Sound and Vision is based in Hilversum, half an hour from Amsterdam. An army of people employed at the Media Park pours out from the train onto the platform. It’s a town of broadcasters: television stations, production studios, press agencies. Several times larger than the Polish Public Television complex at Woronicza Street. The area quickly absorbs the swarms of approaching worker bees.

Sound and Vision, photo: A. Słodownik

Sound and Vision, photo: A. Słodownik

I walk up to the colourful cube. Its façade resembles a stained glass window of television screen images. Non-still, and therefore blurry. It turns out upon entrance that the part visible from the outside is just half of the whole building. The other half is tucked away underground. The design becomes apparent once you discover the internal light well in the middle of the edifice, which nevertheless looks nothing like a traditional city-centre townhouse.

Although located a bit outside the city itself, Sound & Vision can’t complain about a lack of visitors. According to one anecdote, the Dutch radio pioneer Willem Vogt planned to move from Hilversum to Amsterdam but his wife objected, fearing she would have to give up her housemaid. This event supposedly lay the foundations for the present location of the Media Park. The first guests begin to filter in at 9:30. Level -1 hosts a group of students learning to draw, sketching cubical irregularities. The depth of the well is 18 meters, a full five floors.

Sound and Vision

Nederlands Instituut voor Beeld en Geluid is an archiving institution for Dutch public broadcasters. It stores documentary films and radio programmes: news, speeches by the Royal Family, nature films, and sporting events.

The walls are covered in renderings of pixels (or are they contemporary atoms?). There are tiles with web-2.0-like rounded corners adorned with characteristic asterisk icons. As lifted from the visual code of computer systems. There are semi-transparent photos of Dutch television personas. Metallic colours broken with vivid orange – the national colour of the Netherlands. 3’12”, 9’12”, 2h – the time marked above every window in the well tells us how much time is needed to obtain materials from the given archive.

“It’s more an artistic vision rather than hard data backed by research,” says Consumer Department Manager Michel Hommel.

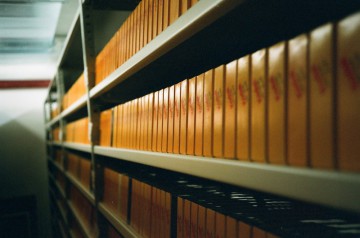

Goodies, photo: A. SłodownikI’m here on a study visit. Mr. Hommel leads me to one of the underground archives. I expect hundreds of shelves laden with tapes, celluloid, and VHS. Yet they sag under a different kind of weight: old record players, radio sets, 8-track cartridge recorders. Philips, JVC, SABA, Braun. I leave the gramophones and tuners behind and move on. The tapes are stored elsewhere. I am not counting the racks, but it would take more fingers than I have on one hand. Suddenly racks upon racks of yellow appear before my eyes, unfolding like a carpet: KODAK video tape covers. Every rack has a wheel that lets it be moved and steered around the precious space.

Goodies, photo: A. SłodownikI’m here on a study visit. Mr. Hommel leads me to one of the underground archives. I expect hundreds of shelves laden with tapes, celluloid, and VHS. Yet they sag under a different kind of weight: old record players, radio sets, 8-track cartridge recorders. Philips, JVC, SABA, Braun. I leave the gramophones and tuners behind and move on. The tapes are stored elsewhere. I am not counting the racks, but it would take more fingers than I have on one hand. Suddenly racks upon racks of yellow appear before my eyes, unfolding like a carpet: KODAK video tape covers. Every rack has a wheel that lets it be moved and steered around the precious space.

Racks upon racks, photo: A. Słodownik

Racks upon racks, photo: A. Słodownik

One could browse the archives for ages. It’s time to see what’s above ground in a space referred to as neither a “museum” nor an “exhibition”. I follow a high spirited group of fifty-somethings making their way to “Experience”. Before I get there, I pass by editing and digitisation studios. Editing tables, spools for old tapes. One of the studios has been taken over by a group of youngsters filming an interview with a someone whose youth has long passed. Then there is a “box in a box”. It is a studio tailored to the needs of whatever television programme it currently serves. This one imitates a pub with all its attributes: tables, bar, stools, and glasses. But instead of alcoholic beverages in bottles, the shelves contain “TOP 2000 PLATENKAST” – an impressive record collection.

Time for „Experience”. Mired in darkness, the fifth floor buzzes with with numerous neon signs, displays, screens, and spotlights. One big television studio, with radio accents.

First up is Top Pop. Familiar to everyone in the Netherlands. I see a stage and an auditorium. A screen on one side is playing an original performance by the artist as a warm-up. After you refresh your childhood or adulthood memories, you are ready to go on stage yourself. Those accompanying you get to pick one of several roles offered by the studio: audience members, light technician, or a producer who mixes the image of the star in real-time on a yet another screen that splits to sub-parts. Playing on a plastic guitar and nostalgia. In England Top Pop would most likely be replaced by Top of the Pops. In Poland – the stage of the Sopot International Song Festival.

