Michał Kmiecik, the rising star of Polish theatre, presents an adaptation of Crime and Punishment as part of the Youth Stage series by Dramatyczny Theatre in Warsaw. This rather peculiar version of the tale does away with linear narration and leaves little more than shreds of the story intact, with characters and scenes taken out of context. Faced with the gravitas of theatre’s social mission, the artists at the Dramatyczny Theatre eventually abandon their intention to stage an adaptation of the Dostoevsky novel. Instead of answering the question, “Who killed Alyona Ivanovna?” – Kmiecik appears to say – theatre should be asking, “Who killed Jola Brzeska?”.

But before we go on to Jolanta Brzeska, a few words about the director and playwright. Michał Kmiecik, aged twenty, is the author of Wedding (Wesele), a semifinalist for the 2011 Gdynia Drama Prize, set in Poland at the height of the government’s war on synthetic drugs, and the anti-corporate The Death of the Employee (Śmierć pracownika), a winner of the “Metaphors of Reality” competition held by Polski Theatre in Poznań. The young Vratislavian has also directed two plays, Until Lions Have their Historians… – staged last June at the Dramatyczny Theatre’s “The Nigger’s Struggle with Europe” festival – and the performance The Guns of Mr Youde. A Good Man from Hubei at the European Culture Congress in Wrocław. Quite an impressive portfolio for a first-year philosophy student! Kmiecik is often labeled as representing the Occupy Wall Street generation or the “at-will employment generation” in Polish theatre. In his view, the theatre isn’t supposed to be a venue for elite entertainment. It’s supposed to make bold, powerful statements about the here and now.

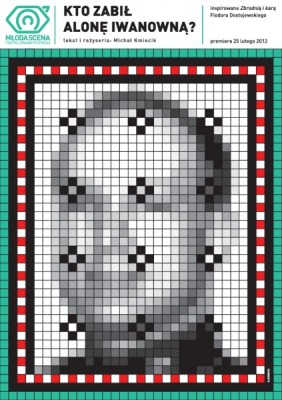

Who Killed Alyona Ivanovna?,

Who Killed Alyona Ivanovna?,

dir. Michał Kmiecik,

Dramatyczny Theatre in Warsaw,

premiered on 25 February 2012His latest piece at the Dramatyczny Theatre is brief, witty, hilarious, well-paced, and fun to watch, though it’s easy to get lost in the whirlwind of the quotes and cultural (and pop-cultural) references. But the messages is clear, and Kmiecik’s style is unpretentious. We learn that the actors are working on an adaptation of Crime and Punishment. Someone tells Dostoevsky’s biography (referring to him as “that Russki”) and explains the meaning of katorga (“hard work for little pay”). But it quickly turns out that Raskolnikov has other problems (he has to earn a living and has no intention of killing anyone), which raises the question of who is going to have to kill Alyona Ivanovna. Małgorzata Maślanka, in the role of Ivanovna, paces across the stage with an axe as she waits for her murderer, while an endless series of candidates pass through. Among them is Marmeladov (Piotr Siwkiewicz), who complains of the humiliations “that Russki” has made him suffer (pimping his daughter, among others). Then there’s Anders Breivik, the homicidal madman from Utoya island (the poster bearing his likeness sparked protest from the Norwegian Embassy, as if upon the director’s request) along with Lars von Trier, who admits to his fascination with Hitler in a bold scene performed by Dariusz Niebudek. Other appearances include one by Marek M. (Waldemar Barwiński), the Warsaw property litigation attorney who rose to infamy by reclaiming houses from the city on behalf their pre-World War II owners, buying up claims, and brutally evicting tenants, all in the name of restoring the city’s “former charm”, only to tear down the reclaimed properties to make room for shiny glass skyscrapers.

Alyona Ivanovna’s dreams are finally fulfilled by Uncle Vanya, played by Krzysztof Ogłoza, who takes out the frustration of his failed life (and particularly his inept attempt to kill Serebryakov). He achieves a one hundred percent success rate this time around, killing every last character in the finale. There are also references to von Trier’s Melancholia, the death of Amy Winehouse, and the recent occupation of the Prasowy milk bar in Warsaw (a protest against closing cheap restaurants to replace them with exclusive services – ed.) – all of them events that strongly define our here and now in a variety of dimensions.

The actors reveal glimpses of their private lives, discussing their incomes and everyday problems. They tend to speak to the audience rather than to each other, like in a Frank Castorf play, interrupting and disrupting each other’s parts in attempts to win our attention. All of this is very Brechtian (this intentional affinity, like Kmiecik’s other inspirations, is revealed in the script, which references the Volksbühne’s performances of two Brecht pieces at the Dramatyczny last June). Associations with the Demirski-Strzępka duo are particularly clear as well. Kmiecik quotes his mentors verbatim, applying their forms like ready-mades.

The tone of the piece takes a sudden serious turn with the mention of Jolanta Brzeska, a tenants’ rights activist who lived in one of the buildings reclaimed by Marek M. Brzeska died in unexplained circumstances last year. Her burnt body was found in the Kabaty forest, and it has not yet been determined whether her death was the result of self-immolation or a lynching by her creditors. Nonetheless, her spectacular death lent momentum to the tenants’ rights movement, which took her as its patron and holy martyr. Following the premiere of the play, an audience member wearing a hooded sweatshirt and a Guy Fawkes mask – a symbol used by Anonymous – climbed onto the stage to announce the tenants’ rights movement’s planned commemoration of the first anniversary of the death of Jolanta Brzeska. It is unclear whether the girl’s announcement was the last scene of the play, or just an early result of its social resonance. Regardless, Kmiecik must be pleased with the conclusion, which proved that theatre is – or may be – an important venue for social debate.

I have only one doubt: if the Demirski-Strzępka style of communicating with the audience is canonised, will that not kill its authenticity? Like any outstanding student, Kmiecik will have no choice but to abandon his teachers.

translated by Arthur Barys