We live in a world mired in a chaotic, aggressive iconosphere, constantly bombarded with visual stimuli; ocularcentrism has dominated modern Western civilization — or so the burgeoning and controversial filed of visual culture (developed elsewhere) would have us believe. The notion of the privileging of the visual in the contemporary world is a truism, which — like all truisms — effectively prevents us from asking: Is this really the case? Is sight — hitherto regarded as the most cognitive and noble of the senses — the main tool facilitating our contact with the world?

Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam,

Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam,

detail from the Sistine Chapel

It is our quotidian experience — rather than the musings of researchers — which shows us that sight is effectively being superseded by an inferior, suspect sense: touch. An impure, corporeal sense with bad associations. And yet it is the sight rather than the touch, the finger rather than the eye, that regulates our participation in the contemporary world. Click, touch, press, hold, hover (with your finger, naturally): commands found in the instruction manuals of all the hardware we can no longer live without. From electrical sockets to laptop keyboards, phones, cell phones, terminals, remote controls, touchscreens, alarms, ATMs, metal detectors, access codes, and bank passwords: all of these are controlled by the touch of the finger. It is the index finger that plays the decisive role. The middle finger is useful as well, unlike the thumb, ring finger, and pinkie, which are of little help when trying to punch in a PIN. When the fingers becomes too clumsy a tool, we must resort to the fingernail.

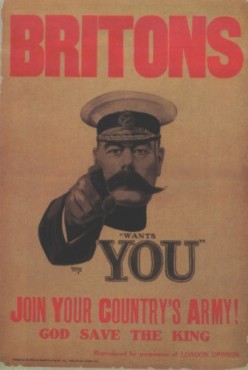

Great Britain propaganda poster, 1914“Using his hypersensitive antennae, Witold Gombrowicz sensed the finger’s demonic nature and our helplessness against the pointed finger”, wrote Jan Gondowicz in his bold essay on the finger and its petrifying touch. Gondowicz reminds us of the evil, magical power of the finger, it deadly force. The finger can be use to point at as well as threaten others. Aimed at the eyes of the viewer, the finger on a 1914 recruiting poster cost 600,000 young Englishmen their lives; the Soviet World War II poster it inspired led to the death of ten times as many Russians. According to traditional beliefs, the finger, just as well as the evil eye, could be used to cast a curse. Do we not find distant echoes of these fears in the parental admonition: “Don’t point your finger!”?

Great Britain propaganda poster, 1914“Using his hypersensitive antennae, Witold Gombrowicz sensed the finger’s demonic nature and our helplessness against the pointed finger”, wrote Jan Gondowicz in his bold essay on the finger and its petrifying touch. Gondowicz reminds us of the evil, magical power of the finger, it deadly force. The finger can be use to point at as well as threaten others. Aimed at the eyes of the viewer, the finger on a 1914 recruiting poster cost 600,000 young Englishmen their lives; the Soviet World War II poster it inspired led to the death of ten times as many Russians. According to traditional beliefs, the finger, just as well as the evil eye, could be used to cast a curse. Do we not find distant echoes of these fears in the parental admonition: “Don’t point your finger!”?

The world’s most famous finger is that of God, extended towards Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in an offering of life. “Michaelangelo, like every Italian, must have been aware of the magical power of the finger”, writes Gondowicz. Electronic devices have unexpectedly given a new meaning and range to the magical power of the finger. The finger — no longer Divine, but merely human — remains a mighty giver of live. What has changed is that the “burst of concentrated energy” jumps not from God to man, but from man to gadget; it flows off the finger and onto a key or screen. It brings enormous power to life: on/off, input, output, deposit, withdrawal, payment, transfer, www, e-mail, contacts, accept, connect, close, OK, like…

The finger is equipped with more than just a prematurely forgotten power. It contains our ID, our most personal code: our fingerprints. Their significance has grown along with the role of the finger, no longer banished to criminal files and police investigations. We consider fingerprint scanners a better alternative to passwords when it comes to securing our data. Only the finger, shielded by its unique papillary ridges, can protect us from a new threat that is very real, even though it seems to have been lifted off the pages of a sci-fi novel: identity theft.

The world is ruled by the finger. Not just the finger hanging over the apocalyptic nuclear launch button. Each of our fingers. Welcome to the era of dactylocentrism.

translated by Arthur Barys