As usual

There are those who own very few things. Frequent packing requires that they constantly filter their material possessions and question their own needs. Such is the life of the “Runner”. One such Runner, a bookworm since his early years, recently purchased an e-reader, beating his gadget-loving father to it. For the past week, the Runner has been telling anyone who will listen about the statistics of his virtual bookshelves. The titles in his library are largely in English. Any lexical confusion is quickly dispelled by a pop-up dictionary, the Runner enthusiastically explains. He still reads, but he is no longer burdened by the weight of his books, luggage overage fees, or overseas shipping costs.

At the other end of the scale there is the stationary reader. Ever since the bookshelves went up in his apartment, his cognitive pursuits have had to adapt. Mini-towers of mixed books gathering dust on random pieces of furniture have been sorted according to a number of criteria: size, genre, publisher, emotional bond, familiarity with the content, frequency of use, and books to be read in the future. The fact that each book belongs to several categories at once has forced the reader to reconsider his priorities and make life-altering decisions. (E-readers allow “Runners” to tag each book with several categories.) One more criterion: abandoned titles (bookshelf space is at a premium).

At the other end of the scale there is the stationary reader. Ever since the bookshelves went up in his apartment, his cognitive pursuits have had to adapt. Mini-towers of mixed books gathering dust on random pieces of furniture have been sorted according to a number of criteria: size, genre, publisher, emotional bond, familiarity with the content, frequency of use, and books to be read in the future. The fact that each book belongs to several categories at once has forced the reader to reconsider his priorities and make life-altering decisions. (E-readers allow “Runners” to tag each book with several categories.) One more criterion: abandoned titles (bookshelf space is at a premium).

Meanwhile, events in public transportation resemble photographs by André Kertész. There are newspapers (all those free commuter papers), but mostly novels, the kind featuring olive and porcelain-skinned people, blondes and brunettes, short and tall, working and retired. Thrillers are read with dilated pupils. An English textbook spirits a middle-aged woman out of the train, dropping her into the world of definite and indefinite articles. A young lady reads the daily paper, completely absorbed by the world news pages. A book with the words “politics” and “art” on the cover wrinkles the brow of a man in glasses. Another lady is occupied with a tabloid, the cover of which announces the details of a certain Polish celebrity’s sex life.

Reading rooms on rails, photo: A. Słodownik A bound stack of charts and reports has the full attention of an elegantly-dressed gentleman. Here a novel, there a novel: it seems that speaking would be an unforgivable faux-pas. Others clutch printouts of emails, articles from various websites, and newspaper advertisement inserts, or swap weekly magazines with the other passengers in the compartment. We arrive at my stop before I finish my chapter. No problem: reading while walking is no challenge at all. You just need to keep a slow pace. Reading rooms on rails flourish without the encouragement of cultural institutions.

Reading rooms on rails, photo: A. Słodownik A bound stack of charts and reports has the full attention of an elegantly-dressed gentleman. Here a novel, there a novel: it seems that speaking would be an unforgivable faux-pas. Others clutch printouts of emails, articles from various websites, and newspaper advertisement inserts, or swap weekly magazines with the other passengers in the compartment. We arrive at my stop before I finish my chapter. No problem: reading while walking is no challenge at all. You just need to keep a slow pace. Reading rooms on rails flourish without the encouragement of cultural institutions.

Rare views

A couple of adults spend a quite evening at home: one of them picks a book of the shelf. They log onto the couch and take turns reading aloud: short stories, fairy tales, and novels. Some parts are reread when the listener drifts off, or the reader loses her voice. They interrupt each other while reading. There is time for discussion and to explain doubts. It’s hard to get the intonation just right, especially on the first read. Passages written in dialect require a bit of thespian improvisation.

Reading Lab:

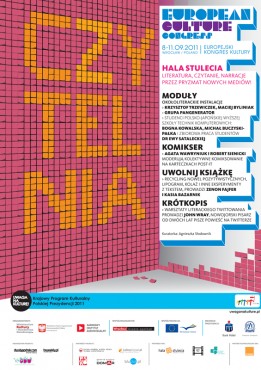

Modules

As part of Modules we will get to experience installations by Krzysztof Trzewiczek, Maciej Byliniak, panGenerator group, students of the Polish-Japanese Institute of Information Technology: Bogna Kowalska, Michał Buczyński-Pałka from the Multimedia Workshop led by Anna Klimczak and Marcin Wichrowski, and a joint project of Ewa Satalecka’s students.

