It doesn’t start like an opera. The curtains are left open, revealing the stage. On it a giant column hall in dark wood has been erected, with floodlights on the ceiling and enormous windows in the side walls, refracting the light like stained glass panes in a church. But this is no church: it’s a lecture hall with even rows of desks and typewriters facing a lectern with a microphone. In the back and off to the side are rows of ornate glass doors. In the pit, the 30-piece Klangforum Wien orchestra waits for the conductor to emerge.

Students – boys and girls – come out, all similarly dressed (gray sweaters, white shirts, ties, eyeglasses). Next comes Seneca (played by the British Jamaican actor Willard White), their lecturer, pacing slowly and solemnly, wearing a purple professor’s gown under his jacket and carrying a briefcase and a few books. He stands before the microphone and begins the class: a brief lecture (excerpts from Wittgenstein and Foucault) and discussion. In English.

Poppea e Nerone

Claudio Monteverdi / Philippe Boesmans Poppea e Nerone premiered 12 June 2012 in Teatro Real in Madrid.

Conductor: Sylvain Cambreling,

Director: Krzysztof Warlikowski.

He asks questions; some of the students speak on their own initiative. There’s Nerone, Poppea, Ottavia, Ottone, Drusilla… All of them young, bursting with energy and unconcealed interest. The sit at their desks facing the audience; he stands with his back turned, but we see his face projected onto the rear wall. He is focused, imperious, and confident, but his words and thoughts suddenly provoke doubt in his mind; he raises his voice, visibly upset. He talks about fear as the fundamental element of life, about the lust and love he has never experienced, kept away from them by the philosophy he expounds. He falls silent for a moment, apologises to the students, and ends the lecture. The students applaud and exit the hall.

The cleaning ladies enter the hall, pulling a cart and supplies. Seneca falls to the ground. A figure appears on the left, by the sink: a black man, much younger than him, dressed in a similar purple robe. Is it Seneca in his youth? Or perhaps an unfulfilled projection of himself? The cleaning ladies in the back take off their smocks, revealing themselves to be Virtue (Lyubov Petrova), Fortuna (Elena Tsallagova) and Amore (Serge Kakudji), dressed in swimsuits and draped in pageant sashes, each the winner in a separate category. There are no more gods in this world, only delusions.

The modern goddesses kiss the young Seneca and begin singing Monteverdian melodies in Boesmansian harmonies (Sylvain Cambreling appeared on stage to no applause; the music came in just as unexpectedly). Amore then proposes a test, to be conducted on a person. The elder Seneca still lies on the ground, his arms outstretched, asking for help. The music of the prologue falls silent as the goddesses revert to their roles as cleaning ladies. They run up to the man on the floor, talking amongst themselves in Russian. They lift him up, give him water, and help him leave. The words “six years later” appear on the backdrop. The opening act of the opera begins, with Nerone ruling the world, surrounded by dark-haired young men in eyeglasses, button-down shirts, knee socks and shorts, like members of Mussolini’s brigades or the SS (the Spanish Falange wore navy blue shirts).

Monteverdi wrote L’incoronazione di Poppea to the libretto by the Venetian lawyer Giovanni Franscesco Busunello in 1642, at the age of 72. Elderly and experienced, Monteverdi gave us a bitter story of blind lust that leads to happiness in the end, but not before hurting many along the way. A revolution at the time, the opera tells the story of actual historical figures rather than mythological heroes. We see bloody events take place on stage, with Nerone and Poppea – two of the darkest characters of Roman antiquity – in the leading roles. Audiences should keep in mind the true end of that relationship; they will then understand the bitterness behind the sweetness of the romantic “Pur ti miro, pur ti godo” (I adore you, I desire you – ed.) duet.

The premieres in Venice (in the 1643 carnival season) and Naples (1651) brought only brief success. What’s interesting is that the operas were never published in print. The existing Venetian and Neapolitan manuscripts diverge significantly; some musicologists even argue that the piece is a collective work merely bearing Monteverdi’s seal of approval.

