“Indeed Daas is hidden among the Sephiroth and stands to the side; (…) to that place to which I wanted to lead you no man has ever been from the beginning of the world.”

“Know this, that we go now to the holy Daas, about which you do not know, there to serve God; therefore be careful of my teachings. There also will be a certain woman, a God-fearing one, whole with God and people, and I will establish her over those women who were called Sisters. She, similarly, will give them teachings (…). Beforehand, before this time comes, I will order the whole Company that there be no mention of the names Brothers and Sisters. All these deeds which he will teach you, they are conduct proper to royal authority. Indeed, I have told you that I am a flaming bush which does not burn up, for I was a thorn in the eyes of all who saw me.”

— Jacob Frank

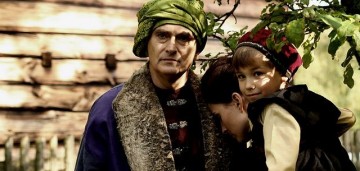

Daas, dir. Adrian Panek, Poland 2011

Daas, dir. Adrian Panek, Poland 2011

In theatres 7 OctoberPlagued for over a decade by a curse of historical films aspiring to the title of “masterpieces”, Polish cinema has once again been put to the test of yet another belligerent national premiere. This one isn’t about mourning defeats and those who fell on the battlefield, but about glorifying the “miracle” that occurred “at the Vistula”, when, during the Polish-Bolshevik Battle of Warsaw, we successfully turned back the tide of the “revolution”.

Almost in parallel, Polish viewers were confronted with the debut film by Adrian Panek, Daas, which, rumour has it, was one of the two “incomprehensible” films screened at this year’s Polish Film Festival in Gdynia. Critics complained about the “weird scenes” and the sheer number of plot lines, adding that it was historically jumbled, unreal, and intellectually heavy. One respected film journalist put it in blunter terms, asking directly: “What is this film even about?!”.

To be fair, it is never fully explained to the viewer what the titular “Daas” actually is. Only during the opening minutes does the director attempt — through the use of footnotes — to introduce the audience to the cultural and historical context of the era, which, in any case, only serves as a backdrop for the story. The literature on 17th and 18th century Jewish mysticism is a good source of information about the genesis of the events, but is hardly required reading for those wishing to understand and relate to the film in some way.

Daas: A Review

from Gdynia

Adrian Pank’s Daas was the most surprising — and in my opinion, best — picture screened at the Polish Film Festival in Gdynia. This was the movie that should have won the Golden Lions. First of all, it deserved them. Second, they might have won Daas some publicity. Whether or not Pank’s debut will even find a distributor is an open question. Let’s hope for the best. Everything about Daas is intriguing: the persona of the 18th century false Jewish messiah Jacob Frank; the clash of three orders: religion, politics, and science; the mind of the mystic, rationalist, and cynic; the historical depiction; and the narration, which mixes temporal structure and employs ellipsis and understatement. Critics complained that it was hard to figure out what was going on in the film. But isn’t that precisely its greatest quality? Polish films are often obvious from the very start — what’s the point in even watching them? To remind ourselves how important family is, how horrible loneliness can be, and how difficult it sometimes is to accept our past? In Daas, an investigation of Frank conducted simultaneously by an imperial civil servant and a former disciple ends in the downfall of the false messiah’s. The emperor enters the picture, laughing in the face of the mystics, alchemists, and all those whose ethos drives them to serve their country. Cursed questions are ridiculed, the chase for something that would change the world loses its meaning, and honesty becomes impossible. Panek, in effect, tells the story of the failure suffered by every project in which the modern world had any faith, and the dawn of an era of cynical reason and all its mutations prefixed by the word “post-” (by which I don’t mean “postmodernism”).

Jakub Socha

Panek’s film is an excellent example of the shift in our understanding of historical films, once associated with “heavy” period pieces. The debut filmmaker opted for the “new historical cinema” route, exploring other, uncharted versions of Polish history; he attempts to spring back into modern times and — crucially — avoids the stereotypical depictions of 18th century post-partition Poland that we’ve all seen hundreds of times.