Another web-savvy reader ignores the noise on the internet. He coolly assesses each link. He reads the ledes carefully, examining the source and the name of the author. He isn’t easily ensnared by flashy thumbnails or the primitive animated banners that pop up onto the screen and spill onto the keyboard. He calmly sorts his RSS feeds and organizes his bookmarks. He is fully in control. The sites he visits are meticulously selected. He copies longer pieces into a Word document, where he can pick out any font size he needs. Some novels he listens to in the car.

What about a reviewer? She writes for several magazines. Each article is thoroughly edited before publication. She puts away her first draft for a week before reexamining it with a fresh, critical eye. She proofreads, edits, and sends a polished — yet still raw — version to the editor. The editor writes up a response. The author goes back to the article, making the required changes, discusses the piece with the editor, and sends it back. The editor has some more minor comments. The author responds to them, and the article is sent to the proofreader. The author receives yet another series of questions, to which she responds. The proofreader finishes up the piece. The editors prepare contextual material: short pieces that will run alongside the article. The photo-editor carefully chooses a photographic illustration or counterpoint. The managing editor puts the finishing touches on the piece, adding headings and a lede, and choosing one of the two titles proposed by the author. The only thing she publishes in real time are her status updates.

Reading Lab:

Comixing

Robert Sienicki and Agata Wawryniuk, from the Polish Association of Comics will moderate a session where participants will jointly create a comics on the post-it notes. With the completion of this stage of the project, such created works will be scanned and used as a material for the interactive on-line application. The second stage is to be executed on the Web.

And then there’s the poet.

Is he really a poet? His poems end suddenly, as if incomplete. They are sloppy, disheveled, sewn together with the cheapest thread of advertising slogans, magazine headlines, jingles, text messages, tweets, status updates, bits of emails, and phone calls dropped because the coverage

was bad, his battery died, he was in a hurry, he couldn’t talk, or he was in a meeting.

They are unsophisticated expressions of his

helplessness against the deluge of mediocre and disproportionately reduplicated literary forms.

“I don’t lend out books,” he says: a candid and final refusal. This one is a book lover who is still getting over the post-traumatic stress brought about by his failure to recover a few of his favorite titles.

Runner with e-reader, photo: A. Słodownik There is nothing left to do but flee the scene of the criminal request for a loan and find a less radical owner of an interesting book collection. Readers such as these sign their loot with their first and last names, and run a spreadsheet of loaned and returned books. They send reminders to their borrowers in due time. (“Runners” don’t need to: electronic editions can be borrowed for 14 days, after which the copy expires automatically.) To return a book, you need to set up a meeting: there is a priceless interpersonal aspect to the exchange, and a nightmare to those with anti-social personalities. (Then there are book lovers who won’t borrow books from others. They feel compelled to own their copies, expressing their ownership by highlighting and underlining the pages. They need to see their progress and thus monitor their activity as a reader: a constant struggle in these times of short attention spans.)

Runner with e-reader, photo: A. Słodownik There is nothing left to do but flee the scene of the criminal request for a loan and find a less radical owner of an interesting book collection. Readers such as these sign their loot with their first and last names, and run a spreadsheet of loaned and returned books. They send reminders to their borrowers in due time. (“Runners” don’t need to: electronic editions can be borrowed for 14 days, after which the copy expires automatically.) To return a book, you need to set up a meeting: there is a priceless interpersonal aspect to the exchange, and a nightmare to those with anti-social personalities. (Then there are book lovers who won’t borrow books from others. They feel compelled to own their copies, expressing their ownership by highlighting and underlining the pages. They need to see their progress and thus monitor their activity as a reader: a constant struggle in these times of short attention spans.)

Stories

Stories are also spun in more than one way. Some tell tales the old-fashioned way: set-up, confrontation, resolution. They are like talking Dostoyevskies: they draw on and dig deep.

Reading Lab:

Workshops

Tweet workshops are organised by dwutygodnik.com|biweekly.pl; John Wray, a New York writer and columnist who has been writing a twitter novel for two years, will be the trainer.

Katarzyna Bazarnik and Zenon Fajfer will run a cycle of workshops called Liberate a Book. Its participants, divided into small groups of 16 persons, will practise: writing in others’ words, exercising the lipogram and the emanative text, and recycling of realist short stories from the late 19th century.