The Belgian composer Philippe Boesmans (born 1936, author of a 2009 opera based on Gombrowicz’s Yvonne, princesse de Bourgogne that has not yet been performed in Poland) first orchestrated Monteverdi’s score in 1989 for the La Monnaie in Brussels, then under the leadership of the Frenchman Gerard Mortier, who has for two years been the artistic director of Teatro Real in Madrid, following his success at directing the Salzburg Festival and Paris Opera. It was he who opened the grand opera stage to Krzysztof Warlikowski six years ago (starting with Iphigénie en Tauride, then The Makropoulos Affair, Parsifal, and finally King Roger). He continues this collaboration in Madrid, hosting the Parisian production of the Szymanowski opera and entrusting the Polish director with creating a new version of Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea with Boesman’s arrangement.

The sound of Poppea is subtle and airy; thanks to the perfection of Sylvain Cambreling and Klangforum Wien, the piece is like a fine cobweb with drops of water suspended in it: easily destroyed unless treated with the utmost care. Though he retains that which was left by Monteverdi – the melody and the basso continuo parts – Boesmans creates a code of his own, associating particular instruments and sounds with individual roles, giving them character and boldness. The music plays heavily on the Baroque, understandably, and there are plenty of accents and details that are blurred and obscured in the performance, though I can’t imagine it being otherwise. The theatre seeks to touch the emotion in music, not its intertextuality. It leaves intertextuality to the trained ear of the expert, choosing instead the role of the observer, the witness to history, the storyteller, and, finally, the historiosopher.

Warlikowski sets the opera in the 1930s, on the eve of the birth of 20th century totalitarianisms (the first scene is accompanied by footage of the 1936 Olympic parade in Berlin), but he makes no attempt to seek out their roots, coolly observing their development from one stage to the next, instead. He places cameras on stage and headphones on the ears of the men; we’re constantly being teleported to the present day, in keeping with the motto published in the program and projected on stage – a quote from Einstein that explains how the past, the present and the future are merely illusions, and how time, which is more than it seems to be, doesn’t flow in just one direction. And it’s not about any particular model or system: Nazism, Italian Fascism or Francoism. All of the above are reflected in the nameless cohort that accompanies Nerone.

As they exercise and dance in slow motion, incessantly observing everything and everyone, these men undergo collective transformations. They appear at the beginning of the first act, dressed in black uniforms (shorts, knee socks, shirts and ties, eyeglasses, haircuts), then return with lighter hair (like Nerone), and finally reappear with shaved heads, tall boots and leather gloves. They are indiscernible, disturbing, threatening, willing to follow orders, silent and powerful in numbers, like all communities associated with ideological movements. It is an extraordinarily powerful theme, one that exists completely outside the music and stems from the perspective assumed by the director.

Warlikowski’s readings and interpretations are always his own. He seeks out crevices in the opera and peers into them. He unravels series of events into their minute components, layering his own obsessions and anxieties on top. But none of this is silencing or soothing – the purpose, indeed, is quite the opposite.

It is the juxtaposition of one’s thoughts with the narrative – itself often hidden – that produces the scene or image; it happens instinctively, emerging from the chaos that bubbles up and releases new energy. Add to that music and song, and a new world is born out of counteraction, contradiction, disruption, and completion. It once seemed to me that Krzysztof Warlikowski didn’t direct the music and the opera as much as he did his own internal story, in which the music was superfluous, much like light and space. Perhaps I was mistaken, or maybe something has changed. Today, Warlikowski appears to be listening to the music carefully, in all its contradictions and grandeur, even if he did start with Monteverdi’s score, only to be surprised by Boesmans’ orchestration, airy and clear, devoid of that Baroque drive and lacking in explosions and crescendos.

The director has taken this world created by Busenello and Monteverdi, and later by Boesmans, and selected the themes he found most interesting. He places Seneca in the center of the story. The context of his philosophy and suicide becomes one of the leading motifs of the performance. Seneca, who espouses a belief in restraining emotion and eliminating feelings, can only lose the confrontation with Nerone and Poppea’s world of lust. Willard White’s acting reveals deep tensions between the stoic calm that stems from Seneca’s principles, and the emotions he experiences in various situations. The historical Seneca, a tutor to Nero, was forced by his former pupil to commit suicide. Meanwhile, the operatic Seneca doesn’t accept death as much as he chooses it himself; it is the only way for him to achieve peace and happiness. In one ingenious scene, Seneca sits down to say goodbye to his fellow lecturers with a bottle of whisky. Warlikowski’s “Non morir, Seneca, no!” breaks down the pain of anticipation with laughter. There’s an ironic chuckle in the scene, and a sense of preparation for the end. Left alone, Seneca sets up a camera (the projection on the backdrop intensifies the drama of the situation), sits down in an office chair, slits the veins in both his wrists with a quick gesture, and rolls off to the back of the stage, pushing the chair with his feet.