The two main characters in Daas are Jakub Goliński (Andrzej Chyra) and attorney Henryk Klein (Mariusz Bonaszewski). Goliński files a complaint against a mysterious healer and self-proclaimed prophet and messiah Jacob Frank (Olgierd Łukaszewicz), who talked Goliński into abandoning Judaism and converting to the Catholic faith, robbing the man once he had disowned his master. Klein receives the complaint in Vienna and attempts to solve the mystery of Frank, whose position in the imperial court is unquestionable. Meanwhile, he must also try to save his wife (Ditta Berkeley), who has lost all contact with reality following a stroke. Both meet at the very end of the story to start a new life together in a completely different reality, one in which mysticism has ceased to have any meaning.

A False Messiah

Daas is the true “Holy Religion of Edom” — divine revelation hidden under the institutional shell of Catholicism. Like Sabbatai Zevi and Osman Baba before him, Jacob Frank proclaimed himself the Jewish messiah in the mid–18th century, claiming to be the one awaited by generations of Jews living in “exile”.

The first modern-day messianic tendencies among European Jews began in the mid–17th century, around the time of Khmelnitsky’s Cossack Uprising. Jewish pogroms and widespread fear led to popular belief in the imminent end of the world. It was then that the Kabbalist Sabbatai Zevi appeared, a man who, in 1648, “uttered the name of God”, thus doing the impossible (according to tradition) and proclaiming himself the messiah. Jewish masses were moved by the belief that 1666 would bring salvation to all. Captured by the sultan, Sabbatai was forced to convert to Islam, giving rise to the doctrine of “purification through transgression”, according to which the path to salvation led through the sinful conversion of the messiah and his disciples.

Jacob Frank initially also claimed to be the incarnation of divine revelation, adopting the so-called practice of the “clandestine walk”. Teaching small groups of believers, most of whom were former Sabbataians, Frank incorporated elements of other religions, particularly Catholicism, from which he borrowed the Holy Trinity. His teaching soon included the concept of conversion to Catholicism, which he claimed would guarantee his followers eternal life on earth. According to Frank’s ever-evolving doctrine, earthly and divine salvation would occur simultaneously through the messiah. The “Jewish messiah” left his mark in Polish history thanks to two religious debates, one in Kamieniec (1757) and the other in Lviv (1759). Both events resulted in clashes between Talmudists — followers of traditional Judaism — and Frankists, followers of the mystical book of Zohar. By that time, Frank’s doctrine had already begun to encourage antinomic practices such as the open flouting of religious law and insulting the guardians of Jewish tradition. The ritual burning the of Talmud accompanied by mad dancing depicted in Daas is a direct reference to this period, one in which the rejection of Jewish tradition was consistent with Frankist teachings about salvation.

The debate in Lviv ended with Frank’s conversion to Catholicism, witnessed by members of the Polish nobility. Frank’s godfather was King Augustus III. In Daas, the wealthy szlachta and their role in “converting the infidels” is referenced in one scene in which a princess (Danuta Stenka) bestows land on her “godson” Goliński. The princess’s remarks about contemporary Polish society express the true goals of Polish Catholics, who wished to convert the greatest possible number of Jews at any cost.

From the Frankist perspective, conversion was regarded as more than just one stage on the path to salvation, but it also set the sect apart from Jewish tradition, uniting its followers around their leader. So great was the hatred toward the Talmud espoused by Frank’s disciples that at the Lviv debate the anti-Talmudists stated openly: “the Talmud teaches that Jews need Christian blood, and whoever believes in the Talmud is bound to use it.” This point marks the severing of the ties between the Frankists and the Jewish rabbis. According to Frank’s doctrine, each of the three religions were to be practiced in succession, together with the messiah, as individual stages on the path to salvation.