They offer details, almost as intricate as the extended descriptive passages of 19th century novels. Any additional side plots seem almost indispensable. The stories are introductions to introductions. The context is fully illustrated before the heart of the matter even appears on the horizon. The climax of the story, when it comes, is long awaited.

Then there are stories that trail off and get tangled up, rush ahead and retreat, and become emotional and anxious. Like that so-called poet. They introduce elements of chaos and allow the reader to piece the story back together in any number of ways. Key details are tossed in with barely-relevant tangents. The entire story is difficult to tie together, to understand the causes and effects, the beginning and end. The tension is high.

The Reading Lab

The Reading Lab at the European Culture Congress is intended to confront these images and pose a variety of questions. Do words really not stand a chance against sixty images per second? (To find out, try the non-video game created by the panGenerator group using an 8-bit Nintendo controller and a thermal printer.)

panGenerator groupWhat forms can Łukasz Orbitowski’s novel Tylko Maks assume? (Aside from the existing ones. And games.) Can the deconstruction of text produce new quality? What will 19th century novels transform into at the hands of the participants of liberature workshops, conducted by Zenon Fajfer and Kasia Bazarnik? (Books might be sacred, but intervention can be a blessing.) How does one read using eyeglasses and fingers? (Students of the New Media Art program at Polish-Japanese Institute of Information Technology decided to find out.) How do we see musical pieces such as Lekcja by Eugeniusz Rudnik (a master of narrative audio-collages at the Polish Radio Experimental Studio)? What about Miron Białoszewki’s Chamowo? What do we need to do to hear his voice extracted from the noise? (I believe it is within our grasp to overcome the amalgamate of voice and text.) How does one write a novel on Twitter? How do John Wray’s characters function in one-sentence chapter (as they have been doing for two years now)? Can a group write a graphic novel by contributing individual panels? (Post-its as comic books.) Can it be done by intertwining parallel plot lines like in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Amores Perros? Should you cut a page if that’s the only way to get at the content?

panGenerator groupWhat forms can Łukasz Orbitowski’s novel Tylko Maks assume? (Aside from the existing ones. And games.) Can the deconstruction of text produce new quality? What will 19th century novels transform into at the hands of the participants of liberature workshops, conducted by Zenon Fajfer and Kasia Bazarnik? (Books might be sacred, but intervention can be a blessing.) How does one read using eyeglasses and fingers? (Students of the New Media Art program at Polish-Japanese Institute of Information Technology decided to find out.) How do we see musical pieces such as Lekcja by Eugeniusz Rudnik (a master of narrative audio-collages at the Polish Radio Experimental Studio)? What about Miron Białoszewki’s Chamowo? What do we need to do to hear his voice extracted from the noise? (I believe it is within our grasp to overcome the amalgamate of voice and text.) How does one write a novel on Twitter? How do John Wray’s characters function in one-sentence chapter (as they have been doing for two years now)? Can a group write a graphic novel by contributing individual panels? (Post-its as comic books.) Can it be done by intertwining parallel plot lines like in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Amores Perros? Should you cut a page if that’s the only way to get at the content?

Cut, write, and read. However it is you do it.

Tags: remix, recycling, processing, narrative, participation, attention, memory, decentralization, distraction, interdisciplinarity, media convergence, interactivity, presence, co-creation, blurring boundaries, culture of abundance, loss, non-reading, typography, liberature, collage, lipogram.

Tags: remix, recycling, processing, narrative, participation, attention, memory, decentralization, distraction, interdisciplinarity, media convergence, interactivity, presence, co-creation, blurring boundaries, culture of abundance, loss, non-reading, typography, liberature, collage, lipogram.

Project partners: Polish-Japanese Institute of Information Technology in Warsaw, lubimyczytac.pl, Domar Interior Gallery, bludot.pl and Polish Association of Comics

European Culture Congress is a part of the National Cultural Programme of the Polish Presidency in the European Union Council.

Organisers: The Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The National Audiovisual Institute

Co-organiser: City of Wrocław Co-funder: European Commission

Patrons of Polish Presidency: PKO Bank Polski, PZU

ECC Partners: Centennial Hall, Feature Films Studios, European Culture Foundation

ECC Technological Partner: Orange