Warlikowski has created a phenomenal gallery of characters, unhappy from birth till death, nursing their own misery and pain. Only the music that comes from their bodies offers any proof of the beauty they are capable of making. Each of them has their own grief to parade around, and their own loneliness that they only appear to want to escape.

Even the minor characters have their minute in the spotlight. There’s the Nurse (Jadwiga Rappé), who resembles a cross between Cruella de Vil and Limahl, and who performs an extraordinarily bitter aria in the second act about her wasted femininity. Rappé paces about the stage holding a cup of coffee in her hands and a cigarette in her mouth. As she sings, she sits down on the desk, stretches out her weary, stocking-clad legs, and puts her feet up on the chair, wiggling her toes to relax. She recalls her bygone youth with melancholy in her voice.

Then there’s Arnalta (a female role sung in this production by tenor José Manuel Zapata), who seeks happiness and her/his own identity. When he appears for the first time, he looks more like Poppea’s stylist (or perhaps her hairdresser), helping to transform her into a goddess. There’s also Ottone (counter-tenor William Towers), Poppea’s rejected husband, whom she cuckolds before his own eyes; a soft and weak man who resorts to violence (holding a knife to her neck) to force her to return, begs for intercourse, and masturbates at the very thought of her, writhing in pain (act one, scene one). Ottavia (Maria Riccarda Wesseling), ill with loneliness and desperate for intimacy and sex, masturbates on a chair, holding a pillow under her black dress to simulate pregnancy. Her demise is painfully silent. Six men in white t-shirts and shorts are rowing. She stands between them, next to a chair, and sadly sings the farewell “A Dio, Roma”. A couple of thugs come in, dressed in black, their heads shaved. One of them picks her up and leaves. Ottavia struggles to free herself, as if wishing to walk the final path to her death on her own two feet.

And, finally, the titular pair: Poppea (Nadja Michael) and Nerone (Charles Chastronovo). In the duet in the first act, the two crawl on the ground on their backs, like worms or children at play. She in a white t-shirt and blue panties, he in white boxer shorts, an unbuttoned black shirt, and his pants around his knees. Both have short blond hair; his is slicked back, hers is combed over to the side, although she’ll soon don a Marylin Monroe-style wig and a silver dress. A phenomenal woman, for whom the man/ruler loses his head; a phenomenal actress, for whom there are no protective barriers or taboos on stage.

Their relationship – at least as portrayed by Warlikowski – is a mixture of blind lust and methodical humiliation. They play the torturer and the victim, with both roles in constant flux. In another scene, in which Nerone attempts to force Seneca to allow him leave Ottavia and marry Poppea, we see him dressed in a black suit and dark shirt with white dots. Around his neck is a tiny pacifier, which he occasionally sucks for fun. Soon after, he gets into a fight with his lover and brutally forces the toy into her mouth, provoking a bout of coughing.

The death of Seneca brings transgression. On the left appears the philosopher’s dead body, stretched out on an autopsy table. Nerone (barefoot in a long silver dress, with a blue peacock scarf in his hand) and Lukan (in a white t-shirt and underwear, red stockings and golden heels) sing a joyful song to the camera, smearing the dead man’s blood on their lips.

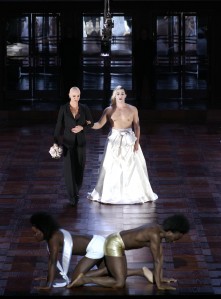

In the penultimate duet Poppea (wearing a long red dress) lets herself be abused by Nerone (clad in black, like his thugs), before ordering him to lie at her feet, crushing her heel into his body. And finally comes the finale. Six rowers lie on their backs, as if dead. In the middle, two men form a bench. Poppea, head shaved, wears a black men’s suit; beside her Nerone, his chest exposed, wears an ornamented white dress, his hair half male, half female, in the style of Marylin Manson. The walk calmly and cheerlessly, singing one of the most beautiful Baroque love duets. They sit on the benches. The music ends. Silence. The epilogue is projected onto the backdrop, briefly telling the stories of each character’s sad demise. Poppea dies a few years later, kicked by Nerone while pregnant. The silence is heavy and unbearable. It’s no longer melancholy, it’s fear. Fear of man.

translation by Arthur Barys