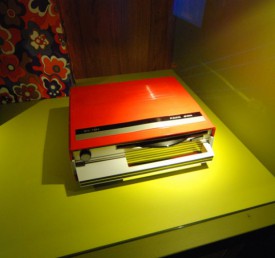

Time travel, photo: A. SłodownikMoving on, I pass by a mini-exhibition of record players displayed on a bright green and flowery shelf. The theme: the 1970s. These finds must come from the archive I visited earlier on. They are exceptionally attractive objects, especially when they’re unexpected.

Time travel, photo: A. SłodownikMoving on, I pass by a mini-exhibition of record players displayed on a bright green and flowery shelf. The theme: the 1970s. These finds must come from the archive I visited earlier on. They are exceptionally attractive objects, especially when they’re unexpected.

The archaic devices make me aware of the existence of a time scale. First there was writing, then print, and then tape. Communication has been harnessed in a variety of forms. Digitisation did not come from nowhere.

Another space to „Experience”: radio studio. A basic model. The photo wallpaper depicts a shelf stocked with vinyl records. Slightly out of scale, but no one minds. Here you can listen to a recording chosen in advance, or record your own voice. Guests receive all their “Experience” recordings straight to their e-mail inbox after they leave.

Blue is green, photo: A. SłodownikThe blue box is green. I sit by a desk fitted with a screen and a microphone in front of two other screens. The one on the left shows headlines from a Dutch news programme (I suppose). I appear on the screen in no time. The green spill behind my back is transformed into orange zigzags. The top right corner displays archival black and white footage. In the meantime, the screen on the right (with a contrast-protection hood) goes “Niet eerder maakte de mobiele eenheid zo’n smerige ontruiming...”. I read with very little understanding. I read whatever the yellow buttons point at directing my speed. I this manner, I became a Dutch news anchor for five minutes. I guess, in my case, reading Polish news from, say, 1989 would be more thrilling, but this exercise does the job.

Blue is green, photo: A. SłodownikThe blue box is green. I sit by a desk fitted with a screen and a microphone in front of two other screens. The one on the left shows headlines from a Dutch news programme (I suppose). I appear on the screen in no time. The green spill behind my back is transformed into orange zigzags. The top right corner displays archival black and white footage. In the meantime, the screen on the right (with a contrast-protection hood) goes “Niet eerder maakte de mobiele eenheid zo’n smerige ontruiming...”. I read with very little understanding. I read whatever the yellow buttons point at directing my speed. I this manner, I became a Dutch news anchor for five minutes. I guess, in my case, reading Polish news from, say, 1989 would be more thrilling, but this exercise does the job.

Where am I now? The flash animation on the S&V website serves as a better landmark. The film shows the decades from 1930 to “Heden” – now. Every decade has its particular style expressed by a properly adjusted female model in front of audio and film players. You click to get a film, audio recording, or photographic material from the given period. The 1930s is silent films, “Heden” shows a computer linking to the Institute’s YouTube channel. In “Experience” we really enter the decade: every era has its exhibition pane and a comfortable watch-and-listen sofa. We are in a user friendly archive.

“Experience” is not just about nostalgia. For a moment, every would-be TV star has a chance to shine in the limelight. I enter the changing room, complete with vanity mirror. The wallpaper consists of images of polaroids – photos of initial hair style and make-up. I still have time to freshen up before the countdown. 10, 9...3, 2, 1. The doors slide open, I go out, one camera rolls towards me on a dolly, another one spins around, invisible hands clap, reflectors dazzle and cast pink stars onto my face. You can savour your five minutes of fame moment even longer by posting the recording online.

The cafe, photo: A. SłodownikI finally “exit through the gift shop”. Mouse pads, bags, mugs, pencils, all covered with the control signal pattern (the wall in the Institute’s cafe also displays this archetypical sign). Other gadgets seem reminiscent of the building’s façade. I find a clock shaped like a vinyl LP and a few other radio gadgets. Classic.

The cafe, photo: A. SłodownikI finally “exit through the gift shop”. Mouse pads, bags, mugs, pencils, all covered with the control signal pattern (the wall in the Institute’s cafe also displays this archetypical sign). Other gadgets seem reminiscent of the building’s façade. I find a clock shaped like a vinyl LP and a few other radio gadgets. Classic.

The part of Sound and Vision open to the public employs radio and television clichés. It is an easily absorbed essence of the entertaining part of those worlds. Or at least how we imagine it. A balance to the authority of the underground archives. Far removed from any analytic goals. It is a TV and radio Disneyland.

The study visit comes with a series of meetings with heads of the Institute’s departments: research, education, digitisation, access. A broad spectrum of issues seem to meet in few points, but single one seems to prevail over the others: no content without context. The subject matter does not exist without its frame of reference.