Shekhinah

Frank’s authority entered a period of crisis when the self-proclaimed messiah was arrested and held in the Jasna Góra monastery. One of the reasons for the mystic’s arrest was his claim to be the incarnation of Jesus Christ, an assertion that the Catholic clergy in Poland was unable to accept. It was likely then that people’s perception of Frank underwent a certain change. No longer seen as the messiah, Frank was now regarded as a leader who called himself a “simpleton”, remained close to his people, and was merely predestined to fulfill his messianic mission. During his stay at Jasna Góra, Frank began incorporating Marian elements into the doctrine of his sect. According to his new teaching, the image of the Black Madonna held the hidden Shekhinah — the feminine divine emanation that would be released by the messiah, bringing salvation.

The female roles in Daas are illusory and understated. Klein’s wife, who suffers a stroke, become a silent visual leitmotif of the film. Her presence is only marked by her body, a “prison for her soul”, similar to the prison in the image, from which Frank was to release the mystical Shekhinah. A similar resolution is used for the plot involving the wife of main character Jakub Goliński, a historical figure who accompanied the Frank court until its stay in Brno. In one of the opening scenes, Golińska (Magdalena Czerwińska) bares her bosom before the congregation. Each member of the sect kisses the woman’s breast. Such rituals were typically practiced by Frankists and were intended as a demonstration of antinomy — the rejection of Jewish tradition — and imminent salvation through sin. According to Frankist doctrine, sexual acts also had a mystical meaning. Golińska abandons her husband to have sex with other followers. As Jan Doktór explains, “Frank likely preserved the ceremonial sexual practices because they were in line with his temperament. We also cannot completely reject Kraushar’s proposal that such practices served to weaken marital bonds, which stood in the way of the followers’ complete submission to the will of the messiah.”

The imperial court

Frank resided in Vienna in 1775–1776. Daas depicts an encounter between Emperor Joseph II and Eva Frank, who led the sect at the Offenbach court after the death of her father, and in whom the emperor took an interest. According to an account by Alexander Kraushar, the thirty-year-old widower emperor was “sensitive by nature and submissive towards women, in whom he found respite from the toils of his life as a monarch.” In Daas, the emperor succumbs to the charm of Eva, who was being groomed to be his next wife. Eva makes several appearances in the film, each of them fleeting, as if she were keeping some secret. According to Frankist philosophy, Eva left Jasna Góra with a piece of the divine Shekhinah within her, waiting to be released. It is here that the political dimension of the Frankists is revealed, weaving into the plot to stage a violent coup against the emperor. In reality, wherever Frank was, he would try to form a closed, self-sufficient community limited to his court of followers and a military unit. The scene depicting a demonstration put on by a “healer” in a Viennese park played on the locals’ fascination with sect’s mysticism and grandeur in an effort to win public acceptance.

Emancipation and assimilation

In one of the closing scenes, Jakub Goliński, now without a penny to his name, decides to leave Europe and head for South America, wishing to put his past behind him. He stands at the shore with attorney Klein, waiting for an approaching ship on the horizon. Frank, now disgraced in the eyes of both main characters, embodied rebellion against Jewish tradition within its ranks. As Doktór explains, “Cut off from European philosophy, the Frankist rebellion could only refer to traditional religious imagery. (…) Following their abandonment of Judaism and the death of their messiah [Jacob Frank died in 1791 — J.O.], they had no choice but to seek support in European culture. A rebellion within the ranks of a tradition that was their only model of thinking and acting had to end in defeat, departure from the tradition, and assimilation.”¹ Panek’s main characters exemplify this sort of assimilation, literally running away from Jewish mysticism, courtly intrigue, and mystery.

Frankists managed to survive the 1816 death of Eva Frank and had a profound impact on the Jewish Enlightenment, or Haskalah. For part of Frank’s 19th and 20th century followers, they remained a symbol of spiritual and political liberation, “the first freedom fighters in the ghetto” (Gottlieb Wehle, quoted by J. Doktór).

¹ Doktór, Jan. Jakub Frank i jego nauka. Na tle kryzysu religijnego tradycji osiemnastowiecznego żydostwa polskiego (Jacob Frank, his Teachings, and the Crisis of Religious Tradition among 18th Century Polish Jewry).