not necessarily appropriate – you could say: steel – less than the Postmodernists, but the difference was that whatever they stole was arguably unknown to a wider audience, so it was easier to pass it for an invention of genius out of nothing (think for example of the ancient Iberian stone heads that had literally been stolen from the Louvre and then acquired by Picasso, and which inspired him to paint Gertrude Stein's head in 1906 in a simplified, planar manner).

The postmodernist can’t pretend anymore that his work comes out of nothing – his audience knows too much already – so it’s rather about a game of sophistication: yes, I “stole” things to make things, but can you recognise what I stole, and where from? In our current age – some call it metamodern – we are beyond that stage as well: with smartphones allowing instant access to the endless Internet archive, even the gesture of sophistication seems dated – you just type “Picasso stole” into a search engine and you’ll come across something eventually. So what young artists these days often do is either dramatically increasing the number of sources they tap into, and accelerating the pace at which they do so (I have called that phenomenon “super-hybridity”), or they hover midway between the Modernist and Postmodern position: some references they keep secret, some they display openly, feeding on the aura of what they refer to.

I think Turowski and Baumgart offer us yet another, possibly more rewarding model: like in Postmodernism, they operate with the curiosity caused by inaccessible sources, but they remain inaccessible, for most of us, because they are either literally hard to access (some archive in Amsterdam or Warsaw) – or might in fact be invented. At the same time though, what they put forth is based on actual, thorough research into existing, confirmed sources – from the writings of Strzemiński to authentic historic film footage. Our curiosity is roused, not allayed, if we learn that some of these sources might in fact be invented. In other words, rather than numbing our awareness of history with mystical tabula rasa gestures à la Modernism, or the historical indifference of Postmodern eclecticism, Turowski/Baumgart provoke a reconsideration of actual history precisely by doctoring it. Maybe, again, the term Metamodernism might apply for this.

What could have become of the Suprematism and Unism as models of aesthetic education in a politically revolutionary environment, if they hadn’t been sidelined by Proletkult, the agit-prop understanding of art as a mere vessel of a political message, and Bolshevik hardliners? Or one step further: could the political revolution of the 1920s, still taking our sensory apparatus for granted and understanding art merely as a tool, have been combined with the revolution of the senses of the late 1960s, the “mind-expanding” audio-visual, sensual-sexual experiences of the hippie generation? Of course that dream has been dreamt by many, often with disenchanting results, from brainwashing sectarian tendencies to the excesses of drug and sexual abuse. Nevertheless, the dream continues. Could art attain true political impact, but on art’s own terms?

When Bob Dylan was asked recently why a 14 minute song on the sinking of the Titanic – another grand event of the 1910s – for his latest album Tempest (2012) included ruminations that divert from known facts, or are based on James Cameron’s 1997 movie rather than the actual historical event, he answered: “A songwriter doesn’t care about what’s truthful. What he cares about is what should’ve happened, what could’ve happened. That’s its own kind of truth."

In other words, what songwriters, as well as artist, filmmakers, or writers, are after is an idealized truth of what should or could be. It is that very impulse that explains why there is a song to be written, a story to be told, a film to be made, in which Strzemiński, Malevich and all the other forward-thinking dreamers of Russian and Polish abstraction enter political history to an even greater degree than they actually did, in order to do justice to their achievements precisely in the face of the undeniable reality of them having been sidelined, just like that train, by the ruling powers.

Anna Baumgart, Fresh Cherries, 2011, film still, courtesy of lokal_30 WARSAW

Anna Baumgart, Fresh Cherries, 2011, film still, courtesy of lokal_30 WARSAW